A safe fairy-land is untrue to all worlds.

J.R.R. Tolkien, Letter 17 to Stanley Unwin

The concept of ‘Faerie’ in Tolkien’s writings and philosophy is as important as it is nebulous. It is a state of enchantment, of belief in some secondary reality as guided by a sub-creator – yet it is also that Secondary World itself, and the things that dwell therein. Yet if On Fairy Stories is to be believed, these Faerie tales of Faerie are themselves concerned chiefly with the adventures of men in Faerie – ie, these mortals are themselves less of Faerie than Faerie itself (yet they are nonetheless spun within Faeriean drama).

Tolkien himself is not overly concerned with defining Faerie, writing bluntly that “It cannot be done.” Faerie is a state of being and of thought, it is a magical art, it is a tangible world shimmering on the margins of our own, it is a commitment to Secondary Belief, and it is the home of elves and the sun and the moon and dragons and steam trains and whatever other wonderful things you know of.

In this sense, then, the Shire and the hobbits who dwell therein are assuredly a faerie people. Yet hobbits are also comfortably (and even frustratingly) mortal and human beings As such, exploring their relationship to Faerie is an intriguing challenge, but it is one that I think is worthwhile…and perhaps has not been thoroughly attempted. To be sure, certain notable hobbits and their status within Faerie has been considered – but I’m not so sure that the Shire has been dealt with in the same manner, especially on a cultural and societal level. So that is the challenge of this first post in this series; to consider the Shire and its relationship with Faerie.

In my introduction to this year’s September series, I briefly mentioned Tolkien’s most famed opening line – “In a hole in the ground there lived a hobbit.” It is, of course, a classic and beloved sentence, not least for its delightful contrast between the ordinary (a hole in the ground), the extraordinary (someone living in that hole) and the mysterious (that someone being a hobbit, whatever that might be). As such, it may also seem a good place from which to start in considering hobbits and Faerie – and yet, for the sake of actually understanding what that relationship looks like, I think it rather better for us to skip ahead a couple of paragraphs, as the narrator begins to tell us a little about who hobbits are and how they act.

This hobbit was a very well-to-do hobbit, and his name was Baggins. The Bagginses had lived in the neighbourhood of The Hill for time out of mind, and people considered them very respectable, not only because most of them were rich, but also because they never had any adventures or did anything unexpected: you could tell what a Baggins would say on any question without the bother of asking him. This is a story of how a Baggins had an adventure, and found himself doing and saying things altogether unexpected. He may have lost the neighbours’ respect, but he gained—well, you will see whether he gained anything in the end.

The Hobbit, Chapter I, ‘An Unexpected Party,’ by J.R.R. Tolkien

There are two things to take note of in this passage. One, that whether Bilbo “gained anything in the end” is a matter not of certainty, but to be determined by the reader; implying some degree of interpretation and a need to consider subtext. Naturally, Bilbo does return with some small amount of gained treasure, but the narrator is inviting us to question whether Bilbo’s other ‘gains’ (his wits, his courage, his wisdom, and his joy) are not in fact the titular hobbit’s true winnings, despite their intangibility.

This is of course useful for considering Bilbo, but it still reveals little of hobbits in general. For that task, we must consider the sentence earlier in the paragraph; that the Bagginses were considered “very respectable.” For it is well worth noting that the respectability of the Bagginses is founded in part upon knowing what one “would say on any question without the bother of asking him.” This, again, reveals something striking about the Bagginses (that they are predictable and slightly dull creatures), but it in turn reveals something almost alarming about hobbitish society – that this Bagginsish dullness is itself respectable, something to be striven for and desired. And that, then, is our first real hint at a theme that runs through the entirety of The Hobbit, The Lord of the Rings, and other writings…that the Shire Hobbits are desperately flawed and uncurious beings.

It is a simple and an easy thing to see Tolkien’s Shire as being something of an idealised land. The Jackson films, with the rustic and unspoiled pastoralism that they relish in, are arguably to blame for this being a common reading, but (as I recall) the original sin does not lie with them. It has been common for decades to read the Shire as being an arcadian utopia, an idyllic and idealised land drawn from memories of Tolkien’s own youth and impressions of a rural vanished paradise that (to some degree) perhaps never was.

But such a reading robs the Shire of significant nuance, too. For the Shire is ‘idealised’ only in that it is intentionally gentle and easy, with curious flaws lurking beneath its surface and that ease coming at significant cost. In particular, it is well worth noting that the Shire’s ‘idyllic’ nature is drawn in contrast in many ways with certain ugly tendencies that the idyllic nature not only permits, but encourages.

And if we return to the premise that the opening quote of this post posits – that there is something patently ‘false’ about a fairy-land that is safe – this in turn begs the question: is the Shire, then, truly a fairy-land? Or alternatively, is the Shire rather less safe and idealised than one might imagine? And in a typically annoying Elfish fashion, I suspect the answer may be C, ‘both.’

It is worth interrogating the second possibility first, for it is the easier one to deal with (and one that has been thoroughly dismantled by others already). For while the Shire is undeniably ‘safe’ from an in-universe perspective (in the sense of its being broadly free of orcs, dragons, wraiths, and even wicked Men), it is far from idealised, as Tolkien himself was fully aware.

But hobbits are not a Utopian vision, or recommended as an ideal in their own or any age.

Tolkien, Letter 154 to Naomi Mitchison

The rustic bucolicism and simple life of the Shire hobbits is, Tolkien posits, no good thing in and of itself. Or, more accurately, it is a good thing that can be carried to excess as readily as any other good thing. The Shire hobbits are idle, timid, slow, and deeply suspicious and incurious about anything beyond their lived experience, with Sam Gamgee as a chief (if himself ennobled) example of these tendencies.

Sam is meant to be lovable and laughable. Some readers he irritates and even infuriates. I can well understand it. All hobbits at times affect me in the same way, though I remain very fond of them. But Sam can be very ‘trying’. He is a more representative hobbit than any others that we have to see much of; and he has consequently a stronger ingredient of that quality which even some hobbits found at times hard to bear: a vulgarity — by which I do not mean a mere ‘down-to- earthiness’ — a mental myopia which is proud of itself, a smugness (in varying degrees) and cocksureness, and a readiness to measure and sum up all things from a limited experience, largely enshrined in sententious traditional ‘wisdom’. We only meet exceptional hobbits in close companionship – those who had a grace or gift: a vision of beauty, and a reverence for things nobler than themselves, at war with their rustic self-satisfaction. Imagine Sam without his education by Bilbo and his fascination with things Elvish! Not difficult. The Cotton family and the Gaffer, when the ‘Travellers’ return are a sufficient glimpse.

Tolkien, Letter 246 to Eileen Elgar

And bearing in mind this mental myopia, consider that Sam remains one of the better Hobbits all in all, as illustrated in his discussion with Ted Sandyman.

‘Queer things you do hear these days, to be sure,’ said Sam.

‘Ah,’ said Ted, ‘you do, if you listen. But I can hear fireside-tales and children’s stories at home, if I want to.’

‘No doubt you can,’ retorted Sam, ‘and I daresay there’s more truth in some of them than you reckon. Who invented the stories anyway? Take dragons now.’

‘No thank ’ee,’ said Ted, ‘I won’t. I heard tell of them when I was a youngster, but there’s no call to believe in them now. There’s only one Dragon in Bywater, and that’s Green,’ he said, getting a general laugh.

‘All right,’ said Sam, laughing with the rest. ‘But what about these Tree- men, these giants, as you might call them? They do say that one bigger than a tree was seen up away beyond the North Moors not long back.’

‘Who’s they?’

‘My cousin Hal for one. He works for Mr. Boffin at Overhill and goes up to the Northfarthing for the hunting. He saw one.’

‘Says he did, perhaps. Your Hal’s always saying he’s seen things; and maybe he sees things that ain’t there.’

‘But this one was as big as an elm tree, and walking – walking seven yards to a stride, if it was an inch.’

‘Then I bet it wasn’t an inch. What he saw was an elm tree, as like as not.’

‘But this one was walking , I tell you; and there ain’t no elm tree on the North Moors.’

‘Then Hal can’t have seen one,’ said Ted. There was some laughing and clapping: the audience seemed to think that Ted had scored a point.

The Lord of the Rings, Book I, Chapter 2, ‘The Shadow of the Past,’ by J.R.R. Tolkien

The Shire is not just ordinary, but almost profanely so. This myopia and suspicion concerning things beyond its borders appears over and over again. The Sea is feared, and Gandalf is noted primarily for being a top-notch entertainer and not for his far more difficult and dangerous business. Even their own kind are not spared this hostility, with the ‘queer’ Brandybucks enduring a great deal of unmerited hostility for their dwelling on the wrong side of the River, for messing about with boats, and for knowing a little of the Old Forest. There is a deadly and a stolid conviction in the Shire that the unknown and the alien is to be regarded with suspicion and hostility – and what is Faerie, if it is not the unknown?

But it is Bilbo who is perhaps most instructive in considering that broad Shire myopia. For Bilbo, upon returning from his adventures, is chiefly noted not for any of his great deeds or newfound learning, but for having come into a bit of wealth – for entirely materialistic and superficial reasons. The chief fear of the hobbits that attend his Party is that he will bring in bits of “poetry” (ie, Faerie), and their greatest interest following his disappearance is in what will come of his goods and property (and not where he might have disappeared to, or why.)

And this, then, brings me back around to the first possibility raised above. I think a very good case can be made that the Shire itself is, in some ways (not all) a profoundly anti-Faerie realm, at least when considered on its own terms (I will return in the next post to this question on a different level). And the hobbitish apathy toward what Bilbo calls ‘poetry’ is deeply symptomatic of this anti-Faerie quality that is built into the Shire, and that appears over and over again when it is noticed. For it is not poetry or even prose that the Hobbits favour, as the Prologue to LOTR reveals (emphasis naturally mine):

The genealogical trees at the end of the Red Book of Westmarch are a small book in themselves, and all but Hobbits would find them exceedingly dull. Hobbits delighted in such things, if they were accurate: they liked to have books filled with things that they already knew, set out fair and square with no contradictions.

The Lord of the Rings, Prologue, Part I, ‘Concerning Hobbits’

The hobbits of the Shire consistently demonstrate a profound distaste for and apathy towards the wonder and curiosity of Faerie in every form with which it manifests before them. Dragons are not dragons in the Shire, but pubs. The unconceived is all too readily equated with the impossible. And matters of small doings and local affairs are what capture an ordinary hobbit’s imagination – not Elves or rings or wars.

One summer’s evening an astonishing piece of news reached the Ivy Bush and Green Dragon. Giants and other portents on the borders of the Shire were forgotten for more important matters: Mr. Frodo was selling Bag End, indeed he had already sold it – to the Sackville-Bagginses!

The Lord of the Rings, Book I, Chapter 3, ‘Three is Company’

In some ways, no character encapsulates this un-Faerieishness better than Bilbo Baggins himself, at least as far as he is portrayed throughout The Hobbit. From the beginning, Bilbo is himself presented as being caught between two worlds – his stolid and sensible Baggins inclinations and the inquisitive, daring and explicitly fey Took strain that runs through him.

It was often said (in other families) that long ago one of the Took ancestors must have taken a fairy wife. That was, of course, absurd, but certainly there was still something not entirely hobbitlike about them, and once in a while members of the Took-clan would go and have adventures. They discreetly disappeared, and the family hushed it up; but the fact remained that the Tooks were not as respectable as the Bagginses, though they were undoubtedly richer.

The Hobbit, Chapter I

Corey Olsen, for one, has worked through this reading of Bilbo as being caught between his nice respectable and hobbitish Baggins side and his queer and dangerous Tookish side quite thoroughly in Exploring J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Hobbit, and I would do myself a disservice if I attempted to reiterate his work! But observe in the quote above at least that very final sentence; that the Tooks were not as respectable, but they were richer.

It is impossible to know if Tolkien intended any double-meaning through his choice of wording, but I like to think that he may have. For while the Tooks are ‘richer’ on a plain and material level, as confirmed in other material and notes, I think there is a very real implication that they are richer overall and intangibly, in matters of their knowledge and their inner nobility.

Now, all of these observations – that Hobbits are in many ways myopic and overly parochial – are not overly new. But I think that it is important to link these observations back to Faerie, because it reveals why Hobbitish society is not an ‘ideal’ in any complete sense (though it may be said to achieve certain ideals).

By way of example, it is a relatively common reading of the text to understand the manner in which Saruman dominates the Shire as being symptomatic of this very Hobbitish dullness; that they are too ill-informed and slow to adequately react to the increasing strictures placed upon them by Sharkey, Lotho, and the ruffians in their employ. And to be clear, this is not wholly untrue! Hobbitish naivety and innocence do undoubtedly play a role in permitting Sharkey to seize control without meaningful political opposition.

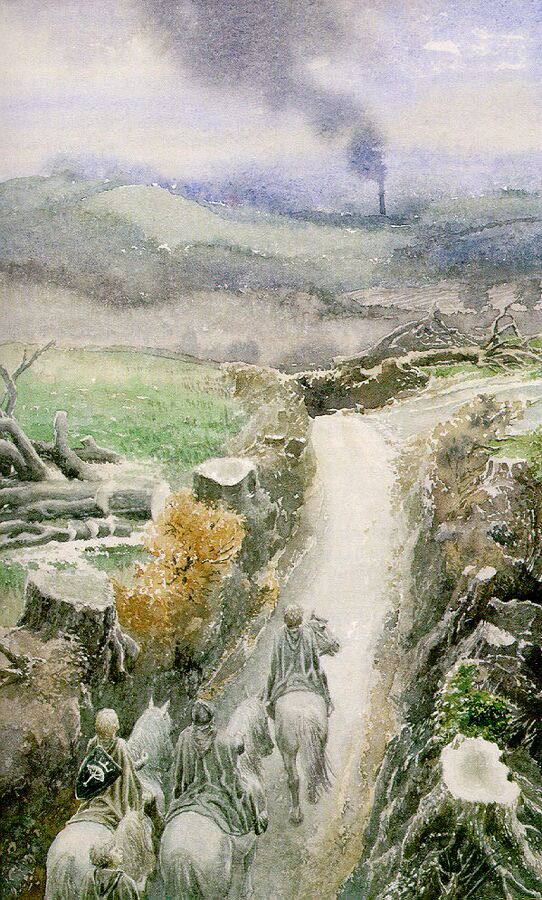

But I think it does not paint the full picture, either. Because in some ways, Saruman’s industrialisation of and control over the Shire is not achieved by Saruman being cleverer than the Hobbits (though he is). It is achieved because Saruman is already oriented to exploit those same Hobbitish flaws of blindly determined apathy. The Shire is beautiful, but its folk do not really realise it. Life there is good, but they do not understand that it is (though they are also convinced that it is better than anywhere else). And so Saruman is able to exert control across the Shire not by imposing his will there, but by ever so slightly directing the will of the Hobbits themselves to their own ruin.

A laugh put an end to them. There was a surly hobbit lounging over the low wall of the mill-yard. He was grimy-faced and black-handed. ‘Don’t ’ee like it, Sam?’ he sneered. ‘But you always was soft. I thought you’d gone off in one o’ them ships you used to prattle about, sailing, sailing. What d’you want to come back for? We’ve work to do in the Shire now.’

‘So I see,’ said Sam. ‘No time for washing, but time for wall-propping. But see here, Master Sandyman, I’ve a score to pay in this village, and don’t you make it any longer with your jeering, or you’ll foot a bill too big for your purse.’

The Lord of the Rings, Book VI, Chapter 8, ‘The Scouring of the Shire’

Ted Sandyman is, of course, an extreme example of a fallen hobbit (though this does not mean he is atypical, merely further gone than most). But note his words, “We’ve work to do in the Shire now.” To Ted, this mechanisation and landscape-scarring brutalisation of the Shire is necessary, because it is work; not for anything that the work actually achieves. And Sam’s response is a perfectly adequate counter to Sandyman’s thought, in that Sam observes work that does need doing being left undone while work that doesn’t is conducted. This, in turn, puts rather a different spin upon Gandalf’s words to the hobbits when he tells them he will not return to the Shire.

‘I am with you at present,’ said Gandalf, ‘but soon I shall not be. I am not coming to the Shire. You must settle its affairs yourselves; that is what you have been trained for. Do you not yet understand? My time is over: it is no longer my task to set things to rights, nor to help folk to do so. And as for you, my dear friends, you will need no help. You are grown up now. Grown indeed very high; among the great you are, and I have no longer any fear at all for any of you.

The Lord of the Rings, Book VI, Chapter 7, ‘Homeward Bound’

It is easy to imagine that Gandalf is referring merely to the strategic acumen amassed by Merry and Pippin (and the stout-hearted love fostered in Sam) through their Quest. And, again, I am sure this is on Gandalf’s mind! But he does not say that the four hobbits have ‘learned’ anything, but that they are ‘grown.’ Grown, I think, in their awareness for and love toward Faerie, and thus well-equipped to see the Shire for what it has become and not to pass over it for what it is.

This is why no hobbit of the Shire could ever really have opposed Saruman’s dreadful work. Because the hobbits themselves are far too blind and dull to ever really see that work for what it is. They might resent it, know on some level that it isn’t right. But they do not possess the moral wisdom to know what degradation it truly is, and they need to be shown it by Faerie-touched folk – and Faerie-touched folk who possess the learning and wits to then enact meaningful change, as Frodo and his friends are.

Or, to put it another way, it is not innocence that makes the Shire vulnerable to Saruman. It is rather the uncreativity and myopic lack of curiosity endemic to the Shire’s people. Saruman tells the Hobbits that there is a better way to manage the Shire, with gathering and sharing and mills and brick houses and thugs, and the Shire hobbits believe him, because their lack of Faerie joy and engagement does not allow them to perceive how dreadful things truly are. They need to be woken up, but their underdeveloped Faeriean wonder is itself a dreadful flaw with or without Saruman. The Shire is not only not a utopia, it is deeply blanded by the love for small and assured certainties and distaste for wonder and question. This, then, is the Shire’s great undoing – that it is not only not Faerie, but it is determinedly and actively unFaerie in whatever fashion it can be.

Having argued that the need for the Scouring of the Shire is brought about by a hobbitish disregard for Faerie, I want to close out this particular post by highlighting another, greater (in potency if not in scope) tragedy that I believe also stems from that hobbit close-mindedness. We have already considered Sam as being an excellent hobbit, but a typical one. But the passage from Letter 246 does not end there, and in fact directly continues.

Sam was cocksure, and deep down a little conceited; but his conceit had been transformed by his devotion to Frodo. He did not think of himself as heroic or even brave, or in any way admirable – except in his service and loyalty to his master. That had an ingredient (probably inevitable) of pride and possessiveness: it is difficult to exclude it from the devotion of those who perform such service. In any case it prevented him from fully understanding the master that he loved, and from following him in his gradual education to the nobility of service to the unlovable and of perception of damaged good in the corrupt. He plainly did not fully understand Frodo’s motives or his distress in the incident of the Forbidden Pool. If he had understood better what was going on between Frodo and Gollum, things might have turned out differently in the end. For me perhaps the most tragic moment in the Tale comes in II 323 ff. when Sam fails to note the complete change in Gollum’s tone and aspect. ‘Nothing, nothing’, said Gollum softly. ‘Nice master!’. His repentance is blighted and all Frodo’s pity is (in a sense) wasted. Shelob’s lair became inevitable.

Letter 246

This blighting of Gollum’s potential repentance by Sam is well-known among Tolkien readers. But I have never before seen it directly considered in light of Sam’s anti-Faerie inclinations. And indeed, why should it be? For Sam is far more Faerie-oriented than many hobbits. He is fascinated by and loves Elves, he listens to Bilbo’s stories and composes his own, he has a proactivity and a knowledge that is matched by few of his fellows.

Yet in Letter 246, Tolkien makes the case that Sam nonetheless remains overly hobbitish in certain respects. Sam’s parochialism remains, his stubbornness and his inability to see beyond himself are not excised. Sam’s ‘ruining’ of Gollum’s possible penitence is rooted in the very same anti-Faerie suppressions that permit Saruman to conquer the Shire without striking a blow. It is Sam’s conceit, his possessiveness, his lack of understanding and his fear of and failure to see to the heart of a Faerie being (which Gollum, for all his pitifulness and dreadfulness, is) that undoes all Gollum’s progress.

In short, it is because Sam is too hobbitish; even Sam is not fully receptive to the joys and sorrows of Faerie, in a manner that is tragically and typically Shireish.

That hobbitish lack of wonder and love for the unknown is, to be clear, a primarily societal issue, I believe – there is nothing in the text that necessarily suggests it is a problem of their kind, merely of their culture. But it is a deeply revealing one too, especially when we recall that hobbits are intended as our point of entry into Middle-earth, and when they are held up as being representative of a certain view of England. The Shire is a good place, make no mistake about it. But it is not the utopia that some imagine it to be, nor is it intended as such by Tolkien. That hobbitish lack of Faerie was, if anything, abhorrent to him, and not without good cause.

In short, that hobbitish parochialism, provincialism, and lack of creative engagement and exploration is not necessarily an issue for the naivety or innocence that it causes in the Shire. It is an issue because it robs hobbits of significant joy and wonder in the world itself. The Shire’s hostility and suspicion towards Faerie in all its manifestations is, ultimately, an indictment of the Shire itself – for while it may be a pleasant and even good place to visit or dwell, I think that its dullness to wonder and concern with the material and the known leaves it deficient in a strikingly modern fashion.

Tolkien once said that a safe fairy-land is untrue to all worlds, and ultimately this premise does hold true in the case of the Shire. For the Shire is indeed safe, and it is proud of its safety, though its safety is by no means wholly virtuous nor even something to be desired. In short, the Shire is safe from Faerie itself.

C. Williams who is reading it all says the great thing is that its centre is not in strife and war and heroism (though they are understood and depicted) but in freedom, peace, ordinary life and good liking. Yet he agrees that these very things require the existence of a great world outside the Shire – lest they should grow stale by custom and turn into the humdrum…

J.R.R. Tolkien, Letter 93 to Christopher Tolkien

~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Thanks for reading – feel free to check out anything else you may be interested in on the blog, there’s plenty more to discover! Follow me on Facebook and on Twitter to stay up to date with The Blog of Mazarbul, and if you want to join in the discussion, write a comment below or send an email. Finally, if you really enjoyed the post above, you can support the blog via Paypal, and keep The Blog of Mazarbul running. Thanks for reading, and may your beards never grow thin!

I came across this while researching a post about The Lord of the Rings as “deep fantasy” (and the Shire as its shallow end), and I think you hit the nail on the head; in fact, I shall probably quote this..

Please do feel free to quote from it – would love to see your own post when it’s published, too!