Give me a king whose chief interest in life is stamps, railways, or race-horses; and who has the power to sack his Vizier (or whatever you care to call him) if he does not like the cut of his trousers.

J.R.R. Tolkien, Letter 52 to Christopher Tolkien

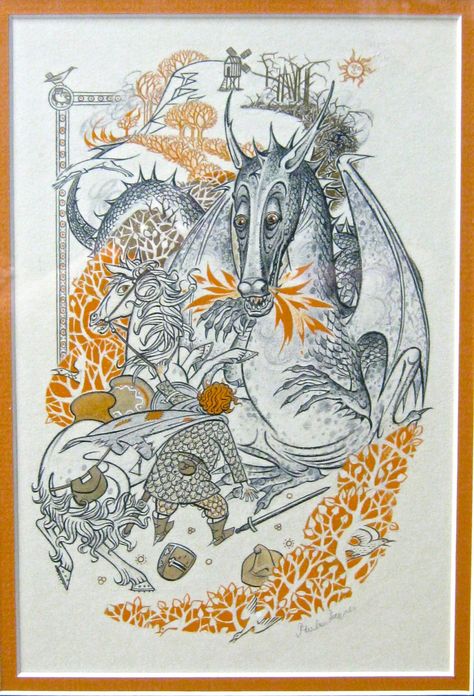

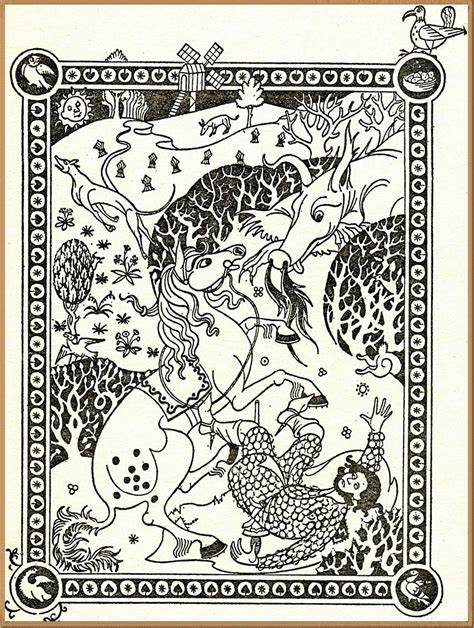

It is not difficult, I think, to see Farmer Giles of Ham as being at least somewhat representative of Tolkien’s idealised monarch. By all accounts, Giles is a perfectly decent ruler – the Little Kingdom grows and thrives under his reign. He treats his friends and allies generously, and his enemies (chiefly the King and Chrysophylax) with magnanimity (though there is a decidedly humanish vengeance in Giles’ treatment of the miller and the blacksmith!). And of course, he is wise without conceit, and wily without deceit – all in all, Giles feels like a decidedly Tolkieanian monarch.

All of this makes sense, of course, in a story like Farmer Giles of Ham – it is, arguably, one of Tolkien’s lightest and least profound stories of his career, a fanciful fairy-tale by a philologist for his family. So of course it also features one of Tolkien’s lightest and least profound heroes in the blustering Giles. Giles is in all likelihood Tolkien’s least profound protagonist, the story does not demand complexity of him. He’s a farmer, he likes beer and comfort and old tales of great deeds, and he dislikes millers and trespassers.

On the face of it, there really isn’t much to study in the good farmer’s character – and honestly, one would be right! Or, perhaps, it’s better to say that one would be mostly right, because there is a bit going on under the surface with old Giles, Tolkien’s unlikeliest of heroes in a panoply of unlikely heroes.

We can divide Giles’ career into three distinct phases, each of which marks a turn for his character. The first is, of course, also the story’s inciting incident – the coming of the giant to Ham. Prior to the giant’s coming, Giles is a decidedly ordinary sort of fellow. We’re told that he has a red beard, that he can bully and brag better than Garm, and that:

He had his hands full (he said) keeping the wolf from the door: that is, keeping himself as fat and comfortable as his father before him. The dog was busy helping him. Neither of them gave much thought to the Wide World outside their fields, the village, and the nearest market.

In short, Giles is a completely normal chap (which the mention of the Wide World further emphasises), until his fateful encounter with the giant – but more on that later. As for the second turn and transformation of his character, this comes during Giles’ second encounter with Chrysophylax. The narrator first draws our attention to it when Giles threatens his wily foe with pursuit, should the dragon try and escape back into his lair:

The mare sniffed. She could not imagine Farmer Giles going down alone into a dragon’s den for any money on earth. But Chrysophylax was quite prepared to believe it…And maybe he was right, and the mare, for all her wisdom, had not yet understood the change in her master. Farmer Giles was backing his luck…

Later, as Giles parades back to Ham with his ever-growing retinue, the narrator emphasises this change in him by way of the delightfully forthright observation that ‘[Giles] was beginning to have ideas.’ These ideas, of course, manifest in the story’s finale, and Giles’ act of rebellion against King Augustus Bonifacius – in short, with Giles finally realising his monarchical potential.

Notably, the character of King Ægidius is not so far removed from that of simple Farmer Giles – both of them are, fundamentally, concerned with driving giants (whether literal or political) from the borders of their land! However, the Giles at the end of the story now possesses the wisdom and the foresight to effectively challenge the wrathful King, using guile (and a live dragon) to his full advantage.

But there is, of course, also an intermediary version of Giles, and it is with this Giles that the story is fundamentally concerned. This Giles is born on the fateful night when the giant comes to visit – it may be Farmer Giles who steps out, blunderbuss in hand, to drive off the giant, but it is Giles the (terribly reluctant) Hero who returns home again, and it is Giles the reluctant hero who occupies most of the story…right up until he starts ‘having ideas’.

But before Giles fully realises his potential, perhaps the most striking elements of his character are his incongruity, and his lack of ‘merit’. The second, in particular, may seem harsh, but I don’t think it’s unwarranted. Because really, what does Giles actually do? He shoots the giant, of course – but almost purely by chance.

The moon dazzled the giant and he did not see the farmer; but Farmer Giles saw him and was scared out of his wits. He pulled the trigger without thinking, and the blunderbuss went off with a staggering bang. By luck it was pointed more or less at the giant’s large ugly face.

To add (minor) insult to (near-insignificant) injury, Giles not only doesn’t kill the giant, he doesn’t register to the giant, who is driven away out of annoyance and inconvenience rather than fear. Not, of course, that the village knows this (or even Giles himself, for that matter), but it does rather underline the point that Giles’ initial triumph is near-totally undeserved.

Not totally undeserved, perhaps – after all, Giles had the courage to go out on that dark night to put the giant to rights. But to the farmer, especially once the heat of the moment had passed, I can’t help but suspect that (much as he enjoyed the minor attention and fame) he must have rather felt that it was not wholly ‘earned’, as it were.

Certainly he at least did not become convinced of his own mighty heroism, as when Chrysophylax turns up, Giles is amusingly reluctant to actually go out and slay the terrible dragon. But that reluctance goes beyond comedy, too – there’s one moment in particular, just before Giles learns that he’s been gifted the sword Caudimordax, that is rather telling concerning Giles’ state:

The parson (and the miller) hammered on the farmer’s door. There was no answer, so they hammered louder. At last Giles came out. His face was very red. He also had sat up far into the night, drinking a good deal of ale; and he had begun again as soon as he got up.

Giles is, in short, genuinely nervous, and it’s difficult to blame him. And even once Giles’ arm is sufficiently twisted, his victory over the wicked worm is due in no small part to his mare and his magic sword, and is enabled by a misjudgement on Chrysophylax’s part. Again, Giles is in the right place at the right time, and scrapes out of his fix with a little luck, but it’s difficult to ascribe this initial triumph over the dragon to any skill or brilliance on his part, and (again) I think Giles is fully aware of this.

Giles has, in short, somehow managed to fail his way to success, as it were. And again, this may be a very uncharitable take concerning Giles – it is hardly as if the poor old farmer could have done much better than he has, after all! He’s simply been the wrong farmer in the right place twice now, and things have largely worked out for him – but a great number of his peers (and betters) are now ascribing all sorts of excellence to him, as the king’s letter icily expresses once it becomes clear that Chrysophylax ain’t in a hurry to come back any time soon.

Inasmuch as the said Aegidius has proved himself a trusty man and well able to deal with giants, dragons, and other enemies of the King’s peace, now therefore we command him to ride forth at once, and to join the company of our knights with all speed.

So we have Giles, in his old helmet and homemade mail coat (with rather too much coat and some fairly haphazard mail), riding in the midst of all these fine knights and lords. And this, really, is the crux of this particular post – namely, that I daresay many people have experienced just such a Gilesian moment. Stuck in a situation, seemingly by accident rather than actual merit, and convinced that we’re considerably shabbier and poorer-clad than our peers. Giles is, I think, experiencing something of an impostor syndrome moment as he rides out.

To be clear, this is merely my reading of the text, and there’s a bit of interpretation on my part – I think that trying to claim that Giles’ psychological state can actually be analysed in detail is a bit of a stretch, given the light tone of the overall story. Similarly, I don’t think Giles is meant to be an allegory for impostor syndrome (apart from ‘allegory’ being a bit of a dirty word in Tolkien circles, impostor syndrome wasn’t actually described until after Tolkien’s death). Rather, what I’m trying to express is that Giles’ incongruity in this moment is exaggerated, heightened, and that when this incongruity is coupled with his very impressive accomplishments and lack of actual ‘accomplishment’ in accomplishing them, it all adds up to a portrait of a sham in mock-knight’s armour, and that seems very deliberate to me.

And though I also doubt that Giles is meant to be in the least bit autobiographical, it’s also easy to see a little of Tolkien himself in this impostorish interpretation. Tolkien, too, did not fit comfortably into the rarified academic circles in which he found himself – a middle-class orphan, a Catholic amongst Protestants and humanists, and a lover of fantasy among philologists who apparently cared more about what the words were than what the words said. It is not at all difficult to imagine Tolkien being terribly self-conscious of his own ‘armour’ and achievements, especially in the early years of his career.

The irony, of course, is that Giles is actually the odd man out, the ‘impostor’ among the lordly knights, in that he and he alone manages to forestall Chrysophylax (for the second time, for good measure!) where all the shining knights are killed or scattered. And, indeed, one can easily argue that Giles has ‘earned’ his ‘knighthood’ (being neither a knight, nor having really earned it) just as much as all the real knights in the company that rides to the mountains. Giles may not have done much beyond being in the right place, yet that would still seem to be as much (or more) as any of the King’s knights have ever managed…but Giles, of course, cannot know that. So prior to the battle in the mountains, Giles seems decidedly ill at ease, and who can blame him? And, sure enough, once the vain and simpering knights have had their true colours shown, Giles finally begins to back himself – and thus the third of our Gileses is born, and the Farmer becomes King.

There is, I think, something decidedly unNigglish about Giles. As I argued last week, Niggle’s most notable for his mediocrity, for his littleness. Giles, on the other hand, is notable in spite of mediocrity. Really, none of his great triumphs come down to his great deeds, he just manages to be in the right place at the right time – and by the end of the story, he’s canny enough to work with that. By the end of the story, Giles is simply able to use the tools at hand to put himself in ‘the right place’ (namely, the bridge to Ham) and be successful.

But until then, it is very easy to imagine Giles as being ill at ease, a man of little merit in comical armour on an old mare riding in the company of mail-clad knights on mighty stallions. It isn’t until Giles sees for himself that, for all their armour and gear, the knights possess just as much (or little, or less) merit as he does that he’s able to come into his own.

It’s not necessarily a conventional reading of this simple story, but I quite like it – and I daresay it might hold some truth for anyone who’s ever experienced the dreadful spectre of impostor syndrome. Giles both does and doesn’t belong among the king’s knights – his poor appearance, of course, heightens his lack of ‘belonging’, makes it fully apparent that he doesn’t ‘deserve’ to be there. For anyone who’s ever gained a place studying in some long-desired institution, or who has been appointed to a position beyond anything they’ve ever achieved before, I do think that they’ll have felt similarly out of place – I know I have, several times.

Further, Giles’ bravery and intelligence does actually make him the equal (or better) to any of the knights, but until this is explicitly proven to him, he has every reason to be uncomfortable among their company. Or to put it another way, Giles does indeed deserve his place of honour, the story makes this explicit – he just doesn’t believe it.

To bring this entire post full circle, Giles is not just a reflection upon impostor syndrome, he’s also Tolkien’s thesis concerning just how an ‘ideal’ king might come to power. The tragedy of Tolkien’s ideal king as outlined in the opening quote is that such a person would not seek glory and dominion in the first place – their perfectly suited nature toward kinghood is also what bars them from wanting to be a monarch in the first place.

In Giles’ case, there is never any sign that he actually wants to be King at all – again, he just happens to be in the right place. And, once he comes to accept his own competency (and has the incompetence of all the King’s knights and, by extension, the King himself demonstrated to him), he transforms from doubt to certainty. Yet even then, he doesn’t seem to ‘seek’ power as such, rather accepting power as it is bestowed upon him by the adoring countryside.

A recurring trope of Tolkien’s works is that of the Unlikely (or Unexpected) Hero. Frodo and Sam are unlikely heroes. Bilbo is not only unlikely, but delightfully and improbably incongruous. Even the “great” heroes of the First Age usually rise far above their station and means in achieving their victories – Beren defies Morgoth, and Eärendil brings hope unlocked-for. And of course, last week’s post was dedicated to the littleness of Niggle – yet even Niggle is heroic, if in his own small way.

(As an aside, Tolkien also takes a curious (if logical) delight in deconstructing the “Likely” Hero…I’ve previously written about Thorin and how he fits this mould, but Túrin and Fëanor are other examples of this tendency.)

However, of all Tolkien’s heroes, few can be unlikelier – or eventually rise to greater stature – than Farmer Giles of Ham, the mock-hero of the mock-tale. But I think there’s something worthwhile to examine there nonetheless, precisely because of Giles’ idealised world and nature. Giles really is Tolkien’s ideal king in many ways – perhaps not a ‘perfect’ king, but near as good as can be got as earthly kings go.

And a large part of Giles’ idealness to rule comes down to Giles’ own insecurity and uncertainty throughout the greater part of the story. Giles is not cowardly or timid, but he is keenly aware of how ill-suited he is to be a hero, a trait which makes him very relatable indeed. But, at the same time, Giles also possesses the wisdom to not become bogged down in these concerns, to accept greatness when it is thrust upon him (whilst not himself becoming ‘Great’). We could all stand to learn a bit from Farmer Giles, I think – Tolkien’s least-deserving hero, who nonetheless deserves his victories every bit as much as anyone else.

It must be admitted that Giles owed his rise in a large measure to luck, though he showed some wits in the use of it.

If Giles is Tolkien’s ‘impostorish’ character, then he’s also Tolkien’s guide to rising beyond the fears of impostor syndrome. Because if all Giles needs to do is to be in the right place at the right time – well, surely that’s all that can be expected of us, too? Giles might seem like an imposter, might stick out like a sore thumb, but ultimately he proves himself the measure of any knight. This really isn’t a self-help blog (blegh) but, next time you find yourself in a company of ‘betters’, feeling like a peasant among knights, be like Giles. Put aside your doubts, keep your wits about you, and work with the luck you’ve got (after all, you must have some to be in this situation in the first place!) and…well, you might not kill the dragon in the end.

But you stand a very fair chance of claiming a good part of the dragon’s treasure at least.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Thanks for reading – feel free to check out anything else you may be interested in on the blog, there’s plenty more to discover! Follow me on Facebook and on Twitter to stay up to date with The Blog of Mazarbul, and if you want to join in the discussion, write a comment below or send an email. Finally, if you really enjoyed the post above, you can support the blog via Paypal, and keep The Blog of Mazarbul running. Thanks for reading, and may your beards never grow thin!