This is a relatively minor observation, but I’ve been fascinated for some time by Aragorn’s surprisingly clear self-delineation between “himself” and “Strider”. It is a relatively simple thing to see “Strider” as being but another alias for the Ranger, and it’s often treated as such by commenters on the story. Yet a close reading of how Aragorn himself speaks of Strider creates a strong impression (to me, at least) that Aragorn sees Strider as being a character…at least initially.

Arguably, the most memorable indication of this separation comes during Aragorn’s rebuke to Boromir at the Council of Elrond, in which he speaks of the dreadful evils that the Rangers of the North watch against:

‘Peace and freedom, do you say? The North would have known them little but for us….And yet less thanks have we than you. Travellers scowl at us, and countrymen give us scornful names. “Strider” I am to one fat man who lives within a day’s march of foes that would freeze his heart, or lay his little town in ruin, if he were not guarded ceaselessly.’

The Lord of the Rings, Book II, Chapter 2, ‘The Council of Elrond’, by J.R.R. Tolkien

However, it is generally Aragorn’s earlier treatment of the name that I find compelling, especially in the appropriately-titled chapter “Strider” in Book I. Here, several times, as Aragorn speaks to the hobbits, he slips into a curious third-person perspective, as if he is not talking of himself but of another person (or a character) who goes by “Strider.”

‘There!’ he cried after a moment, drawing his hand across his brow. ‘Perhaps I know more about these pursuers than you do. You fear them, but you do not fear them enough, yet. Tomorrow you will have to escape, if you can. Strider can take you by paths that are seldom trodden. Will you have him?’

…

‘These black men,’ said the landlord lowering his voice. ‘They’re looking for Baggins, and if they mean well, then I’m a hobbit….And that Ranger, Strider, he’s been asking questions, too. Tried to get in here to see you, before you’d had bite or sup, he did.’

‘He did!’ said Strider suddenly, coming forward into the light. ‘And much trouble would have been saved, if you had let him in, Barliman.’

…

‘It would take more than a few days, or weeks, or years, of wandering in the Wild to make you look like Strider,’ he answered.

…

‘Well,’ said Strider, ‘with Sam’s permission we will call that settled. Strider shall be your guide.‘

The Lord of the Rings, Book I, Chapter 10, ‘Strider’, by J.R.R. Tolkien

Tolkien occasionally has characters name or refer to themselves in the third person, a literary technique known as illeism. Indeed, two of the book’s most distinctively-voiced characters are notable for being inveterate illeists – Tom Bombadil, and Gollum. In the case of the latter, the illeisms serve to illustrate Gollum’s broken and fractured nature, and may even lend to his tragic simpleness. With Tom, it is impossible not to feel as if he chiefly enjoys the sound of his own name! But here, too, there is (I think) something of a simplicity lent to the character, but unlike Gollum’s broken mind, Tom’s simplicity is oriented toward making him seem wholly natural, and wholly self-assured.

Yet other characters, too, call upon illeism, if less frequently than Tom and Gollum. Gandalf, Galadriel and Saruman, for example, infrequently employ it, generally as a rhetorical device to lend their words weight and effect. I suspect Aragorn also uses such devices from time to time with his right name, and others, but searching for such occurrences is difficult! Nonetheless, the point stands – it is not a wholly alien technique in LOTR.

Even so, though, the frequency with which Aragorn refers to “Strider” in the third person when he meets the hobbits remains striking to me. Nowhere else, to the best of my knowledge, does a character employ such consistent illeisms (with the above-mentioned exceptions of Tom and Gollum, who are themselves highly atypical figures) in the story.

And while one could read “Strider” as trying to employ some sort of loftiness in winning the trust of the hobbits, I’m rather tempted to read it rather as being an example of “Strider” really being a character that Aragorn employs…a facet of himself, as it were, that is neither false nor fully true, but feigned and put on for the sake of Bree (and other such Northern towns).

The dismissiveness with which Aragorn mentions “Strider” at Rivendell is one piece of evidence in support of this idea. But the text itself also makes occasional reference to Aragorn casting aside that Ranger persona, or revealing his true nature, most memorably when he beholds the Argonath upon the Anduin.

‘Fear not!’ said a strange voice behind him. Frodo turned and saw Strider, and yet not Strider; for the weatherworn Ranger was no longer there. In the stern sat Aragorn son of Arathorn, proud and erect, guiding the boat with skilful strokes; his hood was cast back, and his dark hair was blowing in the wind, a light was in his eyes: a king returning from exile to his own land.

The Lord of the Rings, Book II, Chapter 9, ‘The Great River’, by J.R.R. Tolkien

However, there’s also a fascinating consistency with the specific manner with which Aragorn introduces himself as “Strider.” Consider his very first words to Frodo, when he introduces himself at the Prancing Pony.

As Frodo drew near he threw back his hood, showing a shaggy head of dark hair flecked with grey, and in a pale stern face a pair of keen grey eyes.

‘I am called Strider,’ he said in a low voice. ‘I am very pleased to meet you, Master – Underhill, if old Butterbur got your name right.’

The Lord of the Rings, Book I, Chapter 9, ‘At the Sign of the Prancing Pony’, by J.R.R. Tolkien

I am called Strider. Not “my name is Strider,” or, “I am Strider.” Called. I.e., other people use this name of him…it is not necessarily his own name (as, indeed, we soon learn it is not).

This may seem like a reach on my part, but given Tolkien’s notoriety for clarity and precision in language, it is at least worth pursuing. And indeed, Aragorn introduces himself as “Strider” twice more in the text – and both times, he uses the same precise wording. The next time occurs in the following chapter, when Pippin and Sam are introduced to the sinister Ranger.

‘Hallo!’ said Pippin. ‘Who are you, and what do you want?’

‘I am called Strider,’ he answered; ‘and though he may have forgotten it, your friend promised to have a quiet talk with me.’

LOTR, Book I, Chapter 10

Later in the chapter, following the delivery of Gandalf’s letter (in which Aragorn is named) and Strider’s words that reveal that he knows rather more of their Quest than the hobbits might ever have guessed, he names himself as Aragorn…and this time, he no longer says “called.”

‘But I am the real Strider, fortunately,’ he said, looking down at them with his face softened by a sudden smile. ‘I am Aragorn son of Arathorn; and if by life or death I can save you, I will.’

LOTR, Book I, Chapter 10

And, bringing both these themes together (Aragorn’s choice of words and his treating of Strider as a character and a cloak), a full two books later, he uses the Strider name again, now far from Bree and frightened hobbits, on the plains of Rohan. And, when he reveals his true identity later in the conversation, he again loses the “called”…and his companions again register an alteration in him.

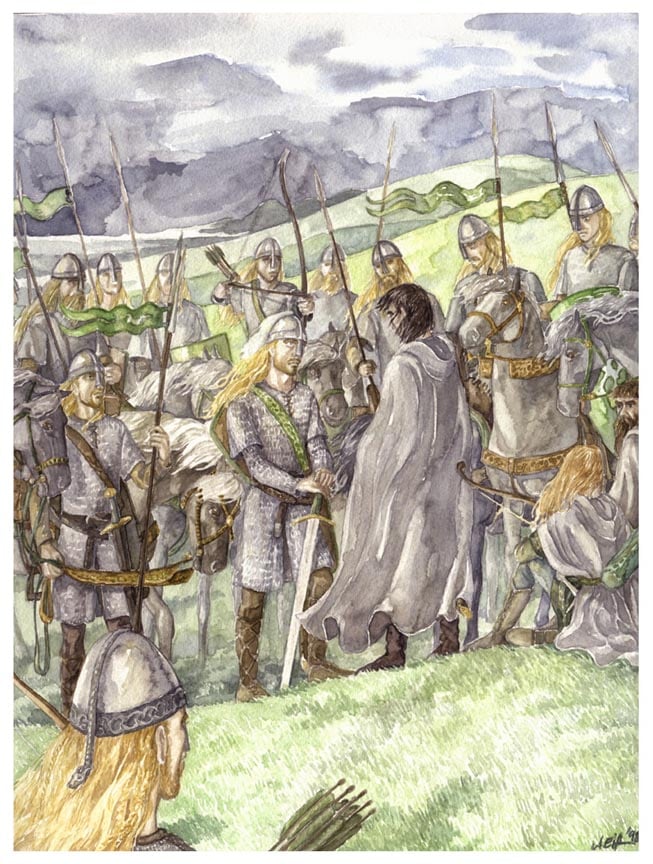

‘Who are you, and what are you doing in this land?’ said the Rider, using the Common Speech of the West, in manner and tone like to the speech of Boromir, Man of Gondor.

‘I am called Strider,’ answered Aragorn. ‘I came out of the North. I am hunting Orcs.’

…

Aragorn threw back his cloak. The elven-sheath glittered as he grasped it, and the bright blade of Andúril shone like a sudden flame as he swept it out. ‘Elendil!’ he cried. ‘I am Aragorn son of Arathorn, and am called Elessar, the Elfstone, Dúnadan, the heir of Isildur Elendil’s son of Gondor. Here is the Sword that was Broken and is forged again! Will you aid me or thwart me? Choose swiftly!’

Gimli and Legolas looked at their companion in amazement, for they had not seen him in this mood before. He seemed to have grown in stature while Éomer had shrunk; and in his living face they caught a brief vision of the power and majesty of the kings of stone. For a moment it seemed to the eyes of Legolas that a white flame flickered on the brows of Aragorn like a shining crown.

The Lord of the Rings, Book III, Chapter 2, ‘The Riders of Rohan’, by J.R.R. Tolkien

This transformation of Aragorn is undoubtedly a moment of ennobling for the character, as it is usually read – a moment of high heroism, as the King returns and claims his right. But I do not think it is unreasonable to see it as also being at least somewhat deliberate on Aragorn’s part, an unmasking or revealing as he allows the ragged Ranger Strider to withdraw.

Yet it also remains important to note that while “Strider” is not Aragorn, he is not not Aragorn either. Strider is not a character played by Aragorn, but a character drawn from him, an aspect of him that he employs at need. In other words, there is no “falsehood” about Strider’s being…though one could argue that there is a lie of omission in him.

‘Now let us take our ease here for a little!’ said Aragorn. ‘We will sit on the edge of ruin and talk, as Gandalf says, while he is busy elsewhere. I feel a weariness such as I have seldom felt before.’ He wrapped his grey cloak about him, hiding his mail-shirt, and stretched out his long legs. Then he lay back and sent from his lips a thin stream of smoke.

‘Look!’ said Pippin. ‘Strider the Ranger has come back!’

‘He has never been away,’ said Aragorn. ‘I am Strider and Dúna-dan too, and I belong both to Gondor and the North.’

The Lord of the Rings, Book III, Chapter 9, ‘Flotsam and Jetsam’, by J.R.R. Tolkien

Aragorn’s consistent and careful delineation of “Strider” shouldn’t be read as Strider being a separate psychological entity (as some have posited may be the case with Gollum), nor as being something he puts upon himself (as one could arguably see in Tom Bombadil). There is a deliberateness, though, to Aragorn not fully identifying as Strider, and I think that’s fascinating. It seems clear to me that there is an element of choice in it, that Aragorn chooses to play the part of Strider when it suits him (as he initially does in both Bree and Rohan). And I think it’s really interesting to note how he employs illeism – whether consciously or subconsciously – while the role of Strider is upon him.

As a final note, I did a cursory examination of Tolkien’s draft versions in the parallel passages. Trotter (as this proto-Aragorn hobbit was known) does not, in his first appearance, match “Strider’s” distinctive delineation. However, later in the passage, he does employ an illeism in the same manner as in the published version.

Bingo found Trotter looking at him, as if he had heard or guessed all that was said. Presently the Ranger, with a click and a jerk of his hand, invited Bingo to come over to him; and as Bingo sat down beside him he threw back his hood, showing a long shaggy head of hair, some of which hung over his forehead. But it did not hide a pair of keen dark eyes. ‘I’m Trotter,’ he said in a low voice. ‘I am very pleased to meet you, Mr — Hill, if old Barnabas had your name right?’

The Return of the Shadow, VIII, Arrival at Bree, by J.R.R. Tolkien, ed. Christopher Tolkien

‘There! It has passed!’ he said after a moment, throwing back his hood and pushing his hair from his face. ‘Perhaps I know or guess more about these Riders then even you do. You do not fear them enough – yet. But it seems likely enough to me that news of you will reach them before the night is old. Tomorrow you will have to go swiftly and secretly (if possible). But Trotter can take you by ways that are little trod. Will you have him?’

The Return of the Shadow, IX, Trotter and the Journey to Weathertop, by J.R.R. Tolkien, ed. Christopher Tolkien

Here, I must assume that the illeism is intended to serve as a rhetorical emphasis, and not to have any sort of delineation. But even as the character of Trotter was being developed, Tolkien was establishing that this was an alias, and as Christopher Tolkien observes:

In Frodo’s first conversation with Trotter, and in all that follows to the end of Chapter 9 in FR, the present text moves almost to the final form (which has in any case been virtually attained, in the latter part, already in the original version…)

The Return of the Shadow XX The Third Phase (2): At the Sign of the Prancing Pony, by J.R.R. Tolkien, ed. Christopher Tolkien

Hence, it is not unreasonable to suspect that even as Trotter materialised, Tolkien was considering these questions of identity and how Trotter viewed himself, and that he may have leant upon these rather deliberately from an early stage.

And, as Trotter the hobbit diminished and Trotter the man emerged, I think that Tolkien’s very careful linguistic choices also crystalised. For when Trotter/Aragorn meets the Riders of Rohan, we see that Tolkien’s use of the “I am called/I am” distinction was clearly not accidental, by way of his editorialising.

‘Who are you, and what are you doing in this land?’ said the rider, using the common speech of the West, in manner and tone like Boromir and the men of Minas Tirith.

[Rejected immediately: ‘I am Aragorn Elessar (written above: Elfstone) son of Arathorn.] ‘I am called Trotter. I come out of the North,’ he replied, ‘and with me are Legolas [added: Greenleaf] the Elf and Gimli Glóin’s son the Dwarf of Dale. We are hunting orcs. They have taken captive other companions of ours.’

The Treason of Isengard, XX The Riders of Rohan, by J.R.R. Tolkien, ed. Christopher Tolkien

In short, then, I do think there is something deliberate in Tolkien’s consistent choices to create a little self-distance within Aragorn and his persona of “Strider.” And I think there’s something really intriguing and really revealing concerning Aragorn’s character in choosing to take this persona upon himself. It almost seems a mistake to me, to simply ascribe Strider as being an alias of Aragorn’s, when he himself seems to lack this full identification with it. Or, if not a mistake, at least a gross simplification.

Names often seem to bear some significance in Tolkien’s writings. Túrin, infamously, takes on many monikers through his disastrous career, names that often prove ironic or ill-chosen (and are often chosen in turn to avoid some doom or to wallow in it). Dr Sara Brown has recently argued that Éowyn’s assuming of the Dernhelm identity should be seen not merely as a means to an end, but an intriguing and meaningful reflection upon Éowyn’s own identity. Even

In the case of Strider, I personally keep on returning to the idea of Strider being an aspect of Aragorn, and one that he feels distance from. It would not be accurate to say that he is not Strider, and nor would it be reasonable to suggest that he dislikes Strider. But I do wonder whether there isn’t a certain ambivalence toward Strider in Aragorn’s mind, and perhaps even a determination (given the doom laid upon him by Elrond if he is to win Arwen’s hand) to never slip too fully into being Strider.

These are all guesses and musings, of course, and I do not doubt there are other and better readings that might reconcile this Strider/Aragorn delineation. However, the frequent use of illeism in referring to “Strider,” Aragorn’s insistence that he is “called” as such, and his occasional transformations away from the lowly Ranger all build a very compelling picture to me, and I do believe there is something there worthy of further interrogation.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Thanks for reading – feel free to check out anything else you may be interested in on the blog, there’s plenty more to discover! Follow me on Facebook and on Twitter to stay up to date with The Blog of Mazarbul, and if you want to join in the discussion, write a comment below or send an email. Finally, if you really enjoyed the post above, you can support the blog via Paypal, and keep The Blog of Mazarbul running. Thanks for reading, and may your beards never grow thin!