In my first post of this year’s September Series, I described Tolkien’s Shire as being a land of people in need of ‘faeriefication.’ The hobbits of the Shire are deliberately blinded to the delights of their Faerie world, and they themselves suffer a deficiency of otherworldly wonder and joy as a consequence of their small-mindedness.

This may all seem like rather an unkind take, and though I do stand by it, it is also well worth considering that the Shire is only an unFaerie realm on one level – the level of the Shire itself. For, while the Shire and its hobbit inhabitants may themselves treat Faerie with immutable distrust within their own lives, this is not to say that hobbits (nor, indeed, the Shire itself) are not Faerie beings.

On one level, this is self-evident, as they are sub-created denizens of a sub-created world. Yet nonetheless, it seems worthwhile to me to take that step back and, having been less than kind to hobbits in my previous post, to reconsider them from another, itself alien, perspective – a perspective which is wholly necessary not only for properly appreciating hobbits, but for appreciating them as other folk in Middle-earth must have.

For hobbits are not merely little rural English people from a half-remembered bygone era. For one, their feet are exceptionally tough and hairy and as a consequence they generally wear no shoes, and further are capable of moving very quietly at need. They live in holes dug into hills with round doors and comfortable warm interiors. They are a folk better-attuned to the They possess a strange doughtiness blended with humility that makes them perfectly suited to, say, bear world-conquering artefacts of unimaginable evil for at least a time.

And all of this is merely the ways in which the Shire and its inhabitants are alien and curious to us as readers, let alone to other inhabitants of Middle-earth. Consider, say, an Anglo-Saxon warrior stumbling upon a late 19th-century English parish, and you will have some idea of just how staggeringly strange the Shire is on its own terms – just how Faerie it is to the Rohirrim, Gondorians, Dwarves, and a dozen other cultures and peoples of Middle-earth. But I am getting ahead of myself.

Nonetheless, a recurrent concept within Tolkien’s fiction is that hobbits are strange indeed to many of the peoples of Middle-earth – and, given that the hobbits themselves are sheltered and unknowledgeable folk, this often results in fascinating moments of exchange. Some might consider them as being cultural exchange, but I am not an anthropologist and am ill-equipped to consider them from that light. But given the alien enchantment that can come across either one or both parties in such moments of encounter, I would like to consider them as being Faerie exchange…moments when an experience of Faerie is mutually experienced by both parties.

For an example of what I do not mean by this idea of mutually exchanged Faerie, consider Bilbo’s very first brush with the wider world and the strange, when he plays host to an unexpected Dwarvish dinner party. Throughout the course of the evening, Bilbo is infuriated by, wondering at, terrified of, and eagerly enchanted by Thorin’s words and history – in short, Bilbo (and the reader along with him) is faerie-touched.

Yet there is no such indication that Thorin, Gandalf, or any of the other Dwarves experience such stirrings due to Bilbo: indeed, it is rather the opposite. Thorin is irritated by Bilbo and doubtful of him, and not without good reason – both because Thorin has met Bilbo (even if he has not seen to his heart as surely as Gandalf) and because Thorin is familiar with the Shire to a degree. That familiarity does not just breed contempt, it breeds disenchantment – there is nothing arresting or strange or wondrously beautiful for Thorin or his companions to see in Bilbo, so they see him “for what he is.”

Indeed, The Hobbit rarely features any sort of faerie-wonder from characters toward Bilbo. In two key scenes, both Gollum and Smaug seem unfamiliar with Bilbo and his kind, and Smaug in particular is certainly fascinated – for a moment – by this invisible burglar. But the fascination turns all too soon to desire and wrath, and the fleeting fey spell is broken. Yet there is some evidence towards the end of The Hobbit of just how marvellous and curious Bilbo himself has become, when he sneaks the Arkenstone out of the Lonely Mountain and brings it to Thorin’s enemies, the Elvenking and Bard – and in the process, the Faerie formula of The Hobbit is unexpectedly reversed.

“That is how it came about that some two hours after his escape from the Gate, Bilbo was sitting beside a warm fire in front of a large tent, and there sat too, gazing curiously at him, both the Elvenking and Bard. A hobbit in elvish armour, partly wrapped in an old blanket, was something new to them.

“Really you know,” Bilbo was saying in his best business manner, “things are impossible. Personally I am tired of the whole affair. I wish I was back in the West in my own home, where folk are more reasonable. But I have an interest in this matter—one fourteenth share, to be precise, according to a letter, which fortunately I believe I have kept.”

…

“My dear Bard!” squeaked Bilbo. “Don’t be so hasty! I never met such suspicious folk! I am merely trying to avoid trouble for all concerned. Now I will make you an offer!”

“Let us hear it!” they said.

“You may see it!” said he. “It is this!” and he drew forth the Arkenstone, and threw away the wrapping.

The Elvenking himself, whose eyes were used to things of wonder and beauty, stood up in amazement. Even Bard gazed marvelling at it in silence. It was as if a globe had been filled with moonlight and hung before them in a net woven of the glint of frosty stars.

…

The Elvenking looked at Bilbo with a new wonder. “Bilbo Baggins!” he said. “You are more worthy to wear the armour of elf-princes than many that have looked more comely in it. But I wonder if Thorin Oakenshield will see it so. I have more knowledge of dwarves in general than you have perhaps. I advise you to remain with us, and here you shall be honoured and thrice welcome.”

The Hobbit, Chapter XVI, ‘A Thief in the Night,’ by J.R.R. Tolkien

Bilbo is, by this point, familiar with both Bard and the Elvenking. The former, though, was doubtless rather more struck with the returning Thorin than with his timid companion during their stay in Lake-town, and the latter has never met him properly at all, on account of Bilbo’s having invisibly enjoyed his unknowing hospitality for some weeks.

Hence, Bilbo is in his element, conducting a deal he has conceived and orchestrated, with folk with whom he is passingly familiar – there is nothing to suggest any great Faerie wonder from Mr Baggins in at least this point in the story. But both Bard and the Elvenking are meeting an unfamiliar creature, who bears strange news and a marvellous artefact (and has shown no small amount of bravery, cunning and skill in sneaking so close to their camp and past their elvish guards) – in this moment, at least, we see them in the grips of Faerie wonder, while Bilbo is on surprisingly sure ground.

All of this is to say that while The Hobbit features relatively sparse examples of mutual Faeriefication, it does not forget to relish in just how strange Bilbo is – in appearance and in deed – to at least some of those that he encounters on his travels.

But if we want to consider Faerie exchange, we must turn to The Lord of the Rings and to the hobbits of the Fellowship – particularly as they press forth in ever more southerly and distant lands.

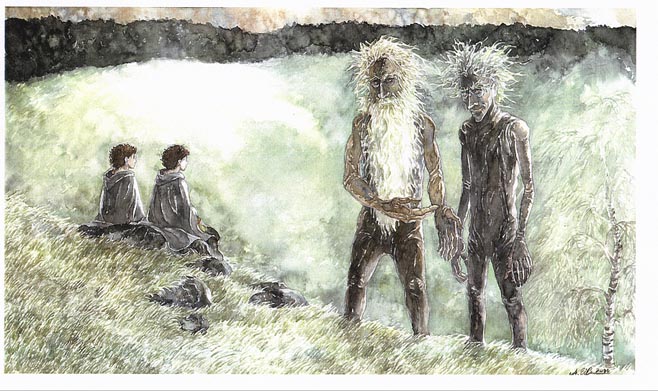

Indeed, the example which inspired this entire post is perhaps the most memorable of the piece – the encounter of Merry and Pippin with Treebeard. For us the readers, it is clear from the first that Treebeard is an extraordinary and strange being, and we are invited to experience him as such through Merry and Pippin’s eyes.

They found that they were looking at a most extraordinary face. It belonged to a large Man-like, almost Troll-like, figure, at least fourteen foot high, very sturdy, with a tall head, and hardly any neck. Whether it was clad in stuff like green and grey bark, or whether that was its hide, was difficult to say. At any rate the arms, at a short distance from the trunk, were not wrinkled, but covered with a brown smooth skin. The large feet had seven toes each. The lower part of the long face was covered with a sweeping grey beard, bushy, almost twiggy at the roots, thin and mossy at the ends. But at the moment the hobbits noted little but the eyes. These deep eyes were now surveying them, slow and solemn, but very penetrating. They were brown, shot with a green light. Often afterwards Pippin tried to describe his first impression of them.

‘One felt as if there was an enormous well behind them, filled up with ages of memory and long, slow, steady thinking; but their surface was sparkling with the present; like sun shimmering on the outer leaves of a vast tree, or on the ripples of a very deep lake. I don’t know, but it felt as if something that grew in the ground – asleep, you might say, or just feeling itself as something between root-tip and leaf-tip, between deep earth and sky had suddenly waked up, and was considering you with the same slow care that it had given to its own inside affairs for endless years.’

The Lord of the Rings, Book III, Chapter 3, ‘Treebeard,’ by J.R.R. Tolkien

But within a few lines, something curious becomes apparent – that Treebeard is himself just as enchanted by Merry and Pippin, and that he has just as little idea what to make of them (and is just as eager to learn more about them) as they are him.

‘Hrum, Hoom ,’ murmured the voice, a deep voice like a very deep woodwind instrument. ‘Very odd indeed! Do not be hasty, that is my motto. But if I had seen you, before I heard your voices – I liked them: nice little voices; they reminded me of something I cannot remember – if I had seen you before I heard you, I should have just trodden on you, taking you for little Orcs, and found out my mistake afterwards. Very odd you are, indeed. Root and twig, very odd!’

…

‘Hoo now!’ replied Treebeard. ‘Hoo! Now that would be telling! Not so hasty. And I am doing the asking. You are in my country. What are you , I wonder? I cannot place you. You do not seem to come in the old lists that I learned when I was young. But that was a long, long time ago, and they may have made new lists. Let me see! Let me see! How did it go?

Learn now the lore of Living Creatures!

First name the four, the free peoples:

Eldest of all, the elf-children;

Dwarf the delver, dark are his houses;

Ent the earthborn, old as mountains;

Man the mortal, master of horses:

Hm, hm, hm.

Beaver the builder, buck the leaper,

Bear bee-hunter, boar the fighter;

Hound is hungry, hare is fearful . . .

hm, hm.

Eagle in eyrie, ox in pasture,

Hart horn-crownéd;

hawk is swiftest,

Swan the whitest, serpent coldest . . .

Hoom, hm; hoom, hm, how did it go? Room tum, room tum, roomty toom tum. It was a long list. But anyway you do not seem to fit in anywhere!’

LOTR, ‘Treebeard’

In short, this is a clear example of not just unfamiliarity on both parts (as was the case, say, with Bilbo and Smaug) but of actual wonder and amazement. For Merry and Pippin, they have wandered into a Faerie place – but equally for Treebeard, Faerie beings have intruded upon his home. And it is clear, as the friendship between this oldest and slowest of Ents and these merry and youthful hobbits develops, that on both sides there is a wonderful enchantment and enrichment that takes place – that Treebeard gains quite as much from the chance encounter as Merry and Pippin, really. By the time of their final parting, there is a deep and mutual admiration and love, and it is a love founded in differences as much as it is in a common cause.

And, while it is with Treebeard (and later Quickbeam) that the hobbits find a special friendship with, there is nonetheless a marvel and a mutual curiosity expressed between hobbits and Ents when the Entmoot is assembled, and the hobbits find themselves wondering at the great variety and the peculiar similarities between the various Ents – and in turn, the tree-shepherds are delighted by the (to them incredible) midriff flexibility enjoyed by less treeish creatures.

At first Merry and Pippin were struck chiefly by the variety that they saw: the many shapes, and colours, the differences in girth, and height, and length of leg and arm; and in the number of toes and fingers (anything from three to nine). A few seemed more or less related to Treebeard, and reminded them of beech-trees or oaks. But there were other kinds. Some recalled the chestnut: brown-skinned Ents with large splayfingered hands, and short thick legs. Some recalled the ash: tall straight grey Ents with many-fingered hands and long legs; some the fir (the tallest Ents), and others the birch, the rowan, and the linden. But when the Ents all gathered round Treebeard, bowing their heads slightly, murmuring in their slow musical voices, and looking long and intently at the strangers, then the hobbits saw that they were all of the same kindred, and all had the same eyes: not all so old or so deep as Treebeard’s, but all with the same slow, steady, thoughtful expression, and the same green flicker .

…

[Treebeard] put the hobbits down. Before they walked away, they bowed low. This feat seemed to amuse the Ents very much, to judge by the tone of their murmurs, and the flicker of their eyes; but they soon turned back to their own business.

LOTR, ‘Treebeard’

So far, so good. Yet this Faerie enrichment is further complicated and informed by the entry of Théoden and the Rohirrim into the picture. Théoden wonders at Ents and Hobbits alike, but his wonder is distinct to the wonder of Treebeard and the duo. For, to Théoden, he is not meeting entirely unfamiliar creatures, as such, as both Ents and Hobbits are tinged with a certain familiarity.

Gandalf laughed long and merrily. ‘The trees?’ he said. ‘Nay, I see the wood as plainly as do you. But that is no deed of mine. It is a thing beyond the counsel of the wise. Better than my design, and better even than my hope the event has proved.’

‘Then if not yours, whose is the wizardry?’ said Théoden. ‘Not Saruman’s, that is plain. Is there some mightier sage, of whom we have yet to learn?’

‘It is not wizardry, but a power far older,’ said Gandalf: ‘a power that walked the earth, ere elf sang or hammer rang.

Ere iron was found or tree was hewn,

When young was mountain under moon;

Ere ring was made, or wrought was woe,

It walked the forests long ago.’

‘And what may be the answer to your riddle?’ said Théoden.

‘If you would learn that, you should come with me to Isengard,’ answered Gandalf.

LOTR, Book III, Chapter 8, ‘The Road to Isengard’

And as it transpires, Théoden is perfectly aware of what an Ent ‘is,’ for they are legends and mythical figures on the edge of fanciful tales in his land. In other words, the Ents are not just Faerie to Théoden, they are also quite literally fairy-tales.

Even as [Gandalf] spoke, there came forward out of the trees three strange shapes. As tall as trolls they were, twelve feet or more in height; their strong bodies, stout as young trees, seemed to be clad with raiment or with hide of close-fitting grey and brown. Their limbs were long, and their hands had many fingers; their hair was stiff, and their beards grey-green as moss. They gazed out with solemn eyes, but they were not looking at the riders: their eyes were bent northwards. Suddenly they lifted their long hands to their mouths, and sent forth ringing calls, clear as notes of a horn, but more musical and various. The calls were answered; and turning again, the riders saw other creatures of the same kind approaching, striding through the grass. They came swiftly from the North, walking like wading herons in their gait, but not in their speed; for their legs in their long paces beat quicker than the heron’s wings. The riders cried aloud in wonder, and some set their hands upon their sword-hilts.

‘You need no weapons,’ said Gandalf. ‘These are but herdsmen. They are not enemies, indeed they are not concerned with us at all.’

So it seemed to be; for as he spoke the tall creatures, without a glance at the riders, strode into the wood and vanished.

‘Herdsmen!’ said Théoden. ‘Where are their flocks? What are they, Gandalf? For it is plain that to you, at any rate, they are not strange.’

‘They are the shepherds of the trees,’ answered Gandalf. ‘Is it so long since you listened to tales by the fireside? There are children in your land who, out of the twisted threads of story, could pick the answer to your question. You have seen Ents, O King, Ents out of Fangorn Forest, which in your tongue you call the Entwood. Did you think that the name was given only in idle fancy? Nay, Théoden, it is otherwise: to them you are but the passing tale; all the years from Eorl the Young to Théoden the Old are of little count to them; and all the deeds of your house but a small matter.’

The king was silent. ‘Ents!’ he said at length. ‘Out of the shadows of legend I begin a little to understand the marvel of the trees, I think. I have lived to see strange days. Long we have tended our beasts and our fields, built our houses, wrought our tools, or ridden away to help in the wars of Minas Tirith. And that we called the life of Men, the way of the world. We cared little for what lay beyond the borders of our land. Songs we have that tell of these things, but we are forgetting them, teaching them only to children, as a careless custom. And now the songs have come down among us out of strange places, and walk visible under the Sun.’

LOTR, ‘The Road to Isengard’

This motif of the Rohirrim encountering creatures of myth and fairytale is then quickly reinforced a little later, when Théoden’s company comes to the gates of Isengard and is met by yet another strange and marvellous sight.

And now they turned their eyes towards the archway and the ruined gates. There they saw close beside them a great rubble-heap; and suddenly they were aware of two small figures lying on it at their ease, grey- clad, hardly to be seen among the stones. There were bottles and bowls and platters laid beside them, as if they had just eaten well, and now rested from their labour. One seemed asleep; the other, with crossed legs and arms behind his head, leaned back against a broken rock and sent from his mouth long wisps and little rings of thin blue smoke.

For a moment Théoden and Éomer and all his men stared at them in wonder. Amid all the wreck of Isengard this seemed to them the strangest sight. But before the king could speak, the small smoke-breathing figure became suddenly aware of them, as they sat there silent on the edge of the mist. He sprang to his feet. A young man he looked, or like one, though not much more than half a man in height; his head of brown curling hair was uncovered, but he was clad in a travel-stained cloak of the same hue and shape as the companions of Gandalf had worn when they rode to Edoras. He bowed very low, putting his hand upon his breast. Then, seeming not to observe the wizard and his friends, he turned to Éomer and the king.

…

The Riders laughed. ‘It cannot be doubted that we witness the meeting of dear friends,’ said Théoden. ‘So these are the lost ones of your company, Gandalf? The days are fated to be filled with marvels. Already I have seen many since I left my house; and now here before my eyes stand yet another of the folk of legend. Are not these the Halflings, that some among us call the Holbytlan?’

‘Hobbits, if you please, lord,’ said Pippin.

‘Hobbits?’ said Théoden. ‘Your tongue is strangely changed; but the name sounds not unfitting so. Hobbits! No report that I have heard does justice to the truth.’

Merry bowed; and Pippin got up and bowed low. ‘You are gracious, lord; or I hope that I may so take your words,’ he said. ‘And here is another marvel! I have wandered in many lands, since I left my home, and never till now have I found people that knew any story concerning hobbits. ’

‘My people came out of the North long ago,’ said Théoden. ‘But I will not deceive you: we know no tales about hobbits. All that is said among us is that far away, over many hills and rivers, live the halfling folk that dwell in holes in sand-dunes. But there are no legends of their deeds, for it is said that they do little, and avoid the sight of men, being able to vanish in a twinkling; and they can change their voices to resemble the piping of birds. But it seems that more could be said.’

‘It could indeed, lord,’ said Merry.

‘For one thing,’ said Théoden, ‘I had not heard that they spouted smoke from their mouths.’

LOTR, ‘The Road to Isengard’

This, too, marks some shift in the familiarity – for we see that the hobbits are not wholly unfamiliar to the Rohirrim (if only by way of somewhat exaggerated rumour) and that, in turn, is of great surprise to Merry and Pippin. Likewise, Merry and Pippin easily discover common ground with Théoden, though their meeting with him yet remains wondrous (particularly for Merry’s part, who ends up being rather Faerie-touched by his extended sojourn in the company of the Rohirrim, and Théoden especially). Hence, we can see that mutual enFaerification at work on hobbits and Rohirrim alike. Further, their shared cultural origins quickly provide hobbits and Rohirrim alike with plenty of fertile ground in which to share a mutual kinship, as opposed to the hobbits (or even the Rohirrim) with the wholly alien Ents.

Speaking of which, this Faerie wonder is not mutual on the part of the Ents, who seem thoroughly unstirred by the Rohirrim. For them, the Rohirrim are indeed ‘common,’ earthly beings, their ways known and their desires understood. Treebeard demonstrates clear familiarity with the Rohirrim, and arguably knows them better than they know themselves, for he knew the land ere it was Rohan and ere any Rider came from the north.

In short, we see a fascinating example of a triangular mutual Faerie experience in the meetings of hobbits, Ents, and Rohirrim. To the Rohirrim, the Ents are a legend, but to the Ents, the Riders are but merely the latest tenants of the plains. To Merry and Pippin, the Rohirrim are strange Men yet familiar in their cultural background – and likewise, the Rohirrim are familiar with tales concerning Hobbits yet still find much to marvel at. And finally, Hobbits and Ents alike are astounded at the other, having virtually no common ground and virtually no information (even mythicised) concerning the other, and so both share in a joy and a delight at coming to know the other.

‘Yes, we must go, and go now,’ said Gandalf. ‘I fear that I must take your gatekeepers from you. But you will manage well enough without them.’

‘Maybe I shall,’ said Treebeard. ‘But I shall miss them. We have become friends in so short a while that I think I must be getting hasty – growing backwards towards youth, perhaps. But there, they are the first new thing under Sun or Moon that I have seen for many a long, long day. I shall not forget them. I have put their names into the Long List. Ents will remember it.

Ents the earthborn, old as mountains,

the wide-walkers, water drinking;

and hungry as hunters, the Hobbit children,

the laughing-folk, the little people,

they shall remain friends as long as leaves are renewed. Fare you well! But if you hear news up in your pleasant land, in the Shire, send me word! You know what I mean: word or sight of the Entwives. Come yourselves if you can!’

‘We will!’ said Merry and Pippin together, and they turned away hastily. Treebeard looked at them, and was silent for a while, shaking his head thoughtfully.

LOTR, Book VI, Chapter 6, ‘Many Partings’

Ent, Rider and Hobbit – all mutually enriched in Faerie by having experienced the other. Merry comes to better understand kindly valour and noble heroism through the example of his King, and Théoden in his elder days is touched by the simple cheer and mighty spirit of his fairy-esquire. Further, Théoden beholds some remnant of the Elder Days and a matter of song and legend among his people and the children of his people, while Treebeard enjoys the company of folk genuinely new to him and (I like to think) finds some fresh wisdom in them; while Merry and Pippin are raised in stature by Treebeard – in many more ways than one (though the literal lends itself to the figurative).

This post is already running overlong, but it is worth touching (if briefly) upon other moments of mutual enFaerification through The Lord of the Rings. Frodo and Sam experience it in Ithilien when they meet Faramir – who in turn is changed through his having come to know them. The entire story of Legolas and Gimli can be viewed as being a Faerie journey for each of them, as externalised by Legolas’ love for Fangorn and the extraordinary eloquence of Gimli in describing the Glittering Caves (an eloquence Legolas later admits is not only deserved, but that he cannot himself match).

Pippin’s time in Minas Tirith, too, is illustrative of mutually granted Faerie experience, as chiefly demonstrated through his friendship with Beregond. And it is worth tarrying for a moment on that Gondor’s relationship with the halflings of the North is distinct from that of Rohan – for in Rohan, the little people seem to form some part of their actual cultural heritage. And, while the word ‘halfling’ is clearly not unknown in Gondor, as of the time of the War of the Ring, it has itself been granted some fresh Faerie significance.

Seek for the Sword that was broken:

In Imladris it dwells;

There shall be counsels taken

Stronger than Morgul-spells.

There shall be shown a token

That Doom is near at hand,

For Isildur’s Bane shall waken,

And the Halfling forth shall stand.

LOTR, Book II, Chapter 2, ‘The Council of Elrond’

This prophetic dream of Faramir and Boromir means that ‘halfling’ is a word fresh-laden with significance and omen by the time Gandalf brings Pippin to Minas Tirith and, while the young hobbit himself is clearly struck by the ancient glories of the White City, he himself is no less a wonder to the folk there.

Presently he noticed a man, clad in black and white, coming along the narrow street from the centre of the citadel towards him. Pippin felt lonely and made up his mind to speak as the man passed; but he had no need. The man came straight up to him.

‘You are Peregrin the Halfling?’ he said. ‘I am told that you have been sworn to the service of the Lord and of the City. Welcome!’ He held out his hand and Pippin took it.

‘I am named Beregond son of Baranor. I have no duty this morning, and I have been sent to you to teach you the pass-words, and to tell you some of the many things that no doubt you will wish to know. And for my part, I would learn of you also. For never before have we seen a halfling in this land and though we have heard rumour of them, little is said of them in any tale that we know.’

…

Gandalf was not in the lodging and had sent no message; so Pippin went with Beregond and was made known to the men of the Third Company. And it seemed that Beregond got as much honour from it as his guest, for Pippin was very welcome. There had already been much talk in the citadel about Mithrandir’s companion and his long closeting with the Lord; and rumour declared that a Prince of the Halflings had come out of the North to offer allegiance to Gondor and five thousand swords. And some said that when the Riders came from Rohan each would bring behind him a halfling warrior, small maybe, but doughty.

Though Pippin had regretfully to destroy this hopeful tale, he could not be rid of his new rank, only fitting, men thought, to one befriended by Boromir and honoured by the Lord Denethor; and they thanked him for coming among them, and hung on his words and stories of the outlands, and gave him as much food and ale as he could wish.

…

He went out, and soon after all the others followed. The day was still fine, though it was growing hazy, and it was hot for March, even so far southwards. Pippin felt sleepy, but the lodging seemed cheerless, and he decided to go down and explore the City….

People stared much as he passed. To his face men were gravely courteous, saluting him after the manner of Gondor with bowed head and hands upon the breast; but behind him he heard many calls, as those out of doors cried to others within to come and see the Prince of the Halflings, the companion of Mithrandir. Many used some other tongue than the Common Speech, but it was not long before he learned at least what was meant by Ernil i Pheriannath and knew that his title had gone down before him into the City.

LOTR, Book V, Chapter 1, ‘Minas Tirith’

Further, though, this Gondorian Faerie-curiosity for Peregrin, Prince of the Halflings is not universal. For there is at least one character in Gondor who, though he has many questions for Pippin, shows no actual interest in Pippin himself or in what he ‘is’ – and that lack of Faerie interest is, I think, key to understanding the thought and mode of Denethor.

In Letter 183, Tolkien describes Denethor as having been ‘tainted with mere politics,’ and that this taint leads both to Denethor’s failure and to his misapprehension concerning the entire War of the Ring. Denethor, Tolkien says, saw the battle against Sauron not as being a war of Good and Evil, but as being a mere struggle between political figures over power and territory – Sauron was not to be opposed owing to any specific wickednesses he might or would condone, but because he threatened the sovereignty of Gondor (and thus Denethor’s own power).

What is interesting is that this lack of concern on Denethor’s part with such trifles beyond territory and empire is strikingly apparent from his introduction in the story, when he meets Pippin. For, while Denethor is deeply interested in what Pippin has to tell him, he is not at all interested in what Pippin is – near-alone of all the Men of Gondor, Denethor shows a complete disregard for the hobbit from a Faerie land that has entered into his own grey walls.

Then the old man looked up. Pippin saw his carven face with its proud bones and skin like ivory, and the long curved nose between the dark deep eyes; and he was reminded not so much of Boromir as of Aragorn. ‘Dark indeed is the hour,’ said the old man, ‘and at such times you are wont to come, Mithrandir. But though all the signs forebode that the doom of Gondor is drawing nigh, less now to me is that darkness than my own darkness. It has been told to me that you bring with you one who saw my son die. Is this he?’

‘It is,’ said Gandalf. ‘One of the twain. The other is with Théoden of Rohan and may come hereafter. Halflings they are, as you see, yet this is not he of whom the omens spoke.’

‘Yet a Halfling still,’ said Denethor grimly, ‘and little love do I bear the name, since those accursed words came to trouble our counsels and drew away my son on the wild errand to his death. My Boromir! Now we have need of you. Faramir should have gone in his stead.’

‘He would have gone,’ said Gandalf. ‘Be not unjust in your grief! Boromir claimed the errand and would not suffer any other to have it. He was a masterful man, and one to take what he desired. I journeyed far with him and learned much of his mood. But you speak of his death. You have had news of that ere we came?’

‘I have received this,’ said Denethor, and laying down his rod he lifted from his lap the thing that he had been gazing at. In each hand he held up one half of a great horn cloven through the middle: a wild-ox horn bound with silver.

‘That is the horn that Boromir always wore!’ cried Pippin.

‘Verily,’ said Denethor. ‘And in my turn I bore it, and so did each eldest son of our house, far back into the vanished years before the failing of the kings, since Vorondil father of Mardil hunted the wild kine of Araw in the far fields of Rhûn. I heard it blowing dim upon the northern marches thirteen days ago, and the River brought it to me, broken: it will wind no more.’ He paused and there was a heavy silence. Suddenly he turned his black glance upon Pippin. ‘What say you to that, Halfling?’

LOTR, ‘Minas Tirith’

Denethor expresses curiosity in Pippin not for what he is or where he is from, but in what he knows (especially as it relates to Denethor’s own interests: defending against Mordor, learning more of Boromir’s fate, and protecting the Stewardship from any ragged Rangers who might come a-knocking). Denethor treats with Pippin no differently than it seems he treats with any traveller or guest; which is drawn in sharp contrast with the people of Minas Tirith. In Minas Tirith, a love for the strange and unknown remains, as demonstrated in large (the instant celebrity Pippin accidentally achieves) and in individual vignettes (Beregond, Bergil, Ioreth and even the Steward of the Houses of Healing all express wonder and curiosity in talking with or about Hobbits).

This disdain for Faerie in Denethor is deliberate, I think, in that it reveals a broader truth about his character. Denethor does not see Elves and Hobbits and marvels. He sees obstacles to power, and mechanisms by which to overcome those obstacles. Pippin and the palantír are two such mechanisms; explicitly and clearly Faerie marvels that Denethor perceives as being tools. Sauron and Gandalf, on the other hand, are obstacles. One a military threat and the other a diplomatic concern, yet obstacles nonetheless – in spite of their lofty histories.

In this sense, Denethor is himself surprisingly hobbit-like. As discussed in the previous post, there is an almost offensive incuriosity about most Hobbits, and it is this incuriosity that enables Saruman to take advantage of them. Denethor is certainly more worldly and wise than likely any hobbit, yet he suffers from the same blindnesses that they possess, being unable to see beyond his own concerns and doings. Denethor is just as blind to Faerie as any Bolger or Bracegirdle…though I do not know whether the lofty Steward or those homely Hobbits would resent the comparison more.

There are numerous other such examples of mutual Faerie experience across Tolkien’s works; examples of two people or peoples coming together and finding a shared wonder in the strangeness and familiarity of the other. Give that this series is focused specifically upon the theme of Faerie specifically as it relates to hobbits, I will not dwell overlong on examples of this mutual faerie wonder in other of Tolkien’s works (and will return to one final hobbit-based example to close this post). But there is one example in particular that is worth observing, if only in brief. Athrabeth Finrod ah Andreth.

“The Debate of Finrod and Andreth” may be drily titled, but it is one of Tolkien’s most moving, rich and intriguingly empathetic works, as an Elvish lord and a Mannish wisewoman consider issues of love, death, doubt, and hope; rooted in the perspectives and limited knowledge of each character in turn. It is a wide-ranging and deeply philosophical text, but is permeated throughout with a sense of curiosity and wonder (and on occasion, even jealousy) on the parts of both Finrod and Andreth in turn.

It is, in short, truly the perfect example of this mutual Faerie encounter, and is well worth highlighting – not in the least for the sake of clarifying that this mutual enFaerying is not necessarily a thing of joy for both or for either party. Though it is almost always a thing of deep worth.

Did I say the perfect? For perhaps I spoke too soon – for there is one, final example of mutual Faerie experience in The Lord of the Rings that I would like to highlight and that, fittingly, serves as the culmination and the triumph of the entire Quest and the War of the Ring, as Frodo and Sam are honoured by the Host of the West on the Field of Cormallen.

As they came to the opening in the wood, they were surprised to see knights in bright mail and tall guards in silver and black standing there, who greeted them with honour and bowed before them. And then one blew a long trumpet, and they went on through the aisle of trees beside the singing stream. So they came to a wide green land, and beyond it was a broad river in a silver haze, out of which rose a long wooded isle, and many ships lay by its shores. But on the field where they now stood a great host was drawn up, in ranks and companies glittering in the sun. And as the Hobbits approached swords were unsheathed, and spears were shaken, and horns and trumpets sang, and men cried with many voices and in many tongues:

‘Long live the Halflings! Praise them with great praise!

Cuio i Pheriain anann! Aglar’ni Pheriannath!

Praise them with great praise, Frodo and Samwise!

Daur a Berhael, Conin en Annûn! Eglerio!

Praise them!

Eglerio!

A laita te, laita te! Andave laituvalmet!

Praise them!

Cormacolindor, a laita tárienna!

Praise them! The Ring-bearers, praise them with great praise!’

…

And when the glad shout had swelled up and died away again, to Sam’s final and complete satisfaction and pure joy, a minstrel of Gondor stood forth, and knelt, and begged leave to sing. And behold! he said:

‘Lo! lords and knights and men of valour unashamed, kings and princes, and fair people of Gondor, and Riders of Rohan, and ye sons of Elrond, and Dúnedain of the North, and Elf and Dwarf, and greathearts of the Shire, and all free folk of the West, now listen to my lay. For I will sing to you of Frodo of the Nine Fingers and the Ring of Doom.’

And when Sam heard that he laughed aloud for sheer delight, and he stood up and cried: ‘O great glory and splendour! And all my wishes have come true!’ And then he wept.

And all the host laughed and wept, and in the midst of their merriment and tears the clear voice of the minstrel rose like silver and gold, and all men were hushed. And he sang to them, now in the elven-tongue, now in the speech of the West, until their hearts, wounded with sweet words, overflowed, and their joy was like swords, and they passed in thought out to regions where pain and delight flow together and tears are the very wine of blessedness.

LOTR, Book VI, Chapter 4, ‘The Field of Cormallen’

Here, on the one hand we have the folk of Rohan and Gondor and the North, all arrayed to behold the miraculous deliverers of their succour; these two small and ragged and humble hobbits – and on the other, Frodo and Sam, their dreadful and long journey now finally at an end, are granted honour and recognition beyond anything they might ever have imagined by lordly captains and warriors and heroes. All are moved to tears and joy, and all are filled with wonder at the other.

And the minstrel, of course, sings – thus forming Frodo and the Ring of Doom as surely as possible into a Faerie tale, a story of Faerie to be shared and wondered at by Frodo and Sam and the Host alike and to the fierce joy of them all.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Thanks for reading – feel free to check out anything else you may be interested in on the blog, there’s plenty more to discover! Follow me on Facebook and on Twitter to stay up to date with The Blog of Mazarbul, and if you want to join in the discussion, write a comment below or send an email. Finally, if you really enjoyed the post above, you can support the blog via Paypal, and keep The Blog of Mazarbul running. Thanks for reading, and may your beards never grow thin!