To the elvish craft, Enchantment, Fantasy aspires…Uncorrupted, it does not seek delusion nor bewitchment and domination; it seeks shared enrichment, partners in making and delight, not slaves.

On Fairy Stories, by J.R.R. Tolkien

I’m really stuck on On Fairy Stories at the moment. I mean, if I’m honest, I’ve been thinking about OFS on some level ever since the very first time it truly made an impact on me some years back. But at the moment, it’s obviously really playing on my mind, because wherever I look, I see some fresh relevance to it in my day to day life and thought.

And as such, it only seems fitting to take OFS and apply some of its ideas to a form of story-telling that Tolkien was almost certainly unfamiliar with (at least in its modern form). For Tolkien died in 1973, one year before the publication of that now venerable RPG system called Dungeons & Dragons.

Nonetheless, I think there’s a lot of merit to considering D&D (or tabletop role-playing games more generally) through a Tolkienien perspective, and specifically through the ideas that he elucidates in On Fairy Stories. Because in the last few weeks, I’ve noticed that D&D has some really interesting congruences with Tolkien’s seminal essay. And when I say that, I’m not really talking about the ‘lore’ or the game’s rules and systems or anything like that of D&D or any other RPG system. Rather, I mean that the very act of playing D&D is a near-unique experience of Faerie, and there is (I think) an extraordinary value to the game as a result.

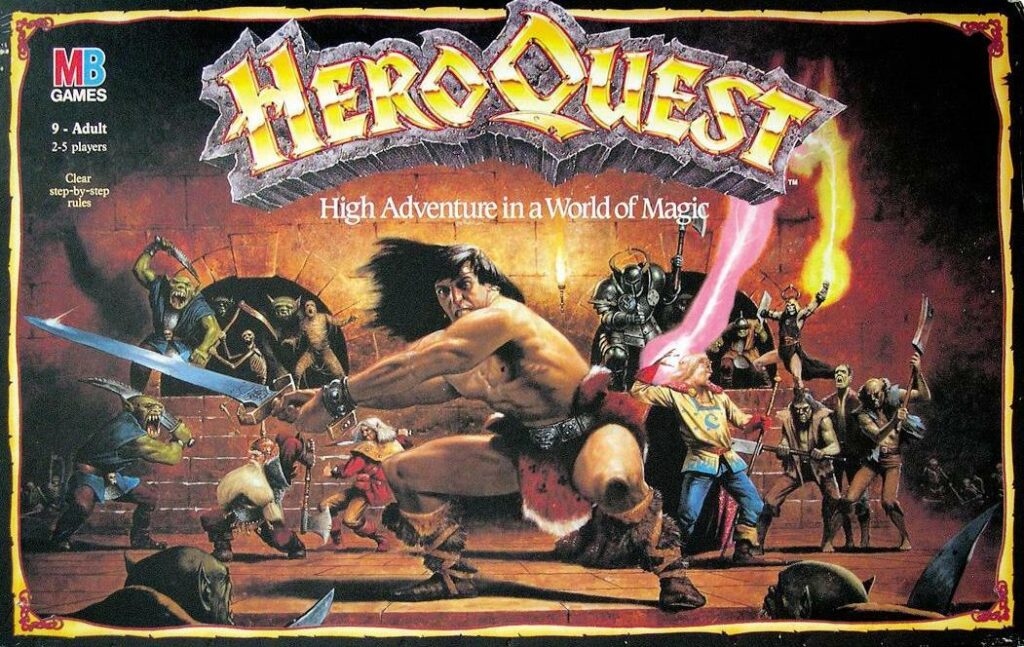

It is likely unsurprising, given my Venn diagram of interests, that I like RPGs such as Dungeons & Dragons (or to be specific, my current system of choice, Paizo’s excellent Pathfinder 2e). I’ve enjoyed them in one form or another since I was quite young – indeed, I distinctly remember game mastering for a HeroQuest group (comprised of siblings and friends) when I was about 13 years old and, upon reaching the end of the book, realising that there was nothing stopping me from…well, from just figuring out and moderating what happened next in the story. HeroQuest, I discovered, wasn’t just a box and a few miniatures and a set of scenarios. It was whatever I…no, whatever we wanted it to be.

Not only was this my first real experience of RPGs, but more importantly, it was also the first time that I realised one could take the act of realising story seriously. I spent hours and days poring over that Heroquest campaign, writing out plot notes, inventing new civilisations, conceiving dreadful foes for the party to contend with.

Growing up, I had always enjoyed playing make-believe games with family and friends, but these had always been ‘for fun,’ and were broadly concerned with inserting ourselves into the dramas and myths we all were fascinated by. HeroQuest was different. With HeroQuest, I was keenly aware that this wasn’t ‘about’ me, and that there was some sort of duty to facilitate a story (though naturally I had no ability to articulate it like that). I knew there was a responsibility that I had to ‘make’ this story, and found that responsibility compelling and exciting.

And, naturally, the story itself was utterly terrible. It was a mish-mash of any fantastical myth and world I had any conception of (i.e., mostly Tolkien, with truly irregular dashes of Warhammer and a bit of folklore). It was derivative, it was unstructured, it was implausible, and it possessed very little literary or performative or broadly artistic merit.

And yet. And yet, it was also truly magical; magical in a manner best described by On Fairy Stories.

Children are capable, of course, of literary belief, when the story-maker’s art is good enough to produce it. That state of mind has been called “willing suspension of disbelief.” But this does not seem to me a good description of what happens. What really happens is that the story- maker proves a successful “sub-creator.” He makes a Secondary World which your mind can enter. Inside it, what he relates is “true”: it accords with the laws of that world. You therefore believe it, while you are, as it were, inside. The moment disbelief arises, the spell is broken; the magic, or rather art, has failed. You are then out in the Primary World again, looking at the little abortive Secondary World from outside. If you are obliged, by kindliness or circumstance, to stay, then disbelief must be suspended (or stifled), otherwise listening and looking would become intolerable. But this suspension of disbelief is a substitute for the genuine thing, a subterfuge we use when condescending to games or make-believe, or when trying (more or less willingly) to find what virtue we can in the work of an art that has for us failed.

…

Now “Faërian Drama”—those plays which according to abundant records the elves have often presented to men—can produce Fantasy with a realism and immediacy beyond the compass of any human mechanism. As a result their usual effect (upon a man) is to go beyond Secondary Belief. If you are present at a Faërian drama you yourself are, or think that you are, bodily inside its Secondary World. The experience may be very similar to Dreaming and has (it would seem) sometimes (by men) been confounded with it. But in Faërian drama you are in a dream that some other mind is weaving, and the knowledge of that alarming fact may slip from your grasp. To experience directly a Secondary World: the potion is too strong, and you give to it Primary Belief, however marvellous the events. You are deluded—whether that is the intention of the elves (always or at any time) is another question. They at any rate are not themselves deluded. This is for them a form of Art, and distinct from Wizardry or Magic, properly so called. They do not live in it, though they can, perhaps, afford to spend more time at it than human artists can. The Primary World, Reality, of elves and men is the same, if differently valued and perceived.

On Fairy Stories

This, I think, is the enchanting potential of any RPG. To enter in and share in a shared Faerie space; to join with others in the mutual conceiving of and wandering in a Secondary World that is being sub-created before you and by you. It may be fleeting, it may be difficult to achieve, it may be tenuous. But when it strikes, it is truly extraordinary, an actual moment of Belief and Enchantment. And there is a wonderful joy in that this enchantment is not dictated but it is shared; this is no master laying down a vision. Rather, to RP is to be both storyteller and audience, with the participants being mutually swept up in their own interweaving webs of Story.

To return to my formative HeroQuest examples, it is undeniable that the Heroquest system is fairly bare for the aspiring roleplayer. It is, frankly, a fairly simple board game dressed up as a heroic RPG adventure. Yet that simplicity lends itself to approachability, too, makes Heroquest an ideal gateway into this type of story. All it takes is a few like-minded people inclined toward becoming enchanted and lo! it can weave its spell.

Further, dreadful though my teenaged story ideas were, I do distinctly remember a few early examples of being touched in this way even then. One was when the NPC that had slowly ingratiated himself with the party suddenly grew demonic wings and flew through a trapped room that the group was trying to disarm; assassinating the very nobles that the party had been tasked with saving. In hindsight, it was terribly railroaded, going against every bit of modern advice for the modern RPer. Yet the utter shock and horror on the face of every single player as I narrated their ‘friend’ soaring into the neighbouring room, and the screams and butchery that followed while they desperately tried to bypass the bewildering mechanical trap, were truly incredible.

Or for another example, take the session where the party was tasked with infiltrating the very home of Morcar, the dreaded Big Bad of HeroQuest, the villainous figure who orchestrates every misfortune and oversees every peril that the heroes encounter. I knew that this needed to be a special experience; that Morcar’s Castle needed to be set apart from the dozens of other dungeons that the party had infiltrated. So, when I drew up my planned map, I did so with the utmost care. I set it out so that it could be expansive and yet carefully directed, ever keeping the players from seeing to the end of the board, until the very last moment.

And then, when the party finally reached the far edge of the board, I stared them in the eye, and pulled from its hiding spot a second board, laying it out to connect with the first.

They went wild. To this day, I measure every GMing success I have against that moment, when my players saw the dreadful expanse of Morcar’s castle stretching before their trembling gaze.

Because they did really see it, I think, just as I had hoped that they might see it. For even then, I fully understood that my role in the game wasn’t to ‘win’ (though it was to challenge), and that the true joy of the game was in the unfolding of the story. I may not have been good at it, but whenever I managed to meet that elvish art of Enchantment, I knew that I had achieved something worthwhile.

If my players had merely been playing the ‘game;’ they would see the second map be added and simply understood that the challenge of this encounter has just escalated; that their resources (already stretched thin) would have to be managed over this coming grind. But that was not what I wanted. I wanted them to be swept away by the dread mighty of the fell location they were grimly battling their way through. I wanted them to feel the awesome power of Morcar, the unimaginable reach of his power and the true gravity of what even being in his presence entailed. And I wanted, if they did manage to achieve their goal and slip Morcar’s clutches, for them to understand that they had accomplished something near-miraculous; that their triumph was elevated by the overwhelming spectre of failure that had dogged it.

And perhaps I delude myself, but I like to think I did that by employing a little theatre and slapping a piece of coloured cardboard down on a table.

This, of course, is all that an RPG is. One can have the most elaborate props, the most carefully curated soundtrack, and a highly detailed and compelling rules system – or a sketched out map, a vague structure, and a handful of coins and paperclips representing the monsters and the heroes. In some ways, all such props are (ironically) immaterial, for the true ‘art’ is always in the story. The true art is in participating in some sort of mutual enchantment, in (to borrow a turn of phrase from Tolkien) deluding ourselves for a spell through the framework and guidelines that the rules, lore and props of any RPG offer.

When we can take green from grass, blue from heaven, and red from blood, we have already an enchanter’s power—upon one plane; and the desire to wield that power in the world external to our minds awakes. It does not follow that we shall use that power well upon any plane. We may put a deadly green upon a man’s face and produce a horror; we may make the rare and terrible blue moon to shine; or we may cause woods to spring with silver leaves and rams to wear fleeces of gold, and hot fire into the belly of the cold worm. But in such “fantasy,” as it is called, new form is made; Faerie begins; Man becomes a sub-creator.

An essential power of Faerie is thus the power of making immediately effective by the will the visions of “fantasy.” Not all are beautiful or even wholesome, not at any rate the fantasies of fallen Man. And he has stained the elves who have this power (in verity or fable) with his own stain. This aspect of “mythology” —sub-creation, rather than either representation or symbolic interpretation of the beauties and terrors of the world—is, I think, too little considered. Is that because it is seen rather in Faerie than upon Olympus? Because it is thought to belong to the “lower mythology” rather than to the “higher”?

On Fairy Stories

What truly sets an RPG apart from other such fairy tales, too, is the fact that there is a true mutuality and egalitarianism to the act of sub-creation. When writing a story or painting a picture, the creative act is always dominative to at least some extent; not merely in the domination of artist over matter but in the domination of artist attempting to influence and affect the audience. Naturally, such domination exists in an RPed story as well (as was the case with my second map in Morcar’s Castle), but there’s an extraordinary degree of interactivity and alteration in the balance of that power, too. Players will (ideally) always react as they wish their character to react, creating an unpredictability that elevates RP. And while the Game Master may have their schemes and plans and ideas, they will hopefully be taking those player-driven actions and reactions on board, allowing for a high degree of credulity, immersion, and spontaneity, and (crucially) ensuring that the GM is also permitted to enter the Faeriean drama.

This is something I’ve been reflecting on frequently with my current campaign and group of players, because they make it delightfully easy for me to be surprised and enchanted by their questions, their actions, even their motivations. I may be the architect of the world and have an undue amount of influence over the ‘story,’ as it were, but that (hopefully) is merely in aid of facilitating the actions of the party; giving them a structure and a set of ideas and themes which they are permitted to explore. And in the exploring of it, I’m frequently just as surprised at what they discover as they are.

One of my favourite passages in all of Tolkien’s assorted letters occurs when he is asked what happened to the Entwives, and answers as follows:

As for the Entwives: I do not know. … But I think in Vol. II pp. 80-811 it is plain that there would be for Ents no re-union in ‘history’ — but Ents and their wives being rational creatures would find some ‘earthly paradise’ until the end of this world: beyond which the wisdom neither of Elves nor Ents could see. Though maybe they shared the hope of Aragorn that they were ‘not bound for ever to the circles of the world and beyond them is more than memory.’…

Tolkien, Letter 338 to Fr. Douglas Carter

This answer intrigues me, in that it freely admits an authorial privilege of ignorance on Tolkien’s part that he seems to embrace. For his answer concerning the Entwives is not, ‘I haven’t decided yet,’ or, ‘I think it is better not to know.’ I do not know. And he then goes on to guess and to wonder himself, but there is a distinct and rather marvellous freedom on Tolkien’s part concerning the nature of that knowledge. Something, of course, must have happened to the Entwives. This much is self-evident. And Tolkien may have left the door open for himself to decide what precisely that something was, but as of 1972 had felt no especial need to do so.

This, of course, plays into the conceit of Tolkien not as Middle-earth’s author and (sub-)creator, but as its chronicler and discoverer. But there’s something rather more potent to my mind in that admission of ignorance, in that I think Tolkien is aware that he does not need to know. Had the fate of the Entwives become critical to the great deeds of the Fellowship and the strife of the War of the Ring, I am sure that Tolkien would have ‘found out’ what happened. But he does not know, and until there is a need to know, he was content to allow this question to remain unanswered.

All of this, I think, should seem very pertinent to D&D and its ilk, because as a semi-improvised story game, that lack of ‘needing’ to know things happens all the time; to players and GMs alike. Sometimes a player will realise something about their character that had genuinely never struck them before. And sometimes (very, very often in my case), a player will put a question to me and I will have to realise the answer.

Realise the answer, not make it up. Maybe it is disingenuous to suggest a separation between the two. But to me, there’s a very real distinction, in that the world I’ve tried to realise is just robust enough to support the emergence of detail. There are, naturally, many things in the world that my players may ask and that I would have a ready answer for, but frankly, I know nearly as little about the world as they do…my knowledge is structural rather than precise. Hence, one of the great joys of RPing for me is when the players put a question to me that I have no answer to…because that produces an answer, and allows me (and us) to know the world a little better.

For my current favourite example of this, meet Grauthor. Grauthor is a duergar, and a particularly dour and sullen example of his kind. However, he has a favourite food, and he has a particular way of viewing the world. He’s not a zealot for his kind, though he fervently believes in many of his culture’s tenets. He speaks a certain way, he goes about his work in a certain way, and he has a few qualities yet to be revealed to the party. And, from a narrative perspective, Grauthor may yet prove to be an important NPC for his knowledge of the Underdark (which has been highly reworked and adapted for my campaign to fit the larger picture; making any insights he may have doubly useful). Grauthor is, in short, a minor character, but one with some importance and certain distinguishing traits.

Oh! And there is one other thing to know about Grauthor. Grauthor did not exist before the party captured him.

Because once upon a time, Grauthor was just a nameless block of stats. A few spells, a handful of numbers, and a recommended level at which the party might encounter him. To be precise, he was this block of stats. No character, no existence, not even a physical description. He was just another token on a map for my players to sneak past or cut down on their way to discovering the outermost fringes of the Underdark. There was, in short, no Grauthor.

Until the players captured him. This much, arguably, I should’ve expected – my players love capturing NPCs. But not only did they capture him, a couple of them showed him kindness to him. They treated him gently, with respect. And thus Grauthor was born. Sullen, unimaginative, dour and more than a little morose Grauthor. And with Grauthor’s entry into existence, the party found themselves responding in kind. Some continued to be dismissive and harsh, others wondered how best to make use of Grauthor as a pawn, and some made an effort to actually help Grauthor himself; to befriend him and ease him. But all of them reacted to him in some way, and thus created further depth to their own characters.

One of my players even wrote out a really thoughtful piece considering his character’s reaction to Grauthor, and how Grauthor’s apathetic outlook and the party’s initial rough treatment of him forced a moment of genuine internal conflict and introspection. It was a sad, thoughtful, nuanced examination of a PC who has often served as comic relief, lending her a new depth for me. And it came about because of Grauthor; the duergar who was not…until, of course, he became, completely unheralded and unplanned.

And there are examples like this all over the story. In the very first session, one of my more mystically-minded players tried to communicate telepathically with an island-sized dragon turtle…I’d intended for them simply to encounter the kobolds on its back and have a moment of revelation toward the climax of the session regarding the island’s nature. But there’s now a very surprising connection between Hildegard and the dragon turtle (and a connection I’m playing the long game on) that I had no intention of forming.

A chance, fairly standard question from another player to what had previously been a fairly minor NPC about a missing master smith – “did you know him,” in short, – made me ask myself the same question. And in that moment, I knew that the answer was “yes,” and that yes has since developed into a plot I had no intention or foreknowledge of, and a plot that I’m utterly delighted by. But I never would have known that Molly knew Vulk the Smith without that question; nor would I have known many other things about Molly without the question.

And of course, every player approaches it a little differently. Yet another came to me with a fairly formed character idea, including a backstory and a history that I’d played no part in developing, but he had done so with such care and consideration of how the organisation would fit into the wider doings of the world that it was very easy to slot them in, and has further informed the operation of the broader setting. Another, who joined the campaign relatively late, wanted to play a character of high birth with political connections. I’ve had a fairly basic political plot simmering away in the background since the very beginning of the campaign, and a couple of players have asked questions related to it without engaging further. But as soon as the Wedelstein-Wawelburg family arrived, I had someone who was exploring where his character was situated within that plot, which in turn has inspired the creation of a host of characters, factions, and viewpoints.

In one sense, all of these things already ‘existed,’ in that the plot existed and necessitated people driving it. But now their details are suddenly becoming clear, as if before they had been trees depicted far away in some landscape painting that have been thrown into sharp relief by a new painting of the trees themselves, with the landscape merely hinted at around the edges. Yet there’s always some new look at the landscape, too, some new perspective unheralded and unexpected that may shimmer in the background…or, in turn, be thrown into relief by the next unplanned and unexpected player action.

And so on and so forth. Where do the uncontrolled magical powers in this orphan arise from, and what does it have to do with the death of his parents? Why would a halfling have been lost in a subterranean world – and what does this have to do with her strange relationship with time? Who is the father of the unassuming servant girl, and what business did he have straying into high elvish society? Why would Lamashtu, goddess of monsters, be interested in a kind-hearted huntress, and bestow favour upon her?

These are all questions that have, effectively, been put to me by my players, and each of them has helped me realise something fresh and new and exciting and real about the story we’re telling. And I do not think this is an atypical experience in an RPG (though its typicality does not detract from the thrill of it). Sometimes the realisations have been small things, and sometimes they’ve changed the shape of the entire story. But they’ve always been exciting for me to discover, because they inevitably reveal something further, and allow me to become a little more immersed in the unfolding of the tale with the players. Though, paradoxically, I also feel that rush of Enchantment whenever a player asks a question to which I have a clear and defined and considered answer; because those moments allow me to reveal something to them and to realise (what a wonderfully apt word) story for them.

Hence, it is truly a mutually shared Faeriean drama, and the joy of it is derived from its real-ising. Even if it is fleeting, easily broken, not often achieved, it is possible to arrive at a sensation that, for a wonderful fleeting moment, what one is doing is real. Sure, to the outside observer, I’m putting on a silly voice and twisting around comically (even as I chuck handfuls of dice and list off values and stats like some sort of demented mathematician) but, with any luck, the players really do believe that the witch before them is real, and intends to eat them, and has every chance of doing so, and thus are they able to react not just appropriately but with immersion and credulity.

The spell does not always take, of course, and it must inevitably be broken. For on a basic level, I am but marking down a tally of abstracted points until the party “wins”, based solely on how a few careless dice are tossed. But we feel and see it, every axe blow and flaming burst. We ride the elation of an unexpected success, and are crushed by the dreadful horror of an ill turn. And what form of art cannot be reduced dully to its material components? What sculpture is not a piece of chipped and graven matter, what piece of music is more than calculated vibrations perceptible only by odd little hairs in ears? So it is too with an RPed story – when one examines it from the outside, it is inevitably a dissatisfying and bemusing diversion. But to experience it from within? That is (or at least can be) an elvish Art.

And all of this experience, the ever-heightening fear and suspense and release and despair and tension and triumph and, ultimately, joy, can be in turn a fine illustration of the eucatastrophe; that term coined and described by Tolkien as being the ‘true form of fairy-tale, and its highest function.’

That, I suppose, is what I was aware of even as I plotted and schemed as the wicked Morcar in my very first and tentative steps into RP. I had no word for or real concept of ‘eucatastrophe,’ of course. And I was not afraid to kill characters; they perished frequently and tragically. The heroes of those HeroQuest campaigns suffered setbacks, trials, and failures. But always at the end of it, I knew we were working towards the happy ending, however temporary and fleeting it might prove. As the ‘villain,’ it was and is my function to provide that happy ending, and to make it truly happy. Not unearned, not cheap, not silly. But also not tedious, nor nihilistic, nor sadistic.

Tolkien describes the eucatastrophe as being a ‘sudden and miraculous grace: never to be counted on to recur,’ which may seem to fly in the face of the players being the primary agents enacting story in most RPGs. For how can their triumph be a ‘turn,’ if it is they themselves who are producing it? But the eucatastrophe does not deny agency of characters in a story (that would rather be the deus ex machina), it simply forces the spectre of catastrophe upon them unto the uttermost end. And while it is the responsibility of the GM to provide the chance of eucatastrophe, it is the duty of the players to strive towards it (as characters do in any good fairy tale); and it is the role of the dice (or whatever mechanism one uses to create chance and doubt) to actually provide the miraculous ‘turn,’ as it were.

And this, in turn, is why (I think) that element of chance is so important to this particular genre of story. Without dice, the eucatastrophe is in the hands of the GM, and hence is either inevitable or unreachable. Yet the moment that chance is introduced, so too is the possibility of disaster. And far from being a weakness of RPGs, I think this to be a potent strength. GM, players, and dice, all working together toward achieving eucatastrophe. What could be more Tolkienien?

Enchantment, discovery, and eucatastrophe. Key ingredients for the heady brew that is a fairy story, and (hopefully) all very familiar experiences to anyone who has ever played an RPG. It may seem silly or trivial, measuring this hobby against Tolkien’s seminal literary essay. Yet I think there’s worth to it. Worth in that (if such a thing is necessary) it lends support to the ideas that Tolkien explores in OFS, given how readily they can be observed in a non-literary medium such as an RPG (and, further, a medium certainly broadly unfamiliar to Tolkien himself). And on the other hand, worthwhile because it serves as a validation of the merit and worth of RPGs themselves.

To paraphrase OFS, an RPG can be carried to excess. It can be ill played, put to evil uses, and delude the minds out of which it came. But of what human thing in this fallen world is that not true? The Art of Roleplay can be every bit as compelling and rich and exciting a fantasy as any literary or theatrical work (or as tedious and badly done, naturally), and in certain respects, it is uniquely well suited for entries into Faerie’s marches. And the yearning and the enchantment and the consolation that can be experienced and fulfilled in a role-playing game can be and is a wonderfully Tolkienish experience; an experience that is described and elucidated in the great poetic companion work to On Fairy Stories: namely, Mythopoeia.

So it is, as we practice world-dominion by creative act. Wish-fulfilment we do spin and devise, to see isles from afar, and Death and victory; an endless multitude of forms appearing that we might know them and fear them and delight in them. And through the collaborative enchantment of an RPG, it is truly we who do so; as together we journey through the Perilous Realm and together uncover and experience its marvels.

Though all the crannies of the world we filled

with elves and goblins, though we dared to build

gods and their houses out of dark and light,

and sow the seed of dragons, ’twas our right

(used or misused). The right has not decayed.

We make still by the law in which were made.

Mythopoeia, by J.R.R. Tolkien

~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Thanks for reading – feel free to check out anything else you may be interested in on the blog, there’s plenty more to discover! Follow me on Facebook and on Twitter to stay up to date with The Blog of Mazarbul, and if you want to join in the discussion, write a comment below or send an email. Finally, if you really enjoyed the post above, you can support the blog via Paypal, and keep The Blog of Mazarbul running. Thanks for reading, and may your beards never grow thin!