It is, at long last, time to fulfil one of the promises of the Blog of Mazarbul.

Ever since I started writing this blog, I have held true to my idea that it will mostly be about Tolkien. I have veered from the course from time to time to touch on broader concepts in fiction or on specific fictional works, or even to touch on games and the arts and theology. Heck, I’ve even expanded the blog’s scope a little and given myself licence to publish a few short original works of my own on it. But there is one topic that I have never, ever touched on, despite it being near and dear to my heart, and despite it having been quoted in various sources as being a likely area of interest that I would like to cover.

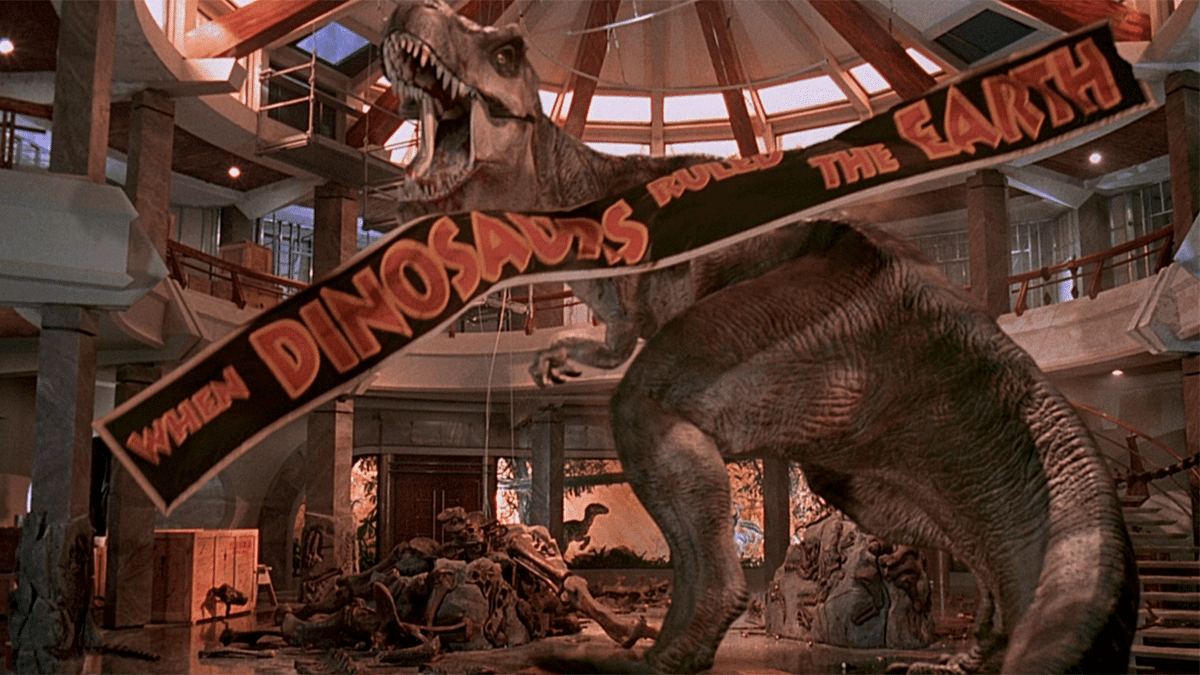

So today, I’m finally going to remedy that particular oversight. Today, I want to talk about dinosaurs.

I love dinosaurs. I have, as far as I can tell, always loved dinosaurs – there is, at any rate, no point of my life in which I can recall not loving dinosaurs. And there has not yet come a point in my life where my dinosaur love feels especially diminished

I am on record as being prepared to, if and when time travel technology to the past is invented, do anything I can to go back a good 100,000,000 years or so into the past to see as many dinosaurs as I can. I’m not much of a survivalist, and I’m hardly built for the very different climate, oxygen levels, and broad resources that would be available to me in such an absurd scenario – frankly, surviving my first day in prehistory would be an achievement and I cannot see myself getting past a week.

But I’d do it. I really wanna see a dinosaur.

To be clear, this is all perfectly insane, naturally, and I’m fully aware of it (though it doesn’t necessarily make it untrue). But I’ve been dwelling a little lately on what dinosaurs are, exactly.

Not evolutionarily, scientifically, biologically or even historically – I’m ill qualified to consider them from any single one of those perspectives. Rather, what, exactly, are dinosaurs? Especially when considered from a theological perspective?

The simple and (I think) rather facile answer is that dinosaurs ‘are’ dragons, an answer that I do not find wholly unconvincing, but it seems rather to miss the truth of the matter, too. This is a point I wish to return to, though. As for pre-existing literature on this question, that is disappointingly scarce; it would seem most modern theologians do not see our planet’s ancient reptilian overlords as being a pressing metaphysical matter.

Needless to say, I rather disagree. And while I’m quite a bad theologian, and an even worse prehistoric biologist, I rather suspect that my love for dinosaurs might actually point to something rather interesting about them. So, let’s talk about dinosaurs.

A common question (of believer and atheist alike) is why, if one believes in some sort of God, He would have created dinosaurs in the first place. After all, they lived millions of years removed from us, made in the image of God as we are. Their extinction and removal from the face of the earth, it would seem, was about as clear an act of God as one can find. And yet they themselves dominated and roamed the world for far longer than we have clung to its surface, by any measure whatsoever – we may now form the ‘dominant species’ on this planet, but chances are very good that if an alien anthropologist passed by Earth at any point along its history, it would have figured out that this is a planet of terrifying wonderful monster lizards and been on its way.

So, then, what gives? Why would God make dinosaurs in the first place?

Setting aside for a moment the fact that modern birds are indeed dinosaurs, I think there are several valid ways of approaching the question. One, of course, is to observe that the question’s preoccupation with the passage of time is an extremely limited one. God is assuredly aware of time, in the sense that He understands it – but He is not bound by it; nor is it of any especial consequence to Him.

More broadly though, I don’t know that it’s all that useful to frame the world’s creation as being for humanity. By way of what I mean, while I was considering this article, I stumbled across a fairly banal bit of bad rationalisation that argued that dinosaurs were made so that, millions of years later, we could reap the reward of their biological remains in the form of petroleum.

Now, while I do not doubt that even the internal combustion engine was conceivable to the mind of God from the beginning, it still seems an awfully selfish and extremely arrogant way of looking at the question to me. God may have made internal combustion engines possible, but He did not impose a moral imperative upon us to develop such a thing. The world was not made for humanity, in short. If anything, we were made for the world, to steward it, to dwell within it and, yes, to love it and delight in it as God does. The internal combustion engine is but an accident to all of this and irrelevant to the world’s purpose (though obviously possible to ‘be’ according to the laws of the world).

But this, then, starts to approach at why I think it is good to love dinosaurs, when we consider them from the perspective of ‘why’ the world was made. I would not dare to imagine that it is the only or best reason for their having lived and roamed the earth long before us, but it is some reason.

I mentioned before that I find the all-too-common equation of dinosaurs ‘being’ dragons to be misleading, and it is to this idea that I wish to turn to next. For it is, of course, foolish to deny that there are certain similarities between one and the other – they are at least kin in some way. And there is ample evidence of fossilised bones and materials being discovered by the ancients who imagined them to be draconic remains (and those of giants, and trolls, and all sorts of other beings marvellous and wonderful). Hence, there is a certain sense in which one can see dragons as belonging to the lineage of dinosaurs…but I prefer to think of it slightly differently. I like to think that dinosaurs have become a surprising ingredient (and occasional flavour) in The Soup.

For those who are somehow unfamiliar, the Soup is to be found in Tolkien’s essay On Fairy Stories. It is his way of expressing how story and myth arise and are to be found in marriage to and alignment with history, yet stand alone (and, importantly, can be added to and taken from). Tolkien introduces the idea by way of considering the Nordic god Thor, and critiquing the idea that Thor ‘is’ thunder.

Let us take what looks like a clear case of Olympian nature-myth: the Norse god Thórr. His name is Thunder, of which Thórr is the Norse form; and it is not difficult to interpret his hammer, Miöllnir, as lightning. Yet Thórr has (as far as our late records go) a very marked character, or personality, which cannot be found in thunder or in lightning, even though some details can, as it were, be related to these natural phenomena: for instance, his red beard, his loud voice and violent temper, his blundering and smashing strength. None the less it is asking a question without much meaning, if we inquire: Which came first, nature-allegories about personalized thunder in the mountains, splitting rocks and trees; or stories about an irascible, not very clever, redbeard farmer, of a strength beyond common measure, a person (in all but mere stature) very like the Northern farmers, the boendr by whom Thórr was chiefly beloved? To a picture of such a man Thórr may be held to have “dwindled,” or from it the god may be held to have been enlarged. But I doubt whether either view is right—not by itself, not if you insist that one of these things must precede the other. It is more reasonable to suppose that the farmer popped up in the very moment when Thunder got a voice and face; that there was a distant growl of thunder in the hills every time a story-teller heard a farmer in a rage.

On Fairy Stories, by J.R.R. Tolkien

Tolkien goes on by describing this process of blending red-bearded farmers and thunder into legend as being a consequence of their having been tossed into ‘The Pot;’ that is to say, the great and simmering blend of all matter from which Story is drawn and derived.

Speaking of the history of stories and especially of fairy-stories we may say that the Pot of Soup, the Cauldron of Story, has always been boiling, and to it have continually been added new bits, dainty and undainty. For this reason, to take a casual example, the fact that a story resembling the one known as The Goosegirl (Die Gänsemagd in Grimm) is told in the thirteenth century of Bertha Broadfoot, mother of Charlemagne, really proves nothing either way: neither that the story was (in the thirteenth century) descending from Olympus or Asgard by way of an already legendary king of old, on its way to become a Hausmärchen; nor that it was on its way up. The story is found to be widespread, unattached to the mother of Charlemagne or to any historical character. From this fact by itself we certainly cannot deduce that it is not true of Charlemagne’s mother, though that is the kind of deduction that is most frequently made from that kind of evidence. The opinion that the story is not true of Bertha Broadfoot must be founded on something else: on features in the story which the critic’s philosophy does not allow to be possible in “real life,” so that he would actually disbelieve the tale, even if it were found nowhere else; or on the existence of good historical evidence that Bertha’s actual life was quite different, so that he would disbelieve the tale, even if his philosophy allowed that it was perfectly possible in “real life.” No one, I fancy, would discredit a story that the Archbishop of Canterbury slipped on a banana skin merely because he found that a similar comic mishap had been reported of many people, and especially of elderly gentlemen of dignity. …

But what of the banana skin? Our business with it really only begins when it has been rejected by historians. It is more useful when it has been thrown away. The historian would be likely to say that the banana-skin story “became attached to the Archbishop,” as he does say on fair evidence that “the Goosegirl Märchen became attached to Bertha.” That way of putting it is harmless enough, in what is commonly known as “history.” But is it really a good description of what is going on and has gone on in the history of story-making? I do not think so. I think it would be nearer the truth to say that the Archbishop became attached to the banana skin, or that Bertha was turned into the Goosegirl. Better still: I would say that Charlemagne’s mother and the Archbishop were put into the Pot, in fact got into the Soup. They were just new bits added to the stock. A considerable honour, for in that soup were many things older, more potent, more beautiful, comic, or terrible than they were in themselves (considered simply as figures of history).

On Fairy Stories

Just that, I posit, is not only the fate but the honour of the dinosaurs – they, too, have been added to the Soup, and if in the process they have “become attached to the dragons” then it is not to the discredit of either. But I think there is something distinctly wonderful about dinosaurs being in the Soup, and it is something that deserves a little more focus.

For dinosaurs, assuredly, did live. We are able to reconstruct all sorts of interesting and verifiable facts about them, and come to many further conclusions with a fair degree of certainty. There is something tangible and precise about the dinosaur as a being of science, biology and history. And yet it remains primarily a creature of wonder.

Indeed, Tolkien himself remarks upon this in (you guessed it) On Fairy Stories:

I was introduced to zoology and palaeontology (‘for children’) quite as early as to Faërie. I saw pictures of living beasts and of true (so I was told) prehistoric animals. I liked the ‘prehistoric’ animals best: they had at least lived long ago, and hypothesis (based on somewhat slender evidence) cannot avoid a gleam of fantasy. But I did not like being told that these creatures were ‘dragons’.

Note D from On Fairy Stories

It is a pity, I think, that Tolkien fails to draw the connection between dragons and dinosaurs further than this (though it is not impossible that he discusses it further in his Lecture on Dragons, which features an extended and rather fond consideration of dinosaurs, and is a work I regrettably do not have a copy of). As mentioned above, I, too, dislike the dubious simplification that dinosaurs ‘are’ dragons or vice versa. Dinosaurs are dinosaurs and dragons must be dragons. But I do not doubt that each has acquired a taste of the other through both being present in the Soup, either. And the fact that dinosaurs belong, along with Nordic gods and banana skins, to the Soup, cannot be overstated enough.

Even the greatest and most brilliant palaeontologist or evolutionary historian has never seen a dinosaur, and likely has never guessed in full at how they actually were in ‘truth’ during life (and I am under the impression that the best such scientists are inevitably aware of that fact). There is all sorts of evidence and deductions that can be made from that evidence, yet the ever-shifting hypotheses and concepts that emerge from dinosaur studies are ample proof that we are nowhere near ‘knowing’ them.

And that, to me, is good. Which is not to say that we should not be striving to come ever closer to the truth of dinosaurs, of course. But the fact that there remains so much wonder and question about them is amazing, because in dinosaurs, we see a fascinating marriage of Primary and Secondary worlds. Real beasts, but reimagined and reinterpreted to the best of our ability.

So if dinosaurs lived on this world for a ‘purpose,’ and that purpose was in any way oriented toward humans, then it is for this, I think. Dinosaurs are, to me, a licence to wonder. A reminder that, even to the scientific and the precise mind (which are in themselves virtues) there is scope for bafflement and awe and imagination. Imagination grounded in reason and research, naturally, yet imagination nonetheless.

It is a common adult fear that Tolkien remarks upon in On Fairy Stories to be suspicious of the imagined; to brand it as being stuff for children. Yet the study of dinosaurs remains a highly serious and adult field (if one that also holds extraordinary appeal to many a child, for reasons that are hopefully at this point clear). There is nothing childlike or silly about researching dinosaurs, and the imagination of them need not be ‘fanciful,’ it can be grounded in methodical and sober facts and research.

And yet it remains imagination.

In On Fairy Stories, Tolkien describes Fantasy as being perhaps the most pure and potent form of Art over any other. In doing so, he observes this:

Fantasy, of course, starts out with an advantage: arresting strangeness.

And if ‘arresting strangeness’ does not describe the ancient alien world of the mighty, the swift, the fierce and the beautiful terrible lizards that roamed among bizarre plants across strange lands for eons unimaginable, I do not know what does. Dinosaurs were and are wonderful, and bizarre, and unimaginable and conceivable and well deserving of awe and delight and even love. It may seem strange, but I am convinced of it, and convinced that the mere happenstance of their now being extinct (again, birds aside) is no obstacle to any of this. Indeed, it is arguably an advantage of the terrible lizards, for it enhances and blends their wonder; it forms them into creatures at once of myth and of science, reminding myth-makers and scientists alike that their domains need not be wholly estranged.

Dinosaurs are, in a word, fantastic. And the nearness of that word to ‘fantasy’ is no mistake.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Thanks for reading – feel free to check out anything else you may be interested in on the blog, there’s plenty more to discover! Follow me on Facebook and on Twitter to stay up to date with The Blog of Mazarbul, and if you want to join in the discussion, write a comment below or send an email. Finally, if you really enjoyed the post above, you can support the blog via Paypal, and keep The Blog of Mazarbul running. Thanks for reading, and may your beards never grow thin!