Once, there was a terrible and wicked monster, who destroyed a great and peaceful kingdom, killing many and driving the survivors into a long and bitter exile. One of those survivors was the prince, then but a youth, who took leadership of his people upon his shoulders after the deaths of his father and grandfather. Through wearisome years, that prince grew as a leader, as a warrior, and as a lord, winning renown for his deeds on the battlefield, and against all odds, restoring his people to a fraction of their former glory despite their homelessness. Yet ever did he dream of vengeance upon the evil creature that had ruined his kingdom, and as he grew and became proud and confident and determined, he resolved to visit doom upon the monster and to reclaim the inheritance that was his by right.

So it was that this banished noble prince assembled a band of his closest companions and, with the counsel of a mysterious old wanderer, set out on a great journey, knowing full well that his death may well lie at the end of it, and yet determined to have his chance at revenge upon the monster, the chance to restore his people and his birthright.

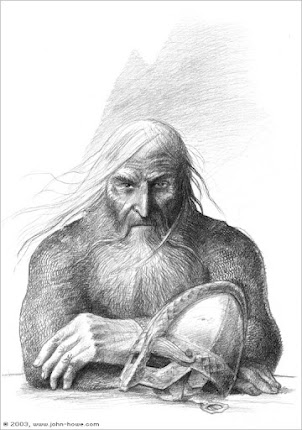

Thorin Oakenshield, my dear readers, should be the chief hero of The Hobbit, by every right imaginable, and according to every narrative standard. It is his quest, his people, his idea to embark upon it. Throughout, he shows himself to be brave and intelligent, matching wits with some adversaries and crossing blades with others. Thorin ought to be the hero, the central figure, as he would have been in any self-respecting Nordic or Germanic tale.

Yet the book is, of course, not called Thorin Oakenshield. We may doubt Bilbo’s wits, courage, physical prowess, or good sense throughout much of the story, but we never doubt that he is the protagonist, which is fairly extraordinary when you think about it. I think that may be partly helped by the fact that the narrator is squarely on Bilbo’s side – not blind to his faults (and sometimes amusingly critical of them!), but also always good-natured and understanding, inviting the reader to place themselves in Bilbo’s shoes. An amusing detail, of course, given that in the fictional meta-narrative of The Hobbit, the book (and therefore narration) is written by Bilbo himself, but there you have it. The end result is that Bilbo is, fully and clearly, the hero and chief character of the tale, and the narrative of The Hobbit makes that very clear through a myriad of techniques.

Anyway, we haven’t quite waffled to the point of this post yet. Thorin fits the model of a conventional hero, while Bilbo is the real unlikely hero, which is likely not news to many readers. But what I realised recently, and what is quite interesting to me about Thorin’s character (and what is possibly terribly obvious) is that I think Thorin is actually keenly aware of this, and that Bilbo’s inadvertent usurping of Thorin’s narrative role informs much of the tension between these two characters.

Some analyses of Thorin as a character focus (I think) overly much on his greed, as it is an easy starting point for discussing him. And to be clear, Thorin is definitely occupied with gold and precious stones, and is inclined to act towards evil when bewitched by them. Tolkien says in The Hobbit that:

…when the heart of a dwarf, even the most respectable, is wakened by gold and by jewels, he grows suddenly bold, and he may become fierce.

The Hobbit, Chapter XIII, ‘Not At Home’, by J.R.R. Tolkien

Later, it is ostensibly Thorin’s greed that creates a rift between him and the Men and Elves who come to the Lonely Mountain to claim a share of the dragon’s hoard; and that later causes him to wrathful turn on Bilbo when the latter steals the Arkenstone. During the negotiations between Thorin and Bard, we are told:

But also [Bilbo] did not reckon with the power that gold has upon which a dragon has long brooded, nor with dwarvish hearts. Long hours in the past days Thorin had spent in the treasury, and the lust of it was heavy on him. Though he had hunted chiefly for the Arkenstone, yet he had an eye for many another wonderful thing that was lying there, about which were wound old memories of the labours and the sorrows of his race.

“You put your worst cause last and in the chief place,” Thorin answered. “To the treasure of my people no man has a claim, because Smaug who stole it from us also robbed him of life or home. The treasure was not his that his evil deeds should be amended with a share of it. The price of the goods and the assistance that we received of the Lake-men we will fairly pay—in due time. But nothing will we give, not even a loaf’s worth, under threat of force.

The Hobbit, Chapter XV, ‘The Clouds Burst’

And yet another moment when the unwholesome power the dragon’s hoard has upon Thorin can be seen comes after Bilbo delivers the Arkenstone to the gathered Elves and Men, and Thorin agrees to render a fourteenth share of the treasure in exchange for the Heart of the Mountain. However, even after making this deal:

And already, so strong was the bewilderment of the treasure upon [Thorin], he was pondering whether by the help of Dain he might not recapture the Arkenstone and withhold the share of the reward.

The Hobbit, Chapter XV

The Jackson movies, of course, took this greed and made it a central element of his character, lingering on Thorin’s fascination with Smaug’s gold, even turning it into a subplot, and, crucially, implying that Thorin’s dragon-sickness is the root and sole cause for his unkind words and deeds. And, to be honest, I think that this approach misses a huge and important part of the character, that it is a mistake to dwell on Thorin’s dwarvish love for gems, and that this implication glosses over a much more important and narratively intriguing reason for his bad behaviour.

Thorin is greedy, there’s no real denying that. But even as he approaches his lowest moments in the book, he is willing to at least treat with Bard, to a point, as shown above – it is the presence of the Elven-king and the threat of violence or siege that (at least, according to his own words) causes Thorin to hold out. We do not know how things would have gone had the Lake-men approached Thorin without the Elves, and in less warlike manner. But I am inclined to believe that Thorin would have at least been more open in his manner, in how he received their request.

Yet Thorin is also undeniably an antagonistic figure towards the end of the story, and it is interesting to consider which faults of his (instead of or in addition to greed) contribute to this villainous turn. I think that better analyses of his character deal also with his pride, which is a very crippling failing of his as well. Over and over again, Thorin is shown as being unwilling to take advice from others, as being unwilling to admit his mistakes, and as being unwilling to surrender glory or leadership. Much of this is implied in The Hobbit, and is further supported by Gandalf’s telling of the tale from his perspective in “The Quest of Erebor”, as published in Unfinished Tales, where the wizard recollects Thorin’s initial disinclination toward the timid and foolish Bilbo after their initial meeting.

‘I know your fame,’ Thorin answered. ‘I hope it is merited. But this foolish business of your Hobbit makes me wonder whether it is foresight that is on you, and you are not crazed rather than foreseeing. So many cares may have disordered your wits.’

“‘They have certainly been enough to do so,’ I said. ‘And among them I find most exasperating a proud Dwarf who seeks advice from me (without claim on me that I know of), and then rewards me with insolence. Go your own ways, Thorin Oakenshield, if you will. But if you flout my advice, you will walk to disaster. And you will get neither counsel nor aid from me again until the Shadow falls on you. And curb your pride and your greed, or you will fall at the end of whatever path you take, though your hands be full of gold.’

“He blenched a little at that; but his eyes smouldered. ‘Do not threaten me!’ he said. ‘I will use my own judgement in this matter, as in all that concerns me.’

Unfinished Tales, ‘The Quest for Erebor’, by J.R.R. Tolkien

I will use my own judgement in this matter, as in all that concerns me. And while Gandalf outright warns Thorin against greed, he mentions pride also, and first and foremost. Thorin is possessed of a keen sense of his own dignity and nobility, and is often unable to see past either, to his own detriment.

But I think there is a deeper layer, too, which supports Thorin’s pride, but also adds to it, and that is Thorin’s self-awareness, even his cultural awareness. It is commonly accepted that Tolkien’s Dwarves draw at least some inspiration from old Nordic tales and tropes, from their names to their manner. Again, when framed in the way that I presented in the opening couple of paragraphs, The Hobbit is itself a tale of heroic revenge…only, y’know, with the titular Hobbit himself in the mix as an additional, complicating factor.

Gandalf, again, seems to have been keenly aware of this from the very outset of the quest, saying of it in “The Quest for Erebor” (and re-emphasising that pride was a chief danger for Thorin) that:

“So it was that the Quest of Erebor set out. I do not suppose that when it started Thorin had any real hope of destroying Smaug. There was no hope. Yet it happened. But alas! Thorin did not live to enjoy his triumph or his treasure. Pride and greed overcame him in spite of my warning.”

Unfinished Tales, ‘The Quest for Erebor’

However, if Tolkien’s dwarves are based on this historic people, does it not make sense that they would also share cultural practices and concepts with that people? If the Dwarves are modelled after a Scandinavian template, then why would they not tell the same heroic sagas and tales that those Scandinavian peoples told?

Thorin must have been familiar with such tales, and been fully aware that his quest was itself part of that same epic tradition. And, therefore, he must have been aware that he was the hero of this tale he himself was forging, that he had a place in this tale, and it was a central and noble one. I do not mean to say that Thorin ever thought he would be ‘successful’, all too many of these Nordic tales end in defeat, whether great or partial (as implied by Gandalf himself above). But Thorin must have felt that, in taking on the Quest, he was also taking on this mantle of hero, of achiever, of leader, and that consciousness is (I think) what also contributed to his downfall.

Because, as we well know, Thorin achieves very little in his own quest. It is Gandalf who rescues them from the Trolls and from Goblin-town; and the Eagles who rescue them from the pine forest. And then, from that point on, it is Bilbo who achieves most things – rescuing the Dwarves from the spiders and the Elven-king’s prisons, discovering the hidden door, even discovering Smaug’s weakness and (inadvertently) causing the chain of events that lead to Smaug descending upon Lake-town and his doom. Speaking of which, Thorin never even meets Smaug, let alone slays him (or at least dies trying), as the dragon is struck down mid-flight by a man who is also a rightful king, and whose folk have also suffered Smaug’s wrath. But to Thorin (and, intriguingly, also to the reader of The Hobbit), Bard the Bowman is a literal nobody, a newcomer who steals Thorin’s climax from him (in his eyes). And for this nobody to then have the gall to try and take Thorin’s treasure from him? That, I think, is what stung Thorin, more than anything else.

Thorin is transformed, through no special fault of his own (unless it be his own conceit), from self-appointed protagonist to a near-sideliner, in his own story. If you were to rewrite The Hobbit, Thorin could literally disappear from the story after chapter 1 (since we need him to form the company of Dwarves) until his villainous turn after Smaug’s defeat and the siege of Erebor, and we would not really need anyone else to take up his narrative function. That’s a massive chunk of the story for the “hero” to play literally no role, and I think that, over time, Thorin himself became aware of his own impotence.

And that, more than anything else, is what I think stung Thorin’s pride so deeply. It is, I suppose, difficult to blame him. For him to have had his life’s ambition, his glory and his right stripped from him, though he does everything ‘right’ in order to earn it, must surely rankle. And, even worse, his chief ‘usurper’ is an outsider, a homebody, a gentle fool. No wonder Thorin was so furious when Bilbo found, hid and stole the Arkenstone – in a sense, Bilbo had already taken everything else from him (save, perhaps, the dragon’s deathblow…though even that was caused by Bilbo, even if Thorin didn’t remember it). Bilbo, the unlikeliest of thieves, may only have stolen a single golden cup from the dragon’s vast hoard, but he robbed Thorin of something far more valuable. He robbed Thorin of his fate, of his doom, of (in a way) his identity. That, surely, stung much more than any other indignity or misfortune Thorin ever suffered.

And this, to me, is a large part of the appeal of The Hobbit. This contrast between the heroic and epic, and the kindly and homely, is a clear and present theme throughout the book. But to have it encapsulated in Thorin’s character, and with very little recognition (fittingly, given that his own sidelining is a major part of his story) is, to my mind, a brilliant piece of literary reflection and awareness.

Indeed, this then opens up a whole field of questions and problems concerning Thorin. He is, of course, drawn in contrast to Bilbo. The willing hero who was denied his right to act as the protagonist, vs the reluctant hero who became the protagonist through no wish of his own. But Thorin is also, in his own way, a study of that archetypical ancient Nordic hero that Tolkien was so familiar with, and is a biting and critical subversion of that type of character. It is, of course, the doom of Beowulfs and Sigurds to battle dragons, and to die nobly in that battle. But what if, Tolkien asks, that battle, that noble death, never came? What is such a hero when denied a dragon? The answer, of course, is Thorin.

This is also a chief failing of the movies, and a crucial misreading of Thorin’s character. In Jackson’s films, Thorin is actually too effective, too heroic, he plays too great a role. One can point to the baffling ‘gold-sickness’ that Jackson introduces as being the great change between literary Thorin and his cinematic counterpart. But really, Thorin’s enchanted greed is merely a symptom of the greater structural changes to his arc, and an attempt to fix the massive narrative cracks that appear as a result. By giving him extra weight, extra importance, Thorin hews closer to the very type of character model that Tolkien was trying to subvert in the first place. And this, of course, misses the very point of Thorin as a character.

So, Thorin. A hero of another tale, but not the tale that was told. But there is (to me) something deeply relatable about Thorin when presented in this light. He is, quite simply, the second best to Bilbo’s accidental genius. The Salieri to Bilbo’s Mozart (at least as far as fiction would have us believe), the Edison to Tesla. Tolkien would himself play with this again with Aragorn and Boromir, though their relationship is very different to that of Thorin and Bilbo, and Boromir’s redemption and death is not entirely similar to Thorin’s (though there are parallels).

I once jokingly suggested that there was an entire hidden and untold story concerning Gimli in the pages of LOTR. Now, I will say it again, and fully seriously. There is an almost entirely untold story concerning Thorin in The Hobbit. Nay, not simply untold – an unhappening story, if you will. And if it were told, if Thorin were to assume any greater importance in the narrative, it would damage the point that I think Tolkien was trying to make with him. Thorin wants to be important, to be notable, and for him to fall, he cannot be so. It is a strange and tragically subversive tale, the tale of Thorin Oakenshield. And I think it is indirectly one of Tolkien’s most intriguing criticisms of the merits and flaws of the very epic tales that he himself so loved.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Thanks for reading – feel free to check out anything else you may be interested in on the blog, there’s plenty more to discover! Follow me on Facebook and on Twitter to stay up to date with The Blog of Mazarbul, and if you want to join in the discussion, write a comment below or send an email. Finally, if you really enjoyed the post above, you can support the blog via Paypal, and keep The Blog of Mazarbul running. Thanks for reading, and may your beards never grow thin!