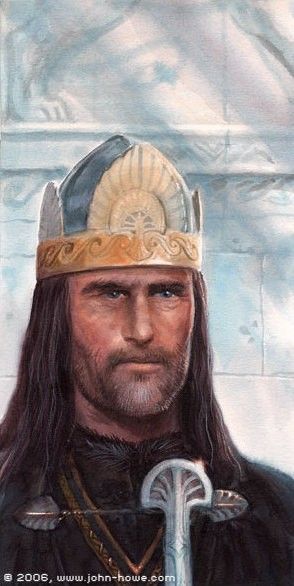

Something that’s long struck me as being worthy of investigation and consideration is the subtle and quiet character journey that Aragorn undergoes throughout The Lord of the Rings.

It’s something I might dip into a few times this year, as (despite the not infrequent criticisms that he is a flat and uninteresting character in the books) I truly believe there is much of merit to be gleaned. Aragorn may seldom serve as the point of view character, and is undeniably already fully realised as a hero when he meets the hobbits in Bree…yet he does have an arc, I think.

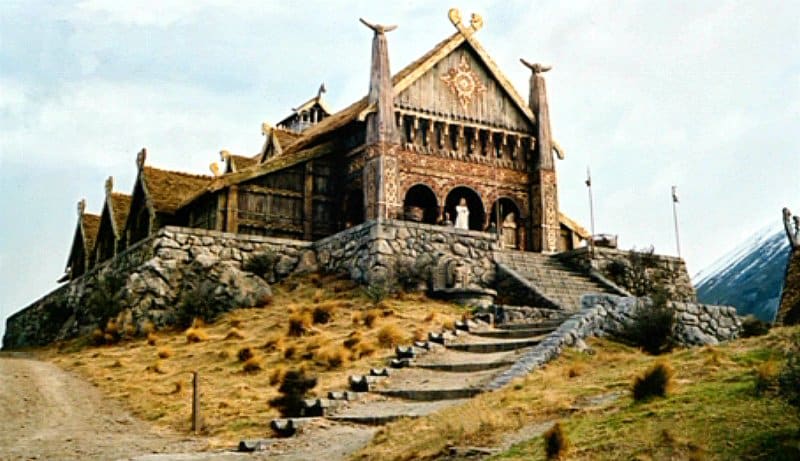

One of the clearest (if near-wholly de-emphasised) examples of this development may be observed when Aragorn comes to Meduseld. As he and his companions approach the Golden Hall, they are halted first by a guard at the gates.

‘Strange names you give indeed! But I will report them as you bid, and learn my master’s will,’ said the guard. ‘Wait here a little while, and I will bring you such answer as seems good to him. Do not hope too much! These are dark days.’ He went swiftly away, leaving the strangers in the watchful keeping of his comrades.

After some time he returned. ‘Follow me!’ he said. ‘Théoden gives you leave to enter; but any weapon that you bear, be it only a staff, you must leave on the threshold. The doorwardens will keep them.’

The Lord of the Rings, Book III, Chapter 6, ‘The King of the Golden Hall’, by J.R.R. Tolkien

There is, at the time, no further conversation or question concerning this rather clear instruction from the guard; and Aragorn thus has plenty of time to mull it over as he is escorted to the doors of Meduseld, where the rather diverse reactions of each traveller are (I think) extremely revealing. Legolas, it would seem, has no quarrel with the request.

‘I am the Doorward of Théoden,’ he said. ‘Háma is my name. Here I must bid you lay aside your weapons before you enter.’

Then Legolas gave into his hand his silver-hafted knife, his quiver, and his bow. ‘Keep these well,’ he said, ‘for they come from the Golden Wood and the Lady of Lothlórien gave them to me.’

Wonder came into the man’s eyes, and he laid the weapons hastily by the wall, as if he feared to handle them. ‘No man will touch them, I promise you,’ he said.

LOTR, Book III, Chapter 6

Yet Aragorn is rather more reticent in giving up his blade.

Aragorn stood a while hesitating. ‘It is not my will,’ he said, ‘to put aside my sword or to deliver Andúril to the hand of any other man.’

‘It is the will of Théoden,’ said Háma.

‘It is not clear to me that the will of Théoden son of Thengel, even though he be lord of the Mark, should prevail over the will of Aragorn son of Arathorn, Elendil’s heir of Gondor.’

‘This is the house of Théoden, not of Aragorn, even were he King of Gondor in the seat of Denethor,’ said Háma, stepping swiftly before the doors and barring the way. His sword was now in his hand and the point towards the strangers.

LOTR, Book III, Chapter 6

Disaster, clearly, is assured – and I have on occasion heard others say that they think rather poorly of Aragorn in this moment; that he comes across less as a noble king-to-be and rather more as a stubborn and needlessly arrogant braggart. It is true, he is indeed Elendil’s heir – and yet as of this moment he has not been recognised as such by Minas Tirith, by the North, or by anyone of note. Further, Háma is entirely in the right – no matter Aragorn’s station, he is now come before the house of Théoden, and it is Théoden who governs this place.

So far, so good, and this is all extremely surface level reading. But the next couple of passages are (I think) rather more revealing, as Gandalf makes to interject and to correct things…and, despite Gandalf’s great friendship with Aragorn, the wizard takes Háma’s side and (gently) challenges Aragorn. Even so, though, Aragorn initially refuses to back down (and is supported by the ever-loyal Gimli).

‘This is idle talk,’ said Gandalf. ‘Needless is Théoden’s demand, but it is useless to refuse. A king will have his way in his own hall, be it folly or wisdom.’

‘Truly,’ said Aragorn. ‘And I would do as the master of the house bade me, were this only a woodman’s cot, if I bore now any sword but Andúril.’

‘Whatever its name may be,’ said Háma, ‘here you shall lay it, if you would not fight alone against all the men in Edoras.’

‘Not alone!’ said Gimli, fingering the blade of his axe, and looking darkly up at the guard, as if he were a young tree that Gimli had a mind to fell. ‘Not alone!’

LOTR, Book III, Chapter 6

Gandalf again intercedes, and now Aragorn finally pays heed to his friend (and is swiftly followed by Gimli, who seemingly has no great quarrel with the demand himself).

‘Come, come!’ said Gandalf. ‘We are all friends here. Or should be; for the laughter of Mordor will be our only reward, if we quarrel. My errand is pressing. Here at least is my sword, goodman Háma. Keep it well. Glamdring it is called, for the Elves made it long ago. Now let me pass. Come, Aragorn!’

Slowly Aragorn unbuckled his belt and himself set his sword upright against the wall. ‘Here I set it,’ he said; ‘but I command you not to touch it, nor to permit any other to lay hand on it. In this Elvish sheath dwells the Blade that was Broken and has been made again. Telchar first wrought it in the deeps of time. Death shall come to any man that draws Elendil’s sword save Elendil’s heir.’

The guard stepped back and looked with amazement on Aragorn. ‘It seems that you are come on the wings of song out of the forgotten days,’ he said. ‘It shall be, lord, as you command.’

‘Well,’ said Gimli, ‘if it has Andúril to keep it company, my axe may stay here, too, without shame’; and he laid it on the floor. ‘Now then, if all is as you wish, let us go and speak with your master.’

LOTR, Book III, Chapter 6

What, to me, is intriguing here is how Aragorn initially presents himself – haughty, proud, a king returned unto his realm. There is an air of the epic, the heroic about him – now is his hour, the moment when his claim to the throne will be realised (or, at the worst, will suffer glorious defeat). And so he elects to carry himself so – only to be thwarted at the first moment by an obstinate warden. Aragorn and Háma believe themselves to be in very different tales, yet find themselves suddenly on the same page.

If this idea is sounding at all familiar to you, then you’ve read too much of my blog – because it is precisely this exact trap that I have previously argued Thorin Oakenshield fell into. Thorin, too, was blinded by the pride of his glorious “destiny,” of realising his heroic fate.

Yet of course, the difference is that Thorin did not realise the error of his pride until it was far, far too late. Aragorn, by comparison, initially doubles down – only to be reprimanded by Gandalf (as, indeed, Thorin was on several occasions too) and to subsequently alter his behaviour.

This is, I think, especially striking when the remainder of the passage above is quoted, as Gandalf infamously protests the confiscation of his staff, not moments after encouraging Aragorn to do as Théoden bids.

The guard still hesitated. ‘Your staff,’ he said to Gandalf. ‘Forgive me, but that too must be left at the doors.’

‘Foolishness!’ said Gandalf. ‘ Prudence is one thing, but discourtesy is another. I am old. If I may not lean on my stick as I go, then I will sit out here, until it pleases Théoden to hobble out himself to speak with me.’

Aragorn laughed. ‘Every man has something too dear to trust to another. But would you part an old man from his support? Come, will you not let us enter?’

‘The staff in the hand of a wizard may be more than a prop for age,’ said Háma. He looked hard at the ash-staff on which Gandalf leaned. ‘Yet in doubt a man of worth will trust to his own wisdom. I believe you are friends and folk worthy of honour, who have no evil purpose. You may go in.’

LOTR, Book III, Chapter 6

It would be all too easy for Aragorn to rebuke Gandalf as he himself was rebuked, yet he does not. Aragorn’s trust in Gandalf’s counsel is ultimately greater than either his pride or his own wisdom.

Strangely, there is a (to my mind) strikingly similar passage in the previous book, as the Fellowship is escorted into Lothlórien by Haldir, and the Elves demand that the Dwarf be escorted blindfolded.

Gimli drew his axe from his belt. Haldir and his companion bent their bows. ‘A plague on Dwarves and their stiff necks!’ said Legolas.

‘Come!’ said Aragorn. ‘If I am still to lead this Company, you must do as I bid. It is hard upon the Dwarf to be thus singled out. We will all be blindfold, even Legolas. That will be best, though it will make the journey slow and dull.’

Gimli laughed suddenly. ‘A merry troop of fools we shall look! Will Haldir lead us all on a string, like many blind beggars with one dog? But I will be content, if only Legolas here shares my blindness.’

‘I am an Elf and a kinsman here,’ said Legolas, becoming angry in his turn.

‘Now let us cry: “a plague on the stiff necks of Elves!” ’ said Aragorn. ‘But the Company shall all fare alike. Come, bind our eyes, Haldir!’

LOTR, Book II, Chapter 6, ‘Lothlórien’

The similarities between the Lórien and the Meduseld passage are, I think, clear. What is rather more interesting to me are the differences, given those similarities. For one thing, the role that Aragorn takes on is obviously different in each – with the Elves, he acts as mediator and intercessor, whereas in Rohan he takes on the “aggrieved party” role previously held by Gimli.

Yet the subtler distinction is also the more interesting one, I think. In Lórien, Aragorn both gently mocks Legolas (the Elf fulfilling the “hypocrite” role, if you will), and sides with the Galadhrim, actively seeking a solution that he knows they will find agreeable (though it goes against the desires of Aragorn’s own companions). In Rohan, the “hypocrite” is Gandalf – one moment encouraging Aragorn to surrender his sword, the next obstinately clutching his own staff. And if anything, Aragorn thus has every reason to be doubly aggrieved with Gandalf for his stubbornness, every reason to turn the tables on Gandalf as he did to Legolas in the Golden Wood.

And Aragorn…doesn’t. He laughingly remarks upon Gandalf’s double standard, but he does not press it, and actively implores Háma to allow Gandalf his staff. Aragorn, in short, is doubly trusting in Gandalf’s judgement here, and deferring to it, despite his own kingly stirrings. We know that Aragorn is not afraid to call out this hypocrisy, so clearly he does not see it as hypocrisy but trusts it to be wisdom…a trust that is rewarded as Gandalf heals Théoden.

It’s a really small moment, and yet (I believe) terribly revealing. Aragorn, like Thorin, is a king coming into his kingdom, and is self-aware and proud of it. Yet Aragorn, unlike Thorin, is able to recognise when (and when not) to rely upon those narrative trappings and inclinations. Unlike Thorin, Aragorn is willing to adjust and alter his behaviour when counselled to. And unlike Thorin, Aragorn accedes with good grace, even to the point of defending Gandalf…because Aragorn trusts that Gandalf is not falling prey to the same proud feelings that he himself (and Gimli and Legolas before in Lothlórien) had felt.

Now, if the Meduseld incident were the end of it, that would perhaps not be a very compelling arc. Yet it is not – because much, much later in the story, Aragorn finally comes into his own, finally has the chance to declare himself and his birthright before Minas Tirith. And he does not. In this moment, despite the earlier arrogance at Meduseld, Aragorn chooses humility and prudence over pride and brashness.

Now as the sun went down Aragorn and Éomer and Imrahil drew near the City with their captains and knights; and when they came before the Gate Aragorn said:

‘Behold the Sun setting in a great fire! It is a sign of the end and fall of many things, and a change in the tides of the world. But this City and realm has rested in the charge of the Stewards for many long years, and I fear that if I enter it unbidden, then doubt and debate may arise, which should not be while this war is fought. I will not enter in, nor make any claim, until it be seen whether we or Mordor shall prevail. Men shall pitch my tents upon the field, and here I will await the welcome of the Lord of the City.’

But Éomer said: ‘Already you have raised the banner of the Kings and displayed the tokens of Elendil’s House. Will you suffer these to be challenged?’

‘No,’ said Aragorn. ‘But I deem the time unripe; and I have no mind for strife except with our Enemy and his servants.’

And the Prince Imrahil said: ‘Your words, lord, are wise, if one who is a kinsman of the Lord Denethor may counsel you in this matter. He is strong- willed and proud, but old; and his mood has been strange since his son was stricken down. Yet I would not have you remain like a beggar at the door.’

‘Not a beggar,’ said Aragorn. ‘Say a captain of the Rangers, who are unused to cities and houses of stone.’ And he commanded that his banner should be furled; and he did off the Star of the North Kingdom and gave it to the keeping of the sons of Elrond.

LOTR, Book V, Chapter 6, ‘The Battle of the Pelennor Fields’

The contrast between Aragorn here and the petulant Aragorn of Rohan is striking. To be sure, the passages are not identical, Imrahil is not asking Aragorn to surrender his precious sword! Yet before the gates of Meduseld in Rohan, Aragorn was stubborn, proud, unwilling to surrender claim to his heritage. Here, on the field of victory (a victory that in large part belongs to him), before the very city that he actually has claim over, he is refusing to press it, refusing to make any sort of move upon the throne…or anything that might even be construed as a move. He is, in a word, displaying discretion.

Aragorn in Rohan was wilful, stubborn, presumptuous – and now he is cautious and humble, though not to the point of sacrificing his pride. Rather, Aragorn’s displaying a little political acumen here (as well as prudence in not wishing to distract his allies from the true priority of confronting Sauron); acumen and prudence that were both sorely lacking outside Meduseld.

I’ve previously argued that Thorin represents Tolkien’s examination and deconstruction of the “heroic king;” that Thorin can be read as a study in the weaknesses of such a character. It is, I think, less controversial to read Aragorn as being born of that same heroic mould…but Aragorn is not just a medieval hero; he is a medieval hero reconstructed. A character who represents those ancient ideals and tropes that Tolkien loved, yet also with the wit and the wisdom to steer aside from making the same blunders that Thorin was ensnared by…and I think such a reading is supported by Aragorn learning that wisdom through his error at Meduseld.

Aragorn, in that moment, comes perilously close to falling, and it is only due to the cautions of Gandalf and Aragorn’s own humility that he accedes to Háma’s request. Yet in acceding, and doing so with good grace, Aragorn learns a crucial lesson concerning the need to respect political, as well as heroic, ideals. When Aragorn later refuses to enter Minas Tirith, he does not yet know that Denethor (a prouder and sterner lord than Théoden) is dead – and in the end, Aragorn’s claim is recognised near-immediately by Imrahil, by the new Steward Faramir, and by anyone else worth anything.

But even after learning of Denethor’s passing, Aragorn enters the city only unwillingly and in secret, refusing to announce his presence (and ironically, it is Gandalf himself once again who “meddles;” encouraging Aragorn to come and seeming to anticipate that Ioreth will spread the word that the King is returned more effectively than any herald!). And as the Host of the West marches upon Mordor, Aragorn still refuses to himself claim the title of King – though he does not seem to oppose the title being bestowed upon him.

Then Aragorn set trumpeters at each of the four roads that ran into the ring of trees, and they blew a great fanfare, and the heralds cried aloud: ‘The Lords of Gondor have returned and all this land that is theirs they take back.’ The hideous orc-head that was set upon the carven figure was cast down and broken in pieces, and the old king’s head was raised and set in its place once more, still crowned with white and golden flowers; and men laboured to wash and pare away all the foul scrawls that orcs had put upon the stone.

…

Ever and anon Gandalf let blow the trumpets, and the heralds would cry: ‘The Lords of Gondor are come! Let all leave this land or yield them up!’ But Imrahil said: ‘Say not The Lords of Gondor. Say The King Elessar. For that is true, even though he has not yet sat upon the throne; and it will give the Enemy more thought, if the heralds use that name.’ And thereafter thrice a day the heralds proclaimed the coming of the King Elessar.

LOTR, Book V, Chapter 10, ‘The Black Gate Opens’

It is fascinating to me, the reconciling of the brash and self-assured Aragorn in Edoras with the prudent and cautious King returned to his realm. And Tolkien never draws a connection between the two passages, there is no moment of internal monologuing on Aragorn’s part concerning the humility counselled by Gandalf. Yet I cannot help but feel that there is a connection; that Aragorn experiences a sudden moment of character growth and realisation outside Meduseld. And I truly think that it’s illustrative of Aragorn’s character and role as ambitioned by Tolkien – he is not merely an archetypal and stereotypical mediaeval hero, but one reconstructed and reimagined; a mediaeval hero who does not sacrifice his northern spirit yet who is capable of engaging in political and empathetic thought.

I’ve previously argued that there is a degree of self-awareness to Thorin’s character, and I am sure that the same is true of Aragorn (Aragorn’s own referring to the Tale of Tinúviel is strong evidence of this). Aragorn, like Thorin, ‘knows’ what sort of story he is in, and ‘knows’ what character he is. Yet unlike Thorin, Aragorn is able to see beyond this manifest heroic destiny. Aragorn is willing to bow to the counsel and wishes of others, and this ironically allows him to succeed in realising that destiny where Thorin failed.

But Aragorn has to learn this lesson, has to learn that though his hour is come, this does not grant him authority or ability to simply ‘become king.’ And he learns that lesson outside the Golden Hall, challenged by a simple doorwarden realising the will of a dotard and impolite king. Outside Meduseld, Aragorn attempts and fails to wield authority – yet through this subversion and deconstruction, he becomes a better king and a better person. Yes, Aragorn comes off poorly by Théoden’s door, but that is not the point of this passage. The point is that Aragorn learns wisdom through his mistake; and that misjudgement and correction on Aragorn’s part is to me a powerful and interesting moment of development (however deemphasised) of his very character.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Thanks for reading – feel free to check out anything else you may be interested in on the blog, there’s plenty more to discover! Follow me on Facebook and on Twitter to stay up to date with The Blog of Mazarbul, and if you want to join in the discussion, write a comment below or send an email. Finally, if you really enjoyed the post above, you can support the blog via Paypal, and keep The Blog of Mazarbul running. Thanks for reading, and may your beards never grow thin!