You will never be happy

There are a few films in the world that I believe I could watch over and over again. I’m loathe to write what they are (as I may well visit them sooner or later in this blog (also check out this page if you do wanna visit the stories I’ve discussed thus far!)). But there is one that I’ve rewatched at least a dozen times, that I always notice something new to enjoy or consider, and that I’ve been thinking about a lot recently.

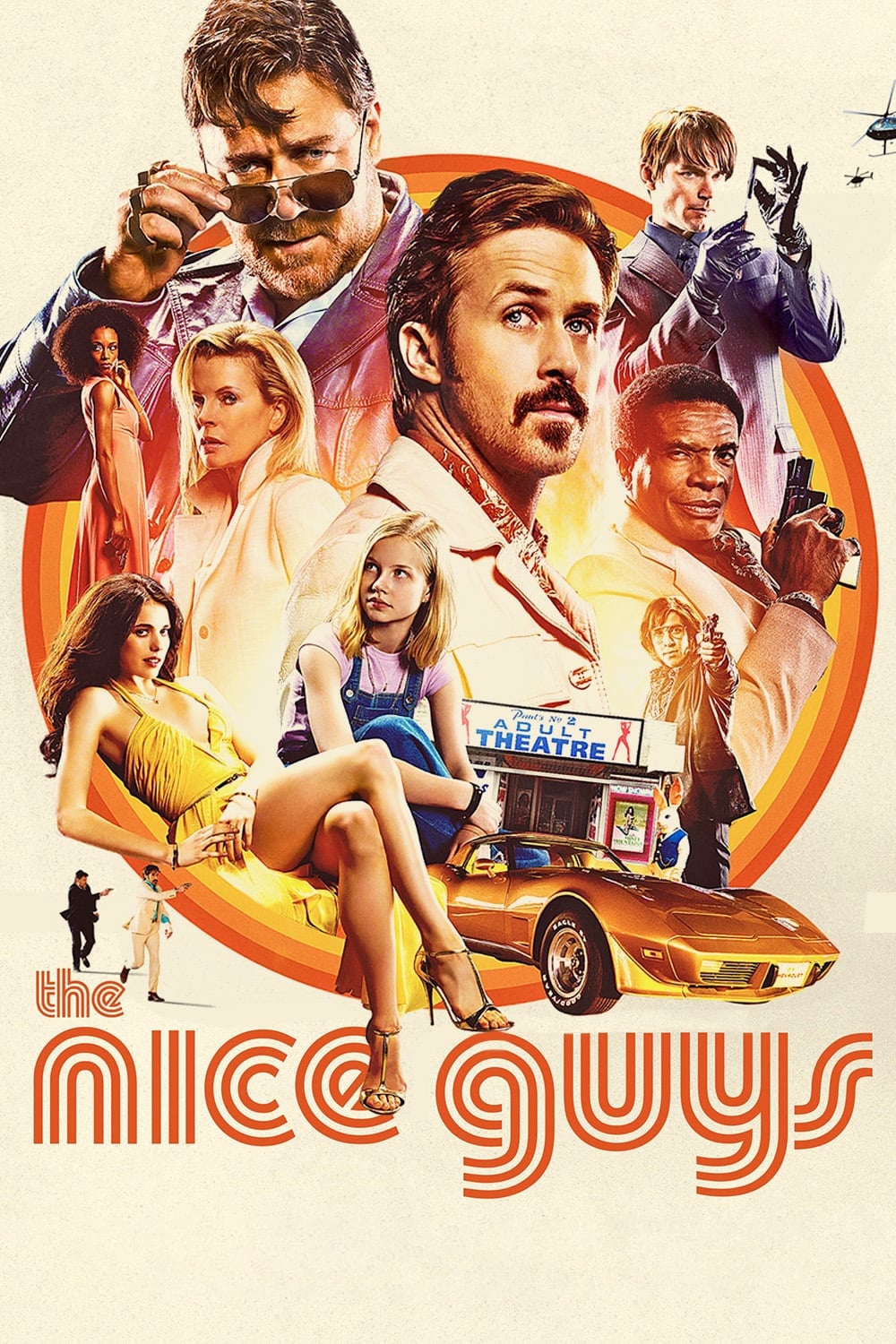

The Nice Guys is a film by Shane Black, starring Russel Crowe and Ryan Gosling as a mismatched pair of investigators in the bright lights and grimy underbelly of L.A. in the ‘60s. It’s also not nearly as known or discussed as I truly think it should be, and it is one of my favourite films ever.

There’s a lot about The Nice Guys which works. Superficially, it looks and sounds great, it is an easy and satisfying watch. The performances of Crowe and Gosling (as well as Angourie Rice, the unofficial third musketeer of this unlikely duo) are incredible. Gosling in particular demonstrates an incredibly keen aptitude for physical comedy, slipping, falling, bleeding (seriously I have never laughed so hard at a man bleeding out – you have to see it to believe it), and (in an early highlight) multitasking on the toilet with impeccable skill.

Crowe, for his part, plays the straight man for the most part, but his sense of comedic timing, his clear joy at the verbal sparring between him and Gosling, and his frequent eyerolls and bewildered double-takes are wonderful. In the centre of the two is Rice as Gosling’s teenage daughter, who more than holds her own in the company of the other two older and more decorated actors. It is not an easy feat for an underaged actress to comport herself with such skill, and nor is it an easy thing for a screenplay to portray a teenager as not being irritating, unbelievable, frustratingly naive or implausibly competent. But The Nice Guys is a masterclass in writing a believable, sympathetic youth, and Rice proves delightfully well-cast.

The Nice Guys is also well-directed, well-acted, well-shot and well-written. None of this is exactly news; for all that it is not overly well known, it is at least critically beloved. But I’ve never really heard anyone talk about just how tight the script is, and how clever, subversive and well-constructed the overall story is. Don’t get me wrong, the rapid-fire wit of the screenplay itself is plain for all to see. Rather, I think that the underlying structure of the story, and many of the choices it makes, are worth further examination.

So, The Nice Guys. Go watch it. Please, watch it, you shall not pass John Howe’s painting below until you have watched it. You won’t regret it. Then come back here in a couple of hours or so, and let’s talk about the film then.

The first scene I wanna examine and break down a little actually comes near the end of the film, as the murderous Tally holds March (Gosling) and Healy (Crowe) at gunpoint (and can be found here if you need a reminder). The scene is delightful, as March and Healy bicker their way through the tense situation. Both comedy and tension are heightened as March finally, memorably pays off a joke set up long before, diving to the ground to draw Healy’s ankle gun – only to learn that the gun, holster and all, was a hallucination.

Since everyone knows that overanalysing a joke ruins it, I really want to overanalyse this particular joke. See, I think it works so well because of everything placed around both payoff and setup. If we rewind to the setup, the gun is introduced at the beginning of a very mundane scene, as March and Healy travel back to March’s home. It feels like nothing more than character building stuff between the pair. The scene is then heightened with surreal comedy (‘Isn’t that right, Bumble?’), distracting us from the gun. Then we get a quick moment of tension generated by shock (‘Wake up!’) which is almost immediately superseded by tension generated by real concern, as the suitcase’s contents are revealed.

By this point, we have almost certainly forgotten the ankle gun, which makes its (non) reappearance at the auto convention all the more surprising, it is literally an anti-Chekhov’s gun. It also helps us to see the later scene from Tally and Healy’s perspective, as March seemingly goes insane, only for us to slowly realise what he is trying to do. Further, by setting up the ankle gun at the beginning of a memorable scene, it ensures that we will remember it…just a little too late, heightening the humour.

This type of delayed joke is rife through The Nice Guys, and it might seem like a lot of work to set up a single punchline. But consider, the car scene that prepares the ankle gun does so much more work. As described above, it also reveals that not all is well with the Justice Department. It reminds us of March’s problems with substance abuse (which is also paid off beautifully during the final setpiece, as March finally pulls himself together). It reinforces the running theme of pollution. Needless to say, it is also a very funny scene in its own right.

And, of course, it also happens to set us up for a delightful piece of physical comedy, a good half an hour later.

Speaking of physical comedy, it’s time to wrap this extended digression up and return to the scene we were already examining; namely, the confrontation with Tally. So, as Healy and March try to deescalate the situation, a knock comes at the door. Tally realises that it is Holly, though, and lets her in, so as to maintain control over all parties. Holly throws a pot of cold coffee at Tally, believing it to still be hot. Tally, starting to lose her patience with these bumbling idiots, takes a step, slips on the coffee in a beautiful moment of slapstick comedy and knocks herself out, allowing our heroes to finally escape.

Slapstick aside, this scene is a great demonstration of an ‘anti-coincidence’, a narrative technique that permeates The Nice Guys from beginning to end (and that I also invented just now). And it’s worth breaking down a little what this technique is, and why I think it works so well.

An oft-quoted piece of writing advice (which I cannot find a source for, alas), is that an author is allowed a single coincidence in any piece of work, preferably near the beginning, and preferably so as to allow the plot to unfold (rather than to solve any problems). Indeed, not only is it permissible, but such coincidences can also be desirable, as they provide an easy way for us to understand why the story is happening when it happens. Luke Skywalker would have been a moisture farmer forever if he hadn’t accidentally bought a particular pair of droids, and Grendel would have feasted on Danish warriors for years had Beowulf not happened to hear about the monster and visit Hrothgar’s halls.

A similar, though not identical rule is reportedly practiced by screenwriters at Pixar Studios:

Coincidences that get characters into trouble are great. Coincidences that get them out of it is cheating.

So coincidences have a place in fiction, but need to be carefully employed. This is because coincidences happen all the time in real life, but they can be narratively frustrating for an audience. This might be because a coincidence threatens to spoil the immersion into a Secondary World – because a coincidence reminds the audience that the author is in charge here, that the characters and plots proceed according to the whim of some other figure, who is external and removed.

But I think there’s a second (if related) reason, too, why coincidences are usually dissatisfying in stories. Namely, a coincidence removes agency from the actions of the characters, makes their own efforts seem petty or useless. In other words, things shouldn’t just ‘happen’ in order to extricate our heroes from a problem in a story, such as when a deus ex machina occurs. The characters themselves have to work for it, they have to earn it, there has to be some reason for why the story unfolds as it does.

We’ve discussed this art of ‘earning’ happy endings before, when looking at eucatostrophic storytelling through the lens of Disney’s Tangled. But, for the sake of a quick recap – a eucatastrophe may seem like a coincidence, but it is not. Rather, a eucatastrophe is an event outside the control of the heroes, but that has nonetheless been earned by the heroes in some way. The Lord of the Rings gives us two such eucastrophes (which are also fairly distinct) during the climactic confrontation within Mt Doom.

First, Gollum reclaims the Ring, only to slip and fall into the fire, thus fulfilling the quest. This may seem like an accident, but it is not. Twice, earlier in the story, Frodo has laid that very doom upon Gollum, that he will fall into the fire if ever he takes the Ring again. Then, as the volcano erupts, Frodo and Sam are saved from death by the Great Eagles bearing them away to safety – another eucatastrophe, and here one earned not by cause and effect, but by the heroic and moral actions of our protagonists.

The Nice Guys is one of the most eucatastrophic pieces of film I have ever seen, which is a surprising sentence. But it is true – the eucatastrophe is present from beginning to end, and is invariably treated carefully. Yet the eucatastrophes of The Nice Guys are often of a slightly different type to those in Tangled, or LOTR. Rather, these eucatastrophes often seem to come about through the actions of our heroes, and despite their actions.

In support of this claim, let’s return to that confrontation with Tally that we described before, which is one of the most protracted and best-realised anti-coincidences in the entire film:

- Healy asks Tally if she has ever really killed anyone, looking to talk her down, only to find out she has murdered three times before.

- March pleads with Tally, telling her that this ‘isn’t her’, that she is not a murderer (despite the evidence to the contrary, as Healy resignedly tells him).

- March then uses the distraction of Holly knocking at the door to dive for Healy’s gun…only to learn that there is no gun there.

- Holly finally enters, but Tally is not taken by surprise, making it seem as if she has failed.

- Then Holly throws the coffee on Tally, trying to scald her.

- Finally, after all that, Tally slips and is concussed, the eucatastrophe has come to pass.

So, what do I mean when I say that this is an example of an ‘anti-coincidence’? Because it is indeed an accident, a happy chance, that proves to be Tally’s undoing – had she not slipped, she would have shot our heroes, and the movie would be over. However, Tally only slips because of Holly’s actions – Holly is still the cause, even if the effect is other than she had planned.

Further, consider the outline of events above. In another film, any of those things listed would have been sufficient to extricate March and Healy from the crisis. In another film, Healy would have talked Tally down with a crisis of conscience. In another film, Holly would have burnt Tally with the coffee. And in another, much less funny film, March would have grabbed Healy’s ankle gun and filled Tally with holes. There were multiple moments of earned release well before Tally’s fall, each of which are individually averted, and each aversion also heightens the eventual, (seemingly) unearned resolution. In truth, that resolution has been earned, both by cause and effect (Holly spilled coffee, Tally slipped on that coffee), and by narrative logic (our heroes have done multiple things in order to resolve the problem [albeit unsuccessfully]), and so it is internally satisfying, even though it is ‘just’ a coincidence that leads to the actual resolution.

The Nice Guys is packed with such moments, nearly all of which are earned. March and Healy go to the airport hotel to find Amelia, they go to the effort of figuring out the clues where she is, of getting her floor from the barman, of going up in the elevator to get her. All they fail to do is to actually find her, rather opting to flee the bloody massacre left by John Boy…only for Amelia to literally land on their car. March and Healy have done the work, but the result happens by chance…though they have earned that chance. March finds the corpse of Sid Shattuck because he happens to fall from a balcony, and because he happens to land near the latter’s body…at a party that he was only at in order to find Shattuck.

Even the bad guys get in on the anti-coincidence action, as John Boy goes to assassinate Amelia, and is barely driven off by the concerted efforts of March and Healy…only to happen across her as she herself rashly flees the scene. John Boy’s little shrug and ‘huh’ says it all as his target jumps willingly in front of him in an excellent anti-coincidence.

I’m not suggesting that such anti-coincidences are unique to The Nice Guys. At the same time, though, I cannot recall ever seeing another story which uses this technique so frequently, nor so effectively. There’s something admirable about how restrained Shane Black is in setting up these anti-coincidences, and in going the extra mile to resolve them. If he had wanted, there were any manner of satisfying ways to incapacitate Tally that were set up well. However, by refusing to use these options and averting them at every turn, the tension remains high throughout the film. The resolutions still feel earned and satisfying. And, of course, it is very, very funny.

This all may make it seem as if The Nice Guys understands the eucatastrophe merely as being a tool for flippant effect, a technique ripe to be exploited for silliness. And, were these all the eucatastrophes of The Nice Guys, then perhaps that would be fair. But I think there’s a deeper awareness of the eucatastrophe, too, that runs through the film, and that this awareness justifies these flippant and small eucatastrophes as being part of a larger whole. And, for anyone who is doubtful of this idea, I would ask you to consider the longest-lasting setup/payoff in the entire film, the setup that (in a way) informs the entire rest of the film.

I would ask you to consider March’s hand.

Our establishing encounter with Gosling’s March sees the investigator fully dressed and fast asleep, groggily awakening in a full bathtub. The scene is as tragic as it is comic, establishing March’s character with remarkable ease. But there’s one element which really sets the tone for his character – the bleak, self-inflicted scrawl a drunk and miserable March gifted to himself at some point before he passed out.

You will never be happy 🙂

The self-loathing words establish a lot about March’s character, of course, but they also serve as the film’s longest-lasting setup. Because a good hundred or so minutes later, after Healy and March have overcome the numerous (and occasionally self-inflicted) monumental setbacks thrown in their way, at the final moment when March finally lays his hands for good on the all-important porno, he catches a glimpse of his hand once more, where, in the chaos and scuffling, one little word has been smudged and erased.

And in the midst of all the chaos and stress and tension, the film just…stops. It lingers for a moment, as March takes in this strange little chance, before snapping back into action. Except the action is all over, March finally lays hands on this all-important reel. Healy gives in to mercy. The Nice Guys have won. And it’s heralded with March seeing those words, seeing a promise that ‘You will be happy’.

It’s a weird, incongruous little moment. In contrast to the rest of the film’s dense plotting, those words have never once reappeared in any form. It’s also played very, very straight – it is heightened, even a little surreal, but fully earnest as well. There’s no quip, no release, no joke. Just a sudden, sincere promise that the film itself makes to March, and by extension, to the audience.

And it works. It works because we’ve seen March grapple with his demons – they are not yet overcome, but they have certainly been recognised and addressed and rejected for at least one day. But it also works because the entire film has been reinforcing the eucatastrophe. Those words haven’t reappeared because they do not need to, because the central theme of the film is being reinforced over, and over, and over again, every single time a eucatastrophe happens. March has sweated, feared and bled to do the right thing for the whole film. He’s often done the right thing the wrong way, or he’s tried to do the wrong thing and wandered into the right thing, but he’s done it. And throughout the final confrontation at the expo, March (and Healy, as well), finally overcome every personal temptation, every weakness, that is thrown their way.

So at the last, as March finally achieves his goal through his own effort, a eucatastrophe occurs, but it isn’t a eucatastrophe that alters the climax in any material way. Rather, it is a eucatastrophe that reassures March and the audience alike that March himself has changed, and that he can continue to change. It’s a promise that he can be better, that he can be happy. And incredibly, it is a promise that feels genuine and earned and legitimate, partly because March has indeed done that personal work.

However, it also feels earned because the film itself is so earnest, so committed, to the eucatastrophe as a force of nature. We’ve seen dozens of small eucatastrophes play out throughout, such as Tally’s accident. And all of these eucatastrophes were earned in some way. So, why should not this big and personal eucatastrophe, that was set up from March’s very introduction, be any different? Throughout, the film has reinforced the eucatastrophe as being something potent, and now, at the last, the film’s commitment to these little eucatastrophes allow us to believe the film’s overall eucatastrophe. March will be happy, because everything that has occurred across the entire story has shown us that anti-coincidences have power. Sure, it’s just happenstance that the ‘never’ written on March’s hand has been smudged away. But just because it is happenstance does not mean that it has no meaning, that it cannot also be true.

It feels very strange to recommend The Nice Guys as being a profoundly beautiful and eucatastrophic film. It is a film that features foul language, pornography, murder and corruption, alcoholism, and other minor depravities. But it is also remarkably focused on its message of hope and joy, and not in a frivolous and insulting manner. Hope and joy don’t just happen, according to The Nice Guys, they have to be worked for and earned. They are hard to attain, and vanish easily, but they can be achieved and are worth achieving. It is a surprisingly earnest and innocent sentiment at the heart of the film, and the film itself never abuses that message, never forces it upon the audience. But it is very successful at communicating it all the same, and I think that part of this success is due to the fact that it is not overly saccharine – but the other part is because so much of its plotting, twists and turns are bent toward the eucatastrophe.

There is a darkness, a cynicism, a near-delight in grime and smut and violence on display for all to see in the film, and it would be easy to assume that The Nice Guys is therefore a cynical film. The world is bleak and unhappy and terrible things happen all the time, according to the film itself. Even the end of the film reinforces that, as the rich buy their way out of prosecution, and March and Healy amicably bicker their way to the end credits. But, within that grim world, there is a very earnest and sincere belief in something good, too. March and Healy are far from being reformed characters come the end of the film, but they have both changed for the better, and have also both earned a true happiness, the happy ending of a fairy tale – the sort of happy ending that Holly still believes in, because she is young and innocent and right.

In the world of The Nice Guys, happiness has to be both earned and bestowed, there is no one or the other, and I think that might be what the film is all about, in the end. Mind, it is also a very funny film, and a very well-constructed film, with twists and turns and a comedic palette that ranges from the ridiculous to the truly ridiculous. It is lightning fast, densely and cleverly plotted, memorably framed and shot, and every single actor in it is truly excellent.

Naturally, all of this technical excellence is easy to see and appreciate for any viewer of the film. But I do truly believe that The Nice Guys goes beyond, as well, in its underlying message and how it communicates that message. I do not know how well-read Shane Black is on the eucatastrophe, chances are good that he’s never heard of it. But there does seem to be some awareness and understanding of it all the same, an awareness of the eucatastrophe that permeates The Nice Guys. And, ultimately, that is why I adore it, and why it is one of my favourite films.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Thanks for reading – feel free to check out anything else you may be interested in on the blog, there’s plenty more to discover! Follow me on Facebook and on Twitter to stay up to date with The Blog of Mazarbul, and if you want to join in the discussion, write a comment below or send an email. Finally, if you really enjoyed the post above, you can support the blog via Paypal, and keep The Blog of Mazarbul running. Thanks for reading, and may your beards never grow thin!