Of Aulë and Yavanna: Tolkien’s Odd Couple

‘Nonetheless they will have need of wood.’

With that brilliantly offhand one-liner, Aulë and Yavanna cemented their status in the minds of many Tolkien lovers as being Eä’s first and best odd couple. He, a rash craftsman, master of forge and hammer, lover of stone and gem and that which is imperishable and unchanging. She, a lover of beasts and plants, the bringer of growth and giver of sustenance, who cherishes all that sprouts and blooms and flowers, all that lives.

Given Tolkien’s interest in the themes of nature and industry, it might seem obvious to pair these two Valar together, precisely for the dissimilarities between them. Yet all of the other wed Valar seem to be well-fitted to their spouse, to be rather more similar than dissimilar. Manwë and Varda, between them, rule over all within the heavens, all that is celestial and high. Tulkas and Nessa are the great athletes of the Valar, and both are swift and filled with delight. Mandos sees near-all that has passed or will come to pass, and Vairë records all in her tapestries. So on and so forth – nearly all of the wed Valar seem complementary to their partner, like, and yet not wholly alike.

Aulë and Yavanna, on the face of it, are rather less similar to each other than any other pair of wed Valar. Indeed, it is easier to see their differences than it is to recognise their similarities, to see how they exist in opposition rather than harmony. And this is strange when compared to the other Valar, as there is not the same sense of conflict and opposition between the other pairs. If it were Tolkien’s intention to pair opposites, then surely grim Mandos and dancing Nessa would be better fit for each other, yet it is not so. Why, then, are Aulë and Yavanna an odd couple, and further, are an odd couple among un-odd couples? What reason might there be for their union?

The answer is, I think, that this popular conception of these two Valar as an odd couple is not wholly accurate in the first place. While it is undoubtedly true that they are not fully alike, and that there is some conceptual tension between them, I don’t think that this is because they’re opposites – rather, Aulë and Yavanna are (as with their fellow Valar) two halves of a whole. And I don’t think that this is recognised nearly enough. So that is the task of this post, to illustrate how Aulë and Yavanna aren’t really the Valar of stone and tree. Of course, they are also the Valar of stone and of tree, but I think there’s something much deeper to them, too. Of all the Valar, it is Aulë and Yavanna who love creation and creativity above all – but I am getting ahead of myself.

First, it is prudent to turn to the descriptions of the two, as laid out in the Valaquenta.

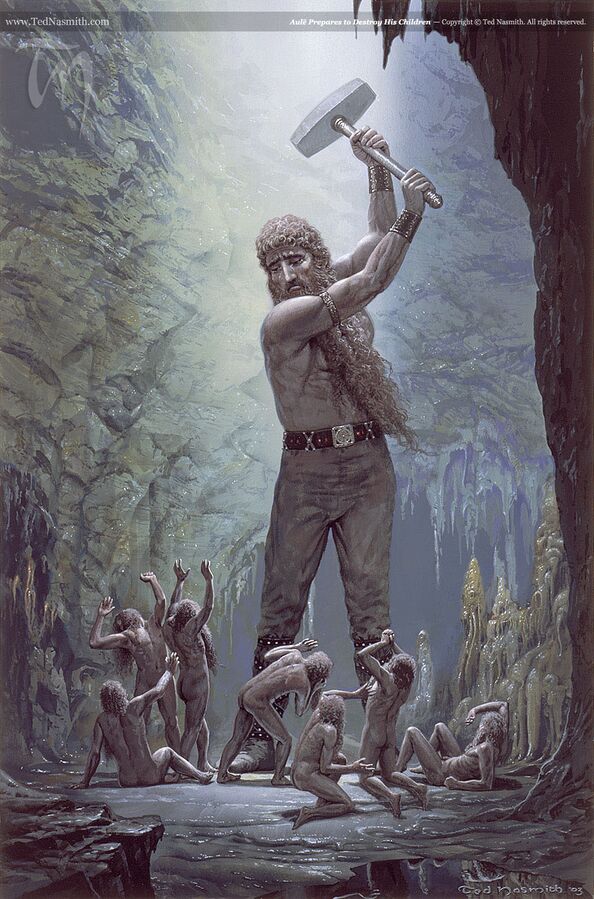

Aulë has might little less than Ulmo. His lordship is over all the substances of which Arda is made. In the beginning he wrought much in fellowship with Manwë and Ulmo; and the fashioning of all lands was his labour. He is a smith and a master of all crafts, and he delights in works of skill, however small, as much as in the mighty building of old. His are the gems that lie deep in the Earth and the gold that is fair in the hand, no less than the walls of the mountains and the basins of the sea. The Noldor learned most of him, and he was ever their friend. Melkor was jealous of him, for Aulë was most like himself in thought and in powers; and there was long strife between them, in which Melkor ever marred or undid the works of Aulë, and Aulë grew weary in repairing the tumults and disorders of Melkor. Both, also, desired to make things of their own that should be new and unthought of by others, and delighted in the praise of their skill. But Aulë remained faithful to Eru and submitted all that he did to his will; and he did not envy the works of others, but sought and gave counsel. Whereas Melkor spent his spirit in envy and hate, until at last he could make nothing save in mockery of the thought of others, and all their works he destroyed if he could.

The spouse of Aulë is Yavanna, the Giver of Fruits. She is the lover of all things that grow in the earth, and all their countless forms she holds in her mind, from the trees like towers in forests long ago to the moss upon stones or the small and secret things in the mould. In reverence Yavanna is next to Varda among the Queens of the Valar. In the form of a woman she is tall, and robed in green; but at times she takes other shapes. Some there are who have seen her standing like a tree under heaven, crowned with the Sun; and from all its branches there spilled a golden dew upon the barren earth, and it grew green with corn; but the roots of the tree were in the waters of Ulmo, and the winds of Manwë spoke in its leaves. Kementári, Queen of the Earth, she is surnamed in the Eldarin tongue.

Valaquenta from The Silmarillion, by J.R.R. Tolkien

Nature vs craft, stone vs wood, growth vs industry. These do seem to present rather opposing characteristics, but I’m particularly interested in that final conflict – that of growth and industry. For, in a way, both are oriented toward the same end, a creative end.

In Yavanna’s case, she nurtures and delights in creation itself, in the unfolding of creation and its own spontaneity. She does not create, though she does foster creation through growth and renewal, in a way that none of the other Valar do. And, while all of the Valar love that which is created, Yavanna seems to be particularly loving of creation in a similar way to how Eru loves creation. In both cases, their love is directed toward loving creation and delighting in it not just for its own beauty (though undoubtedly she does love its beauty!), but for its own sake, for its potential and its life. Further, there is something distinctly unselfish about Yavanna’s love for creation – she, too, wishes for creation itself to delight in itself and in that which exists around it, which is also a very Eru-ish type of love.

Aulë, too, loves creation, but his love manifests differently to that of Yavanna. Where Yavanna sees creation and wishes for it to propagate of its own accord, Aulë sees creation and wishes to be a part of the act of creation itself. Aulë is, unsurprisingly, the lover of sub-creation, it is his desire to partake in the act of creation through the shaping and fashioning and changing of something into something better, into something that it previously was not. And, to be clear, that sub-creative urge is in actuality a creative urge – as discussed previously, the creative urge is itself good because it is of God, and that creative urge moves us (and Aulë) to sub-create. Or, to put it another way, Aulë possesses a divine love for the act of creation and making – he, too, is like to Eru in that love. But where Yavanna’s love is a love for that which is created, Aulë’s love is for creating. Both are an aspect of Eru’s love, a divine love – both are a love for aspects of creation.

So, Aulë and Yavanna are both creative and lovers of creation, yet also in very different ways. Where Aulë sees something and wishes to change it, Yavanna sees something and wishes it to change of its own accord. Aulë fashions and crafts and directs, while Yavanna nurtures and coaxes and guides. Yet both are oriented toward a similar end, and with a similar delight. Further, both Yavanna and Aulë are not merely content to foster and to partake in creation – as with their own Creator, they are eager to share in creation with others also, to share in creation with others who will love nature and craft even as they do. And in examining the Dwarves and the Ents, it is possible to see how the creative tendencies of these beings further reflect and inform our understanding of their odd-couple patrons.

Dwarves, famously, are (like their erstwhile maker) crafters of wondrous and beautiful things, cunning with hand and mind. Their sub-creative impulses are direct and dominative, seeking to shape according to their will and vision. The Ents, though, are shepherds and stewards. They do not shape trees and bushes according to their design; rather, they nurture and cultivate plantlife so as to allow it to flourish of its own accord. Ents are just as creatively inclined as Dwarves, but their desire is to allow that which they love to develop and grow in beauty, free from harm or interference. As with their patrons, the Dwarves wish to fashion and alter, while the Ents wish to nurture and guard.

Indeed, one can take a step back from these comparisons between Dwarves and Ents to another, larger comparison – that of all the Valar, Aulë and Yavanna are the only ones who have ‘their’ people, who had the same creative urge that Eru did to share in creation with people who would delight in creation, people who would love creation and gain joys from it in the same manner as their creator does. No other Vala has living beings that are especially associated with them in that way (or at least, if they do, then they do not enter the histories in the same way that Dwarves and Ents do). Manwë, of course, is served by the Great Eagles, but the nature of the Eagles is rather less clear than that of the Dwarves and the Ents (notably, Tolkien seems to have been unsure as to what degree of independence the Eagles possessed at all, a doubt that seems not to have been shared with the Ents). And in any case, the role and function of the Eagles is different again – though they may well have autonomy, that autonomy is directed toward fulfilling the will of Manwë in a very immediate manner. The Eagles are servants, while the Dwarves and the Ents are fully independent – even if their inclinations happen to serve the interests of Aulë and Yavanna respectively, they are not in any way beholden to them.

In reading of the creation of the Dwarves, it is easy enough to skip over Yavanna’s petitioning for the Ents, thanks in no small part to Aulë’s very funny one-liner at the end of the story. But is it not illustrative of Yavanna’s character that, upon learning of the Dwarves, she too pleads that there be living creatures who are inclined to protect and nurture those things that she loves? Neither Aulë nor Yavanna cause the Dwarves and the Ents to be made in order to have dominion over them. Rather, both Dwarves and Ents are made both to share in the delights of creation and enable sub-creation, and to do so in a way that is pleasing to the Vala they are each associated with. And those creative aspects of each are, I think, incredibly important. Tulkas does not wish that there be Children who wrestle all day, nor does Oromë seem to wish that there were Children who would value hunting above all. Aulë and Yavanna, though, are fundamentally creative beings, more so than any of the other Valar, and just as their Creator created the Ainur and the Children so as to share in the wonders of creation with them, so too do Aulë and Yavanna wish to have people to share in the wonders of creating and of that which is created, respectively.

Finally, I think there are another pair of characters who provide a striking parallel between the creative impulses of Aulë and Yavanna – namely, Saruman and Radagast, the Istari of each respectively.

The superficial similarities between Saruman and Aulë, lovers of metal and craft and wheels, and Radagast and Yavanna, who favour beasts and birds and flowers, are obvious. But Saruman’s very strategy to defy Sauron is founded in principles of order, of knowledge, and in the end, of domination. This domination in particular is very interesting, as Aulë’s own instincts are themselves dominative – Aulë wishes to exert his will upon that which is external to him, in order to better it. This is not to say that Aulë wishes for domination – indeed, he himself (and Eru seems to believe him) claims otherwise in explaining his fashioning of the Dwarves:

Then Aulë answered: ‘I did not desire such lordship. I desired things other than I am, to love and to teach them, so that they too might perceive the beauty of Eä, which thou hast caused to be.

Quenta Silmarillion, from The Silmarillion, Chapter 2, Of Aulë and Yavanna, J.R.R. Tolkien

Nonetheless, there is a dominative quality to Aulë’s work, and in falling to evil, Saruman seems to embrace those principles. To Aulë and a ‘good’ sub-creator, domination is a means to an end, and the end itself should always be a good one and not overshadowed by the means. Saruman, though, has forgotten the end and embraced the means. Saruman has set aside lordship for the sake of serving (for to be lordly is in itself no bad thing), and taken up lordship for its own sake, as he memorably declares to Gandalf when his treachery is revealed.

“…We can bide our time, we can keep our thoughts in our hearts, deploring maybe evils done by the way, but approving the high and ultimate purpose: Knowledge, Rule, Order; all the things that we have so far striven in vain to accomplish, hindered rather than helped by our weak or idle friends. There need not be, there would not be, any real change in our designs, only in our means.”

The Lord of the Rings, Book II, Chapter 2, ‘The Council of Elrond’, by J.R.R. Tolkien

And in taking up and unhealthily focusing on that dominative aspect that sub-creation requires is not to say that Saruman loses his skill for sub-creativity, not at all! Rather, the direction of his knowledge and passions has become disordered, perverted, albeit in a manner that is consistent with Saruman’s interests and priorities.

We are granted a less clear understanding of Radagast’s character, but the little that we see seems to show him as being rather less oriented toward rule and domination, and rather more toward shepherding and nurturing. Significantly, we are not ever told whether Radagast was a member of the White Council or not. At best, then, he was a member but contributed relatively little…and I rather suspect that he was not a member at all, that such policies and strategies and direction did not come naturally to the Brown Wizard. Indeed, it may not be wholly uncharitable to say that, while Saruman had some sort of strategy that ultimately failed and led to ruin, at least he had a strategy…Radagast, perhaps, did not. If Saruman’s great error was in overstepping his authority and seeking domination, Radagast’s may well have been that he failed to properly rise to his level of authority at all, that he was passive when he should have been active.

There is a deep-rooted resistance among many people to the idea that Radagast, originally a Maia of Yavanna, ‘failed’ in his mission (as did all the wizards save Gandalf), something that Tolkien himself stated:

Indeed, of all the Istari, one only remained faithful, and he was the last-comer. For Radagast, the fourth, became enamoured of the many beasts and birds that dwelt in Middle-earth, and forsook Elves and Men, and spent his days among wild creatures.

Unfinished Tales, ‘The Istari’, by J.R.R. Tolkien

But again, there is a sort of symmetry there, an indication of the potential shortcomings of both Aulë and Yavanna’s methods. Saruman, the servant of Aulë, falls more obviously into evil and wrong-doing in his seeking to dominate and to rule. Saruman has fallen into error in forgetting that this rule should be oriented toward betterment for others, he has become arrogant in his skill and knowledge and believes that this knowledge grants him authority.

But Radagast, too, illustrates the possible pitfalls of Yavanna’s ways. When taken to a logical extreme, this focus on guiding without dominating, watching without forcing, can lead easily to apathy, to idleness, to solitude. It is true that Radagast never falls nearly as far as Saruman does, to be sure. But Tolkien does not say that Radagast was wicked, merely that Radagast also failed. Or, to put it another way, Saruman not only failed, Saruman also actively worked against and hindered the mission he was set to fulfil. Radagast did no such thing, he did not fail as ‘greatly’, nor as actively as Saruman! But that does not excuse Radagast’s own failure, either – and I think that the failure of both characters is, at least on a certain level, a comment upon the possible shortcomings of either philosophy regarding creation.

This is also not to say that Aulë or Yavanna are themselves wicked or even inclined toward wickedness. Rather, all of the Valar have dominion over some thing that is good, but that can be directed towards evil if unmeasured. Ulmo’s waters can freeze and burn and drown, Mandos’ judgements must be governed by both wisdom and by pity, and the hunts of Oromë should not glory in bloodshed nor in suffering. So, too, is it possible to pervert Aulë’s love for creativity and Yavanna’s love for creation, and Saruman and Radagast are, in their own ways, a really interesting commentary on just that.

And, to bring it back to our original odd couple, it is a further illustration of the ways in which they are in fact similar, of the ways in which they are well-suited for each other. Aulë and Yavanna are in fact perfectly suited, precisely because they are similar yet not the same. Their differences, of course, are well-known and easily highlighted. But I do think that their similarities, their mutual love for creation (and the different ways in which that love manifests and is realised) are actually just as interesting, and make the characters of each rather fuller and more compelling.

It is difficult to sum up this passion, this love for creation that Aulë and Yavanna both share, this love that is so overwhelmingly potent that they cannot contain it and must share in its joys with other thinking beings, any better than Aulë himself does in speaking with Eru. And while Yavanna may not share Aulë’s love for sub-creation, and he may not be content to sit by and marvel in creation as she does, I do believe that that common ground is the reason for their union and mutual love – that of all the Valar, Aulë and Yavanna between them know best the mind of Eru the Creator.

Then Aulë answered: ‘I did not desire such lordship. I desired things other than I am, to love and to teach them, so that they too might perceive the beauty of Eä, which thou hast caused to be. For it seemed to me that there is great room in Arda for many things that might rejoice in it, yet it is for the most part empty still, and dumb. And in my impatience I have fallen into folly. Yet the making of things is in my heart from my own making by thee; and the child of little understanding that makes a play of the deeds of his father may do so without thought of mockery, but because he is the son of his father…As a child to his father, I offer to thee these things, the work of the hands which thou hast made.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Thanks for reading – feel free to check out anything else you may be interested in on the blog, there’s plenty more to discover! Follow me on Facebook and on Twitter to stay up to date with The Blog of Mazarbul, and if you want to join in the discussion, write a comment below or send an email. Finally, if you really enjoyed the post above, you can support the blog via Paypal, and keep The Blog of Mazarbul running. Thanks for reading, and may your beards never grow thin!