As feats of worldbuilding go, it is hard to go past Tolkien’s Legendarium as the chief and foremost example of the craft. Even those who have a passing familiarity with his writings know that Tolkien spent years developing languages, cultures, genealogies, calendars, histories, life-cycles, and so much more. From the Appendices to The Lord of the Rings to Laws and Customs of the Eldar or The Shibboleth of Fëanor, there is a dearth of information concerning nearly any question one might have (and many one does not!) concerning Tolkien’s beloved Middle-earth.

Yet, even in so meticulous a sub-creation, mysteries and problems remain. Of course, many decent Legendarium lovers will be quick to tell you that the greatest enigma in Tolkien’s writings is Tom Bombadil. There are a few other contenders for the crown – Ungoliant’s origin, perhaps, the fate of the Entwives, the nature of the Orcs. But I think that few would name a character from The Hobbit as being Tolkien’s greatest enigma, though, which is a great pity. Because, when you really think about it, just what is up with Beorn? Who is he, what is he, even why is he?

We are told a little about Beorn in The Hobbit, mind. Indeed, almost everything we know about him comes from a single expositional speech from Gandalf to Bilbo, as the two approach his strange house:

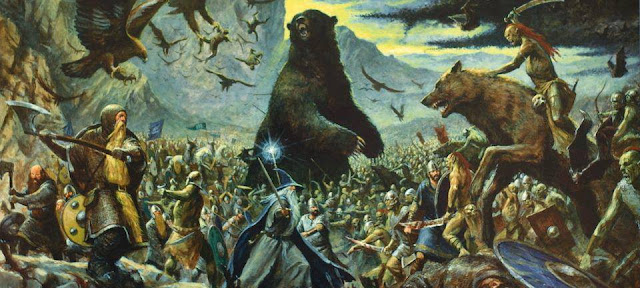

“He is a skin-changer. He changes his skin: sometimes he is a huge black bear, sometimes he is a great strong black-haired man with huge arms and a great beard. I cannot tell you much more, though that ought to be enough. Some say that he is a bear descended from the great and ancient bears of the mountains that lived there before the giants came. Others say that he is a man descended from the first men who lived before Smaug or the other dragons came into this part of the world, and before the goblins came into the hills out of the North. I cannot say, though I fancy the last is the true tale. He is not the sort of person to ask questions of.”

“At any rate he is under no enchantment but his own. He lives in an oak-wood and has a great wooden house; and as a man he keeps cattle and horses which are nearly as marvellous as himself. They work for him and talk to him. He does not eat them; neither does he hunt or eat wild animals. He keeps hives and hives of great fierce bees, and lives most on cream and honey. As a bear he ranges far and wide. I once saw him sitting all alone on the top of the Carrock at night watching the moon sinking towards the Misty Mountains, and I heard him growl in the tongue of bears: ‘The day will come when they will perish and I shall go back!’ That is why I believe he once came from the mountains himself.”

The Hobbit, Chapter VII, ‘Queer Lodgings’, by J.R.R. Tolkien

It is not much to go on, to be honest. Indeed, the number of things that Gandalf does not know and merely guesses would seem to outnumber the things Gandalf does know, including the very pertinent question as to whether Beorn is a bearish man, or a mannish bear. We also do not learn much about the nature of this ‘skin-changing’, including how or why it works. We don’t even really learn that much about Beorn’s bond with his animals – is he able to speak with all animals? Or simply those he has taken under his care?

We learn a little more about Beorn as the book progresses, including his likes and dislikes (he dislikes dwarves, and really dislikes goblins, he thinks Radagast is ‘not a bad fellow as wizards go,’ but has never heard of Gandalf, he does not care much for jewels and crafts of metal, but he is a fierce and loyal friend to those who have earned it, and he has something of a sense of humour). Finally, towards the end of The Hobbit, we get this little piece of information concerning Beorn’s further history.

Beorn indeed became a great chief afterwards in those regions and ruled a wide land between the mountains and the wood; and it is said that for many generations the men of his line had the power of taking bear’s shape, and some were grim men and bad, but most were in heart like Beorn, if less in size and strength.

The Hobbit, Chapter XVIII, ‘The Return Journey’

So, this skin-changing gift or skill of Beorn’s is at least not unique to him – but even then, whether it is a power passed through blood or learnt (or some measure of both) is not described.

In short, The Hobbit reveals very, very little about Beorn, about his origins or his nature. This, though, is perhaps not a surprise – after all, The Hobbit also drops tantalising tidbits of information about places called Gondolin, about wars between Goblins and Dwarves, about councils of wizards that are opposed to some vague Necromancer. It is then the duty of a good and enthusiastic Tolkien scholar to delve deeper into Tolkien’s writings and to find how these pieces link up. Gondolin, of course, is one of the greatest Elvish cities, and is dealt with at length in The Silmarillion. The bitter wars between the Dwarves and the Orcs are elaborated upon at length in the Appendices to LOTR. And, speaking of LOTR, that pesky Necromancer pops up again there, and the movements of the White Council are also described in the Appendices and in other, posthumously published texts of Tolkien’s. The Hobbit is, in short, rife with these little mysteries and fleeting mentions of a wider world – these ‘textual ruins’, to borrow a wonderfully evocative phrase from Michael Drout.

So, what of Beorn? What do we learn of him and his kind from exploring Tolkien’s wider writings? The answer is…pretty much nothing.

We learn a little of his people and their lands in LOTR, when Frodo speaks with Gloin about how they keep the mountain passes open for travellers. Later, Frodo sees the lands of the Beornings beset by war, as he sits on the high seat at Amon Hen. The Appendices tell us that the Beornings were closely related to the Men of Éothéod, who became the Rohirrim, and that after the fall of Dol Guldur and the end of the War of the Ring, much of Mirkwood was given over to them. Further, it is possible that the Beornings aided Aragorn in his hunt for Gollum, as described in earlier drafts of LOTR (but this reference was abandoned, or at the least edited out, by the time of publication).

But all of this is political, cultural, social information, and does not shed one bit of light upon the central problem of Beorn and his folk. How, and why, are they able to change into bears? By what means are these Men able to use such an explicit and clear supernatural power, especially in a world where magic is generally treated as something vague and spiritual, and those who call upon it are explicitly Other in some way? This is no Harry Potter, where one can read a book and learn shapeshifting with relative ease. So, how come Beorn can do what Beorn does?

There is, as far as I can tell, no answer, nor even a hint of an answer, in all Tolkien’s writings. Never once did he try to explain it, never once did he grapple with it. In this sense, the mystery of Beorn and his nature is actually much more profound than the mystery surrounding the origin of the Orcs. For in the case of the latter, Tolkien did try to explain it, and never seems to have come to an answer that was satisfying to him. The problem of the Orcs is not in finding an answer, but in debating and choosing an answer that fits – and, as I have said before, it’s ultimately a choice I’m not terribly interested in making (though the debate remains very worthy!). Beorn’s nature, though, is completely unknown, because Tolkien never really dealt with it.

Indeed, this even separates Beorn from our opening enigma, Tom Bombadil, as Tolkien did describe a little of what Bombadil is and isn’t in various letters. Further, on a cosmological scale, it is plausible to come up with an explanation for Bombadil, as some Maia, a genius loci attached to the Old Forest and its borders. Beorn, again, defies such neat categorisation. It seems likely, almost certain, that Gandalf’s instinct is correct, and that Beorn is, first and foremost, a Man. But beyond that, we know nothing about him.

At this point, there would seem to be two possible directions for this essay – to wind up into a fairly unsatisfying ‘that’s all, folks!’, or to start on some wild metaphysical speculation. I intend to do neither. Rather, I’m interested in a further question – why is it that, in all of Tolkien’s extended writings, there is no further discussion of Beorn?

The easy and quick answer is that it is because Beorn, as with the entire The Hobbit, doesn’t really ‘belong’ to the Legendarium. He is, along with the entire story, a graft, an extraneous addition to Tolkien’s mythology of Elves and Valar, mortality and creation. It is well known that The Hobbit began as a children’s story, with its simple passing links to the Legendarium included more for Tolkien’s private amusement than out of any real desire to make Bilbo part of the same world that Beren and Fingolfin lived in, and that it was only later that Tolkien decided to fully integrate this innocent fairy tale into his wider world. Hence, the lack of information about Beorn is a symptom of The Hobbit’s tenuous place in the Legendarium. If this children’s story doesn’t really ‘fit’, then neither does Beorn.

I have an alternative explanation, though, and one with (I hope) some little basis in the text. In the Prologue to LOTR, we are told this about the origins of Hobbits:

The beginning of Hobbits lies far back in the Elder Days that are now lost and forgotten. Only the Elves still preserve any records of that vanished time, and their traditions are concerned almost entirely with their own history, in which Men appear seldom and Hobbits are not mentioned at all. Yet it is clear that Hobbits had, in fact, lived quietly in Middle-earth for many long years before other folk became even aware of them. And the world being after all full of strange creatures beyond count, these little people seemed of very little importance.

The Lord of the Rings, Prologue, ‘1 – Concerning Hobbits’, by J.R.R. Tolkien

Only the Elves…and their traditions are concerned almost entirely with their own history. This, to me, is terribly important. Because Tolkien’s Legendarium writings were, from the early days of The Book of Lost Tales, meant to be read within a frame narrative. We have, of course, discussed this frame narrative before and how it colours The Hobbit and LOTR. But it is applicable to most of Tolkien’s Legendarium writings, with the possible exception of the various ‘schemes’, drafts that he set down to figure out broad details, timelines, and so forth. However, most of these other Legendarium writings are not written by Hobbits, but by the Elves – or, in some cases, are Elvish tales set down by Mannish (or Hobbitish) scribes.

Nowhere is this more apparent than in The Silmarillion itself, where Tolkien retells LOTR from a rather more…removed…point of view. Here, a story that fills over a thousand pages, is dealt with in a few paragraphs. Of the Fellowship, only Frodo, Aragorn and Mithrandir are named (with the briefest of acknowledgements paid to the ‘servant’ of Frodo who accompanied him). This great tale, this War of the Ring and the Quest of the Fellowship, is a footnote in the histories of the Elves, of chief interest to them because it brought about the defeat of Morgoth’s lieutenant and the end of the Elvish Rings of Power.

It is a thought experiment sometimes conducted to imagine reading The Hobbit and LOTR as they were originally published, without any chance of knowing more about Gondolin or Oromë beyond the glimpses afforded in the text. But I think it’s also a useful experiment to consider the Legendarium from the opposite perspective, from the view of the Elves. In their histories, hundreds of years pass in the blink of an eye. Generations of Men rise and wither without mention, and those few Men who are described are chiefly of interest because their actions affect the Elves and their history. Had Beren desired a mortal maiden, had Túrin’s deeds led to the sack of a Mannish city, you can be sure they would have been afforded no space in the tales of the Elves.

So far, so good. But I think we can extend this experiment a little further. See, there are indeed some scattered mentions of the Beorning-people in LOTR and in drafts of LOTR. But it is only in The Hobbit that we learn anything at all about Beorn’s skin-changing. Or, to put it another way, perhaps in a more academic way, the only reason that we know of Beorn’s strange gift is because Bilbo happened to meet Beorn, and to chronicle it. We can approach this both ways – Bilbo does not mention Gondor, or Ents, or Morgoth, in The Hobbit because he does not go to Gondor, or meet any Ents, or hear tales of Morgoth. But he does meet Beorn. And, as such, Bilbo writes about Beorn.

And Beorn is not the only strange character Bilbo meets (though I do believe he may be the strangest). Bilbo meets ravens that speak the Common Tongue, and a man who can speak to birds in their own language. He tries to steal a talking purse, and listens to the speech of spiders. All of these are elaborated upon little, if at all, in the wider Legendarium writings. Even Gollum, of whom we know so much, is an enigma in The Hobbit – a creature not of orc kind, yet of evil will, with a powerful ring. Were it not for the terrible importance of Gollum in LOTR, we would know nothing more of him either, he would be nothing more than another of the strange beings that Bilbo chanced across in his travels.

The Hobbit is full of such enigmas and curiosities, some explained in supplementary material (mainly those that bear upon the Elves in some way), and many not. So, too, is LOTR, though in the case of that tale, many more of those mysteries are expanded upon by Tolkien, if not wholly explained. There is, in fact, one particularly informative mystery from LOTR that Tolkien dealt with a little – the fate of the Entwives. In Letter 338 of the Letters, Tolkien says, quite plainly, in ‘answer’ to the question of whether the Ents ever found the Entwives again: ‘As for the Entwives: I do not know.’ Not, ‘I have not decided,’ or, ‘I have not come to a satisfying answer.’ I do not know. When approaching the Legendarium as being the creation of Tolkien, this is a baffling answer. He was the primary and sole architect of everything within the Legendarium – how can he not know something about it?

But when Tolkien is considered as the primary translator of, the primary scholar of, the Legendarium, the answer makes perfect sense. Tolkien has, in all his work upon these ancient and fictional texts, never found a source which definitively answers what the fate of the Entwives was. This is not to say there is no answer, or even that he would never have found an answer. But he did not, and that seems to have been satisfying to him.

What we can then extend from that, though, is that had Bilbo happened to meet some Entwives in his travels (or, if one is less optimistic about them, if he had chanced upon their final remains), then Tolkien would have faithfully translated and recorded this. But, of course, Bilbo did not, but he did happen to meet a large man who could turn into a bear. And so we, the readers of these ancient histories, know that a Beorn lived, and had this strange power. But we only know this because Gandalf took Bilbo to Beorn’s house, because Bilbo wrote about the event, and because Tolkien read and translated Bilbo’s writings. Had any of these things not happened, we would not know about Beorn. And this, of course, is true of real-world histories also. There are thousands, millions of people who have lived, achieved great things in their own ways, and died, of whom we know nothing. This does not make them less real than those handfuls of names that history does record, merely less known.

And so, we slowly approach the crux of this essay. I think that, as lovers of Tolkien, there is often a temptation among us to over-categorise, to say that such-and-such belongs to this class of being, or to say that because something does not appear in Tolkien’s Legendarium, it does not exist in the Legendarium either. But I do not think that this is an overly helpful view of the Legendarium, nor, perhaps, even of Tolkien’s intent in creating it.

We often consider Tolkien to have been the first modern ‘worldbuilder’, a craftsman who near-meticulously forged an entire fictional universe of his own. But I think to do so misses something of Tolkien’s own view of his worldbuilding, his own aim in drawing this mythology. Tolkien wished to make a consistent and rigorous mythology, a mythology that would successfully transport its readers into a Secondary World. But that is not to say that he wanted to ‘complete’ it, either, that he had some vision of every last detail of every smallest moment. Indeed, the famed (and currently hotly relevant) ‘other hands and minds’ quote of Tolkien would, at least, seem to support such a view of the Legendarium.

All of this is to say, the Legendarium is indeed a wonderful piece of world-building. But I think that too often, fans and scholars alike are swift to look to Tolkien as being a final answer to questions concerning Arda. It may seem a needless and trivial and even silly wish, but I wish that, rather than people saying, ‘Tolkien did not include this in his Legendarium, and therefore it does not exist in the Legendarium,’ the answer to such questions would be, ‘Tolkien did not write about this in the Legendarium, so we do not know for sure if it existed in the Legendarium.’ It is probably a meaningless distinction, but I think it is a better-informed distinction also.

To the literary scholar, Beorn is able to change into a bear because Tolkien wrote it so. If Tolkien did not write something, then it does not belong in Tolkien’s world. But in my mind, Beorn always existed in the Legendarium, skin-changing and all. We happen to know that Beorn lived and possessed strange powers because Bilbo, chronicler and scholar, stumbled upon him and befriended him. But Beorn’s existence is not contingent upon Bilbo’s either, only our knowledge of Beorn.

And if we only know about Beorn because of Bilbo, just imagine all the things that Bilbo never saw. All the things that Frodo and Sam never came across, and all the things that the Elves may well have met with and simply failed to record. In the Prologue to LOTR, as quoted above, we are told that Middle-earth was ‘…full of strange creatures beyond count.’ As Tolkien scholars, I think we try to count those strange creatures too often. I think there is much more room than we are sometimes willing to grant for strange creatures and events to lurk at the edge of sight.

To be clear, I am not advocating an ‘anything goes’ or a kitchen sink style of world-building to the Legendarium. Tolkien wrote much about what is and isn’t possible, about what types of creatures and things and magicks populate the world and how they all build the world into a consistent whole. But consistency is not the same as completeness, either. Our view of the Legendarium is a frightfully narrow one, informed chiefly by the chronicles of Elves (who were demonstrably not at all interested in Beorn) and a couple of intrepid Hobbits (who were only interested in Beorn because they happened to meet Beorn). And every time we try to ‘count its strange creatures,’ I think we make it a little smaller, a little less wondrous.

There is, of course, no chance of ‘truly’ adding anything, not a single character, city, or race, to Tolkien’s Legendarium, and I do not think we need to. But characters like Beorn are a reminder that Middle-earth is a vast and bewildering realm of Faerie, barely explored. And that, to me, is a large part of the appeal, that there is so much we do not know about Arda, so much left unseen. To some, it is an irritation that we know so little of the origins and nature of Beorn, of Ungoliant, of old Bombadil. But to me, that is part of the beauty and the reality of the Legendarium.

Is not Middle-earth bigger, more compelling, more exciting and mysterious, when we imagine not only the things that we know we do not know, but the things that we do not know that we do not know? And, to me, The Hobbit is the perfect tease of such things, a fleeting glimpse by a single, little and sheltered person, into a world far bigger and far stranger than we will ever know.

Beorn is not some isolated mystery, an unfinished appendage. He is just a mystery that we know a little bit about, a glimpse into a more massive and stranger world than we can conceive. Like I have tried to say, I am not suggesting that we add to Tolkien’s Legendarium, it does not need it. But I do not think we should be afraid to imagine that it is far, far larger and weirder than we know, either. And I think Tolkien would rather like that.

There are more things in heaven and Middle-earth, fans (or at least, self-styled ‘purists’), than are dreamt of in your philosophy.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Thanks for reading – feel free to check out anything else you may be interested in on the blog, there’s plenty more to discover! Follow me on Facebook and on Twitter to stay up to date with The Blog of Mazarbul, and if you want to join in the discussion, write a comment below or send an email. Finally, if you really enjoyed the post above, you can support the blog via Paypal, and keep The Blog of Mazarbul running. Thanks for reading, and may your beards never grow thin!