Recovery, Escape, Consolation

These three functions are presented by Tolkien in On Fairy Stories as being the noble and proper graces that Faerie and fairy-tale provides; the functions that both serve in their proper form. Fairy stories, Tolkien says, lend a metaphysical comfort and keen succour to the reader who willingly enters into their sub-created enchantment. This is, in a way, a theological function of Faerie – to provide the reader with some fleeting (though not untrue) measure of spiritual bliss.

It is perhaps no surprise that the ideas of Recovery and Consolation have often been considered in light of the ending of The Lord of the Rings, in which Frodo and Bilbo pass over the Sea to Elvenhome – to live out their days in a literal and earthly Faerie paradise. For Frodo and Bilbo have suffered great pains through their bearing of the One Ring, and the consolation afforded to them in Valinor is healing and restorative. And naturally, Sam’s own purported journey to Valinor later in his life lends much credence to such discussions, for Sam too bore the Ring, and was troubled by it in how it blighted Frodo.

As such, I am rather less interested in this, the final post of the 2024 September Series, in considering Recovery or Consolation as they relate to this Faerie-tinged ending. Rather, I would like to consider Escape…and a faeriean Escape as it relates not just to Frodo, Bilbo, and Sam, but also to Merry and Pippin, who do not go to Valinor at all! But as ever, I am getting ahead of myself – it is worthwhile first, perhaps, to readdress what ‘Faerie’ even means.

Through this series, we have spent a lot of time rather deliberately avoiding any sort of definition or declaration concerning what exactly Faerie is. But for the sake of this article, let us consider Faerie as being the unfamiliar, the wondrous, and the terrifying. It is a state of enchantment and a condition which must be accepted if it is to be effective.

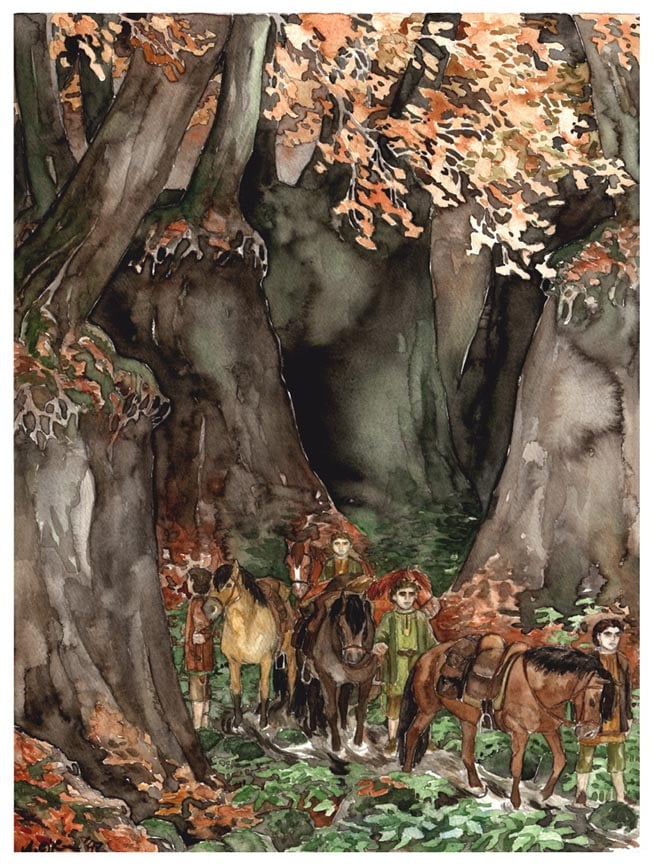

As readers of Tolkien, we are treated to a Faerie within Faerie, as it were. For not only do we experience the Faerie of Middle-earth, we are also privileged to enjoy that Faerie through the eyes of Tolkien’s hobbit protagonists – through the eyes of Bilbo, Frodo, Sam, Merry, and Pippin. These characters are themselves wanderers on a Faerie journey; ordinary and small folk thrust into a mysterious and great world.

This preamble is all in aid of establishing one extremely pertinent fact – that, for Tolkien’s five hobbit heroes, the Shire is not Faerie (though it may be for the reader, and as previously discussed, also for others of Middle-earth’s inhabitants). The Shire is familiar, comfortable, and home. The rest of the world, even places as close as the Old Forest and Bree, are assuredly Faerie realms, but the Shire is not.

Memorably, this is alluded to as the remainder of the Fellowship finds themselves on the road back to Buckland and the Shire, at the end of all their adventures.

‘Well here we are, just the four of us that started out together,’ said Merry. ‘We have left all the rest behind, one after another. It seems almost like a dream that has slowly faded.’

‘Not to me,’ said Frodo. ‘To me it feels more like falling asleep again.’

The Lord of the Rings, Book VI, Chapter 7 ‘Homeward Bound,’ by J.R.R. Tolkien

It is an enigmatic and discomfiting moment, and that informs much of this post – suffice it to say for the moment that in at least one aspect, Merry and Frodo are here in accord. While their feelings may be other, the cause is the same – they are slipping out of Faerie and back into their own world. Both of them (and Sam and Pippin) have been marked by Faerie.

Some years later, Frodo and Bilbo take the ship at the Grey Havens and pass into the Uttermost West, where they eventually die. Sam, Merry and Pippin settle into Shire life and are marked with high regard; and each accomplishes much according to their ‘station.’ They marry, they have children, they govern and write and travel. And then, many years later, Sam too makes the journey to the Undying Lands, and the last of the Ringbearers dies there too.

Merry and Pippin were not ringbearers, though, and so this grace is not afforded to them – nor is there any indication that they especially need it (certainly not as much as Bilbo, Frodo and Sam did). Yet it is Merry and Pippin who inspired the initial concept of this article, for while they do not go to Valinor, there is nonetheless a striking similarity between them and their friends that I’ve never seen investigated. For Merry and Pippin, a couple of years after Sam’s departure, make one final great journey back to Rohan first, meeting with King Éomer before his death and then travelling on to Gondor, where they die and are laid to rest in the tombs of Rath Dínen…and in time, King Aragorn Elessar himself dies and the resting places of Merry and Pippin are set beside him.

It is a beautiful and moving conclusion to the story of each of the hobbits, but there is a curious element that ties the fate of the Ringbearers and companions alike together. For none of these hobbits die in the Shire. Every single one of them passes away and is laid to rest in Faerie. Every single of those five hobbits ‘escapes’ the Shire, ultimately, in favour of tarrying in a Faerie land. Not one of them dies in the Shire itself.

For Minas Tirith, remember, is a Faerie realm, if less mystically so than Valinor is. It can be hard to remember that, given how much history Tolkien laid out about Gondor and how familiar many readers have become with it! Yet it is assuredly a Faerie-realm, both on a narrative level and to the Shire-folk themselves within the story. And it is the Faerie-realm that is ‘fitting’ in a way for Merry and Pippin, who were not Ring-bearers, and did not venture into Mordor or suffer as Frodo and Sam suffered.

Or to put it another way, the lofty suffering and joy of Frodo and Sam is thus one best matched by coming to the Undying Lands…while for the rather more worldly and practical Merry and Pippin, their returning to Gondor is a mete Faerie adventure for them. For in both cases, the ‘Escape’ matches their prior experience.

This is significant, I think. Much has been written and considered concerning the departure of Bilbo, Frodo and (eventually) Sam from the Shire to pass away in the Uttermost West. Yet much of this material considers their passing on their terms as Ringbearers; mortals who have suffered a glimpse of a high and ancient and terrible power and who now must be healed of that pain. In short, much of it is concerned with the Recovery and Consolation of the Ringbearers themselves.

Yet Escape, too, is a distinctly Faerie quality. And though the Shire may be a fine and wonderful home in which to dwell, there is something compelling and almost addictive about the promise of a Faerie escape. Indeed, across Tolkien’s writings, it is impossible to deny his awareness that among the varied and distinctive powers of Faerie is its addictive and compelling nature. And Tolkien was also aware that Merry and Pippin did not escape unscathed (say rather unchanged) from their adventures in the Perilous Realm.

Frodo is not intended to be another Bilbo… But he is rather a study of a hobbit broken by a burden of fear and horror — broken down, and in the end made into something quite different. None of the hobbits come out of it in pure Shire-fashion. They wouldn’t.

Tolkien, Letter 151 to Hugh Brogan

If we read the Shire as ‘home’ to the hobbit protagonists, and the world as being ‘Faerie,’ is it not inevitable that they should inevitably seek to depart it, having previously tasted of the joys of Faerie? Indeed, this entire concept is presaged from the very beginning of LOTR, which begins as it ends – with Bilbo leaving home.

‘Yes, I am. I feel I need a holiday, a very long holiday, as I have told you before. Probably a permanent holiday: I don’t expect I shall return. In fact, I don’t mean to, and I have made all arrangements.

‘I am old, Gandalf. I don’t look it, but I am beginning to feel it in my heart of hearts. Well-preserved indeed!’ he snorted. ‘Why, I feel all thin, sort of stretched , if you know what I mean: like butter that has been scraped over too much bread. That can’t be right. I need a change, or something.’

Gandalf looked curiously and closely at him. ‘No, it does not seem right,’ he said thoughtfully. ‘No, after all I believe your plan is probably the best.’

‘Well, I’ve made up my mind, anyway. I want to see mountains again, Gandalf – mountains; and then find somewhere where I can rest. In peace and quiet, without a lot of relatives prying around, and a string of confounded visitors hanging on the bell. I might find somewhere where I can finish my book. I have thought of a nice ending for it: and he lived happily ever after to the end of his days.’

LOTR, Book I, Chapter 1, ‘A Long-Expected Party,’ by J.R.R. Tolkien

What is especially striking about this departure of Bilbo isn’t the weight of the Ring that he is unknowingly experiencing (for the Ring certainly would not be driving Bilbo to travel to Rivendell!); it is the fact that Bilbo is already living ‘happily ever after to the end of his days.’ There is no danger, no pressing errand that Bilbo is being forced into. Indeed, this issue of Bilbo living ‘happily ever after’ was present on Tolkien’s mind while he wrote LOTR, given that he had said just that in The Hobbit! And though Bilbo does indeed live very happily, there is nonetheless this dissatisfaction, this craving and desire and deep-rooted urge within him to see more mountains and fewer visitors.

Bilbo wishes, in short, to escape back to Faerie – and he does so. Twice over, given that he spends the next couple of decades in Rivendell before passing over the Sea. But this Escape that Bilbo craves has rather less to do with the Ring, and everything to do with Bilbo’s eyes having been opened through his previous adventure, and through his long and eager years of study and learning since then.

Bilbo has been Faerie-struck – as are Frodo and Sam, and Merry and Pippin. They do not leave the Shire at the end of their lives due to any great fault of the Shire, but because they have been awoken to Faerie’s joys and, as long as they live and are able to return to those joys, they will do so.

And there is a further piece of evidence for this reading of LOTR’s text, but it is not to be found in those esteemed books, or even in Tolkien’s wider writings. No, for further evidence of Faerie’s bewitching and compelling quality, we must journey with Tolkien’s great wanderer in Faery – with Smith, the far-traveller from Wootton Major. For Smith, too, enters into Faery, and even after experiencing fear and trauma and sorrow in that wide land, he finds himself unable to resist a return.

His heart was saddened as he went on his long road, and for some time he did not enter Faery again. But he could not forsake it, and when he returned his desire was still stronger to go deep into the land.

Smith of Wootton Major, by J.R.R. Tolkien

I have previously discussed Smith on this blog before. I claimed then that there was little I could say about the story, other than to delight in it and wonder at it. And in some ways, this remains true, but I think there is a little further that may be gained concerning the work and its keen awareness of how utter the desire for Faerie can be.

This, mind, despite the fact that Tolkien himself never showed any great inclination to uncover some sort of meaning or message within the work. Indeed, in response to a review of the story in which the reviewer (Roger Lancelyn Green) commented that to seek the meaning of Smith was akin to cutting open a ball in search of its bounce, Tolkien wrote:

Thank you for your most gracious review (esp. for comment on the search for source of bounce!). Though I have been much better treated than I expected. But the little tale was (of course) not intended for children! An old man’s book, already weighted with the presage of bereavement’.

Tolkien, Letter 299 to Roger Lancelyn Green

Yet upon reflection and considering the text of Smith against the letter, this claim by Tolkien seems strange. For what is there of loss and death in Smith? None of the primary characters die. Many of them end up enriched by the tale (primarily Smith and Noakes, funnily enough…yet there are few in Wootton Major who are not bettered in some way through the craft of Alf or the labour of Smith). What loss, then, is there in the story to cause sorrow? In what way does bereavement hang upon the tale?

The answer, of course, is Smith’s loss of the star, his passport to Faery. This is the great grief that is inflicted upon him – that the joys he knew for a while are not permanent (at least in this life) and that, having known them, he must lose them. And this is illustrated wonderfully clearly in the very moment when Smith departs from Faery for the last time (and even before he surrenders the star to Alf’s care).

Then he knelt, and she stooped and laid her hand on his head, and a great stillness came upon him; and he seemed to be both in the World and in Faery, and also outside them and surveying them, so that he was at once in bereavement, and in ownership, and in peace. When after a while the stillness passed he raised his head and stood up. The dawn was in the sky and the stars were pale, and the Queen was gone. Far off he heard the echo of a trumpet in the mountains. The high field where he stood was silent and empty: and he knew that his way now led back to bereavement.

Smith

Smith ends not with death or tragedy, but it undeniably ends with loss. Smith was permitted, for a time, to wander in Faery – but this licence is neither fully permissive (as he realises earlier in the work) nor his to cling on to. And though Smith does not ‘lose’ anything that was not his – his memory of Faery remains, his family flourishes and is glad, his community is blessed – nonetheless there is that loss of future hoped-for Faery. And it is a loss that stings Smith and that he resents (if only momentarily) and grieves (and the grief, I would argue, is intended to be read as being lasting).

[Alf] was looking now at the smith with friendly eyes; but he lifted his hand and with his forefinger touched the star on his brow. The gleam left his eyes, and then the smith knew that it had come from the star, and that it must have been shining brightly, but now was dimmed. He was surprised and drew away angrily.

‘Do you not think, Master Smith,’ said Alf, ‘that it is time for you to give this thing up?’

‘What is that to you, Master Cook?’ he answered. ‘And why should I do so? Isn’t it mine? It came to me, and may a man not keep things that come to him so, at the least as a remembrance?’

‘Some things. Those that are free gifts and given for remembrance. But others are not so given. They cannot belong to a man for ever, nor be treasured as heirlooms. They are lent. You have not thought, perhaps, that someone else may need this thing. But it is so. Time is pressing.’

Then the smith was troubled, for he was a generous man, and he remembered with gratitude all that the star had brought to him. ‘Then what should I do?’ he asked. ‘Should I give it to one of the Great in Faery? Should I give it to the King?’ And as he said this a hope sprang in his heart that on such an errand he might once more enter Faery.

‘You could give it to me,’ said Alf, ‘but you might find that too hard. Will you come with me to my store-room and put it back in the box where your grand-father laid it?’

Smith

Bear in mind, Smith has just returned from Faery when he suggests that he may return to Faery and surrender the star to the King. If it recalls any other passage in Tolkien for me, it seems strikingly similar to Bilbo’s repeated hopes to see the Ring once more; which is not to say that Faery is wicked as the Ring is. Rather in both cases, it is a consuming and yearning desire, and a desire that is deeply understandable…but none of this permits just satisfaction of the desire.

And so, having come to accept that he must surrender the star and do so freely, and that it is the best thing for others, Smith gives it up. But the grief is not lessened by the necessity of it, and Smith loses Faery.

[Alf] raised the lid and showed it to the smith. One small compartment was empty; the others were now filled with spices, fresh and pungent, and the smith’s eyes began to water. He put his hand to his forehead, and the star came away readily but he felt a sudden stab of pain, and tears ran down his face. Though the star shone brightly again as it lay in his hand, he could not see it, except as a blurred dazzle of light that seemed far away.

‘I cannot see clearly,’ he said. ‘You must put it in for me.’ He held out his hand, and Alf took the star and laid it in its place, and it went dark.

The smith turned away without another word and groped his way to the door.

Smith

It is a haunting, uncomfortable conclusion to Smith’s possession (or stewardship, perhaps) of the star. But as I said before, Smith has not lost anything that was his. And yet that withdrawal of Faery remains a fierce and grievous loss to him.

It is relatively common for readers to see Leaf by Niggle as being Tolkien’s personal reflection upon his unfinished Legendarium; a piece of autobiographical allegory. But, compelling though the interpretation is, there is a fairly major problem that stands in its way: the date of Leaf’s authorship and publication.

Leaf was written by Tolkien across 1938-39, when he was in the throes of working on both LOTR and The Silmarillion. Indeed, he was actively pursuing publication opportunities for both works and had Leaf published as something of a stopgap in 1945, and (though he had long barren spells of creativity) there is no indication that Tolkien intended to leave his own Great Tree unfinished during those years (though he may well have feared it would be so).

If anything, Leaf is a piece of foresight, not of summary (though undoubtedly a foresight informed by Tolkien’s everpresent niggling tendencies and occasional sustained periods without creative work). Leaf is not a piece of reflection, though it may have been a forecast of what would yet come to pass for Tolkien’s creative endeavours.

But Smith, on the other hand. Published in 1967 (just a few years before his death), and intrinsically concerned with both the joy of experiencing Faerie and the grief at losing it, Smith is deeply concerned with and aware of the possibility that a wanderer may not freely return to Faerie forever.

Tolkien continued to work and rework and revise his Middle-earth material until the end of his life. But I wonder if he knew, or at least suspected, that this was a task now beyond him when he wrote Smith. And I wonder, too, whether he keenly felt that his own Faery star was fading, or even gone.

There is no way to say for sure, of course; but given Tolkien’s brief and enigmatic comments to Green, I think it is a compelling interpretation. And it is one that is both supported by and informs the final journeys of the five hobbits in LOTR. For them, Faerie is not yet beyond reach. Like Smith and (perhaps) like Tolkien, they cannot resist the allure of returning to Faerie, having tasted of its deepest joys, but they (unlike at least Smith) are not yet barred from it, and so are privileged to return.

It is no secret that The Lord of the Rings is a fairy tale. But perhaps this is the most fairy-tale element of the entire story – the fancy that it is possible to tarry indefinitely in Faerie, the wish to return there at will as manifested by the final journeys of Frodo and Bilbo, Sam, and Merry and Pippin; all of whom escape once more into the Faerie of Valinor or Gondor ere the end – an escape that preludes and foreshadows the final Escape from the circles of the world into a true Faerie.

But in the “Eucatastrophe” we see in a brief vision that the answer may be greater – it may be a far-off gleam or echo of evangelium in the real world.

On Fairy Stories, by J.R.R. Tolkien

~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Thanks for reading – feel free to check out anything else you may be interested in on the blog, there’s plenty more to discover! Follow me on Facebook and on Twitter to stay up to date with The Blog of Mazarbul, and if you want to join in the discussion, write a comment below or send an email. Finally, if you really enjoyed the post above, you can support the blog via Paypal, and keep The Blog of Mazarbul running. Thanks for reading, and may your beards never grow thin!