I was flicking through the Appendices of LOTR the other day, on an unrelated mission, when something really curious caught my eye in the Dwarvish genealogy tree. It’s a really small detail, almost insignificant – but the more I thought about it, the more it intrigued me, and the more intrigued I became, the more I realised that it’s actually a whole lot of details all packaged up in a single detail.

Namely, Durin VII. When was he born? When did he reign? And, perhaps most pressingly, how did he obtain that epithet?

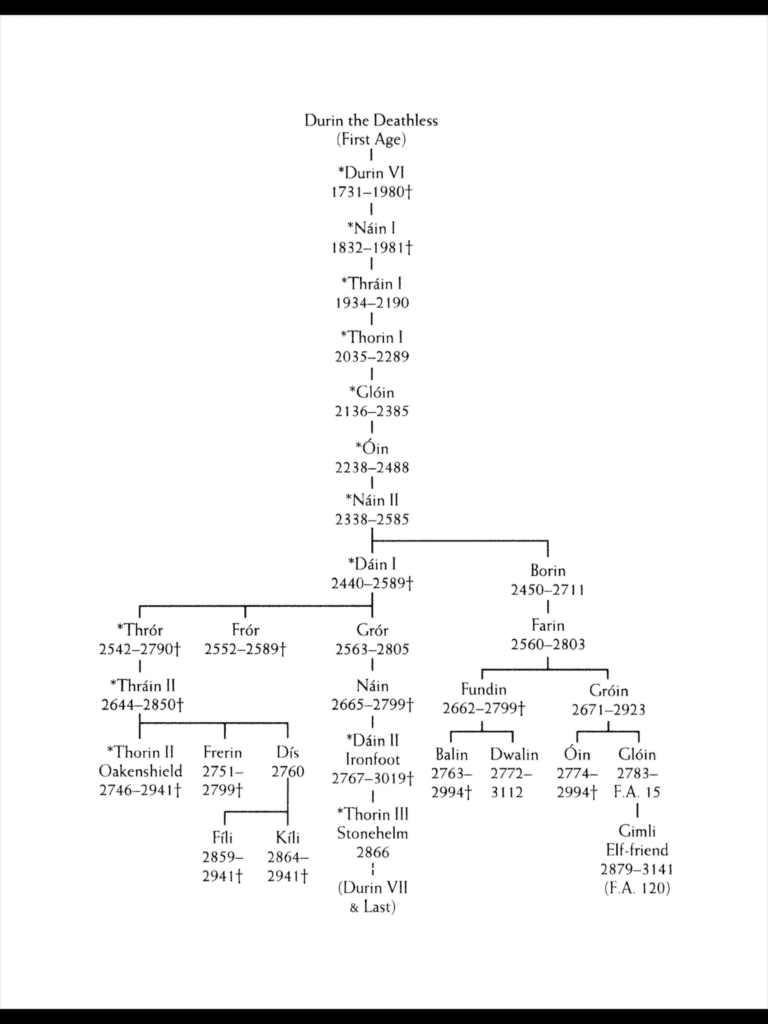

From the perspective of Tolkien as author, these are perhaps not such difficult questions. Durin VII is a descendent of Thorin III (his son in one version of the genealogical table, a version which was eventually discarded – and a version which, for reasons expanded upon below, seems unlikely to me), who lived and reigned and died at some point after the beginning of the Fourth Age. This is so because Tolkien has said it is so, and that’s fair enough.

If we consider Tolkien as translator and researcher, though, and entertain his conceit that this is a text that he has discovered and prepared for modern readers, then these questions become much more difficult. Namely, because Durin VII does not seem to have been born as of the end of Aragorn’s reign, which is more or less the final concrete date given in the Appendices. So…how on earth can he be listed as a Dwarvish King, if he is not alive then?

One answer, of course, might be that Durin the Last was added to a copy of the Red Book of Westmarch (of which there were several) at some point in the future, and Tolkien duly included it. But if this is so, why not include Durin the Last’s dates? But if the citation was made before Durin the Last, how is it known that there will be a seventh Durin…and (and perhaps much more pertinently, for those who know a little of Dwarvish beliefs), how is his epithet also known, given how, well, final it is.

For what it is worth, the text itself says of the table in Appendix A:

The Line of the Dwarves of Erebor as it was set out by Gimli Glóin’s son for King Elessar.

And this would seem to fit with the general dates given – indeed, the latest concrete date cited in the Appendices is the departure of Gimli himself, in F.A. 120, which (as known from the Tale of Years) is also the year that Aragorn died. Unless Gimli refused to set it out for Aragorn until the poor man was literally on his deathbed (which is admittedly very funny to imagine), it would seem the most likely scenario is that Gimli wrote the document for Aragorn at some point between F.A. 91 (which is when Dwalin died, erroneously written as T.A. 3112 – though I think it’s easy enough to explain as being some question of conversion between Gondorian and Dwarvish calendars) and F.A. 120. Then, at some point following Aragorn’s death and Gimli’s departure, the F.A. 120 entry date was added to Gimli (and note that Gimli has his date written in the Third Age reckoning as well, lending credence to the Dwalin theory), at least before F.A. 172, which is when the Red Book is copied to be included in the Shire’s records…the very latest date recorded in the entire story.

But none of this answers the Durin problem, it only adds to it. Because this means that it was indeed presumably Gimli who entered Durin into the genealogy, despite not even having a date of birth for him. And while it could be argued that a later scribe also annotated the text with Durin VII (as was likely the case with Gimli’s own entry), why not write his dates? And why not enter the death of his ancestor, Thorin III Stonehelm?

Because Thorin III is likely alive when Gimli departs – old, to be sure, he would be 275 in F.A. 120, but this is no impossibility for a Dwarf. And if Thorin III had died, Gimli would surely have made note of that. But by F.A. 172, Thorin III would be 327…perhaps still not an impossible age, but by all means a very great one, and it seems likelier than not that he would have died by then. And in any case, the entry for Durin VII remains undated – so either that text has not been annotated by a Gondorian scribe after Gimli, or it has…but they have still neglected to include the date, which would form a bizarre oversight.

All of this is to say that it is almost certainly Gimli who wrote “Durin VII & Last” in the table, and that Durin VII was almost certainly not king when Gimli left Middle-earth – nor would there have been any good reason to bestow such a, well, final epithet upon him. So how did this happen?

At this point, it’s probably worth mentioning that I’ve arguably buried a lead here, to a point. For any readers who are blissfully unaware, the Dwarves of Durin’s Folk held some particular beliefs regarding their original king, Durin I, ‘the Deathless’ – to put it bluntly, his title would appear (according to the Dwarves) to be very well earned indeed.

There he lived so long that he was known far and wide as Durin the Deathless. Yet in the end he died before the Elder Days had passed, and his tomb was in Khazad-dûm; but his line never failed, and five times an heir was born in his House so like to his Forefather that he received the name of Durin. He was indeed held by the Dwarves to be the Deathless that returned; for they have many strange tales and beliefs concerning themselves and their fate in the world.

The Lord of the Rings, Appendix A: III ‘Durin’s Folk’, by J.R.R. Tolkien

The Silmarillion reiterates this statement, and even makes it a little more explicit:

For they say that Aulë the Maker, whom they call Mahal, cares for them, and gathers them to Mandos in halls set apart; and that he declared to their Fathers of old that Ilúvatar will hallow them and give them a place among the Children in the End. Then their part shall be to serve Aulë and to aid him in the remaking of Arda after the Last Battle. They say also that the Seven Fathers of the Dwarves return to live again in their own kin and to bear once more their ancient names: of whom Durin was the most renowned in after ages, father of that kindred most friendly to the Elves, whose mansions were at Khazad-dûm.

The Silmarillion, ‘Of Aulë and Yavanna,’ by J.R.R. Tolkien

This question quickly becomes muddy on a number of levels. For one, it is made clear that this is an in-universe belief, that Dwarves themselves hold it to be true, rather than it being demonstrably true. Secondly, the exact mechanism by which these reincarnated Durins might manifest was something that Tolkien himself didn’t necessarily settle upon. Appendix A would seem to suggest that Durin (and the kings of the other Dwarvish kindreds) was reborn to his own descendants, a kind of periodic reincarnation, and this would seem to have been Tolkien’s initial thoughts on the matter:

For the Dwarves asserted that the spirits of the Seven Fathers of their races were from time to time reborn in their kindreds. This was notably the case in the race of the Longbeards whose ultimate forefather was called Durin, a name which was taken at intervals by one of his descendants, but by no others but those in a direct line of descent from Durin I. Durin I, eldest of the Fathers, ‘awoke’ far back in the First Age (it is supposed, soon after the awakening of Men), but in the Second Age several other Durins had appeared as Kings of the Longbeards (Anfangrim). In the Third Age Durin VI was slain by a Balrog in 1980.

The Peoples of Middle Earth, Chapter XIII, “Last Writings”, by J.R.R. Tolkien, ed. Christopher Tolkien

However, Tolkien continued to consider and develop his own view concerning the returns of Durin, moving away from ‘reincarnation’ entirely:

The matter of the Dwarves, whose traditions (so far as they became known to Elves or men) contained beliefs that appeared to allow for re-birth, may have contributed to the false notions above dealt with. But this is another matter which already has been noted in the Silmarillion. Here it may be said, however, that the reappearance, at long intervals, of the person of one of the Dwarf-fathers, in the lines of their Kings – e.g. especially Durin – is not when examined probably one of rebirth, but of the preservation of the body of a former King Durin (say) to which at intervals his spirit would return. But the relations of the Dwarves to the Valar, and especially to the Vala Aulë, are (as it seems) quite different from those of Elves and Men.

The Nature of Middle-earth, Part Two, Chapter XV, “Elvish Reincarnation,” by J.R.R. Tolkien, ed. Carl F Hostetter

So in the end, there’s no clear answer concerning the metaphysics of this Dwarvish phenomenon – reincarnation, or regeneration?

I’m personally not overly fond of the ‘regenerating’ hypothesis in NoME, because it strains at my credulity a little uncomfortably. Apart from anything else, if the bddy simply reawakens at intervals, surely that’s verifiable? The ‘reincarnation’ version at least leaves a little doubt as to whether it is truly the case, or just simply some strange Dwarvish belief – and paradoxically, though I want their belief to be ‘true’, I want it to be the same Durin each time, I don’t want to know it. But if it is indeed the same body, then that seems (to me) to strip the myth from it a little, to make it a little more concrete.

Then there are more practical questions, too. For example, what of Durin VI, perhaps best known as being the ‘Durin’ part of ‘Durin’s Bane’. Yep, that guy got killed by a freaking Balrog. Does he just, like, sleep that off? Even given a thousand years or so, somehow that stretches credulity for me. Even assuming that his body slowly regenerates, where even is that body? Because I highly doubt that his (very very warm) corpse was retrieved by the Dwarves with a damn Balrog breathing down their necks. And even if it was, where would it be kept? Erebor? Because in a few hundred years, the Lonely Mountain will have a dragon-sized problem descend upon it – and I very much doubt that Smaug was gentle in his redistribution of Erebor’s wealth. No, in all likelihood, the body of at least Durin VI would have been lost to the Dwarves…it is not impossible that they might have preserved it, but it stretches credulity.

There’s also a weird question of inheritance to consider – if Durin reawakens, what happens to the current King? Or to the heir? And if Durin weds and has children, does succession carry to them, or revert to the previous line? In a different late note, Tolkien does acknowledge this as a difficulty when reiterating the ‘regeneration’ concept, and presents a solution – but one which, ultimately, I dislike.

The Dwarves add that at that time Aule gained them also this privilege that distinguished them from Elves and Men: that the spirit of each of the Fathers (such as Durin) should, at the end of the long span of life allotted to Dwarves, fall asleep, but then lie in a tomb of his own body, at rest, and there its weariness and any hurts that had befallen it should be amended. Then after long years he should arise and take up his kingship again.(25)

25. [A note at the end of the text without indication for ‘its insertion reads:] What effect would this have on the succession? Probably this ‘return’ would only occur when by some chance or other the reigning king had no son. The Dwarves were very unprolific and this no doubt happened fairly often.

The Peoples of Middle-earth, Chapter XIII

While it’s true that Dwarves were notably unprolific, and the premise is thus easy to accept, it still rankles for me as a solution – in part, because The Hobbit presents just such an occasion, with the death of Thorin – who is succeeded not by his son, being unwed, and not by his nephews who were also slain in the battle, but by his cousin, Dáin. So on such an occasion when the reigning king died childless, a reawakened Durin would still be imposing upon the line of succession, unless by some ill chance the entire royal line were wiped out. Plus (and perhaps this is irrational, I can at least find no good reason to feel this way), this makes the line of succession of the Longbeard kings trace back not to Durin I, but to Durin VI…who is, of course, also Durin I in soul and body, but for the sake of that lineage, it means that they are no longer tracing their origin back to Durin I, through all the kings in between (Durins and no) – which is very much at odds with the family tree of Appendix A.

All in all, I personally find the reincarnation hypothesis far easier to deal with – I can only assume that Tolkien was nervous about the theological implications in his fundamentally Catholic world. He had already experimented with Elvish reincarnation and ultimately settled on an option closer to ‘rebodying’, having at first also imagined that reincarnated Elves would be reborn as infants, and I suppose he had similar doubts regarding Dwarvish reincarnation, and wanted to find a system distinct to that of the Elves. But in the end, it’s unconvincing to me, for the reasons laid out above.

Finally, and as stated above, the ‘reincarnation’ option leaves a degree of ambiguity open that I personally like – perhaps the Dwarves are mistaken, and each Durin is indeed a separate metaphysical being. But if it’s simply the exact same Durin waking up after a bit of a rest, over and over again, that’s verifiable and observable, and there wouldn’t be the same ‘some say’ element that I’m personally quite fond of.

In any case, we have once again wandered into the weeds a little – because whatever the mechanism is for Durin’s (supposed) reincarnations, we come no closer to actually solving the problem and question posed by the existence of Durin VII, save that the precedence for his coming has been established. Why is he the Last? And how does Gimli know of this?

Indeed, whether Durin VII is a reincarnated or a reawakened Durin is utterly immaterial for considering these textual questions. But there is an answer to the question, too, if a brief and cursory answer. There is actually something of an answer to this question. In The Peoples of Middle-earth, we read this:

For the Dwarves asserted that the spirits of the Seven Fathers of their races were from time to time reborn in their kindreds. This was notably the case in the race of the Longbeards whose ultimate forefather was called Durin, a name which was taken at intervals by one of his descendants, but by no others but those in a direct line of descent from Durin I. Durin I, eldest of the Fathers, ‘awoke’ far back in the First Age (it is supposed, soon after the awakening of Men), but in the Second Age several other Durins had appeared as Kings of the Longbeards (Anfangrim). In the Third Age Durin VI was slain by a Balrog in 1980. It was prophesied (by the Dwarves), when Dain Ironfoot took the kingship in Third Age 2941 (after the Battle of Five Armies), that in his direct line there would one day appear a Durin VII – but he would be the last. Of these Durins the Dwarves reported that they retained memory of their former lives as Kings, as real, and yet naturally as incomplete, as if they had been consecutive years of life in one person.

The Peoples of Middle Earth, Chapter XIII: “Last Writings”

So this, at least, answers the primary question – Durin VII was foreseen by the Dwarves (perhaps even by Dáin himself, given his words to Thráin years earlier regarding the reclaiming of Moria). The inclusion of Durin VII in the lineage is thus explained relatively easily, in the end…but several really interesting implications linger as a result.

The first is that this foretelling was apparently a matter of some confidence to the Dwarves – Gimli was clearly certain enough of its truth to include Durin the Last in the line of Kings. This in itself is curious to me, given that the Dwarves are generally not the ‘prophetic’ sort in Tolkien – yet this foretelling seems to have been considered reliable by them. I would also guess that this prophecy was at least somewhat known among the Dwarves of the time, again, given Gimli’s unconditional inclusion of Durin VII in the table.

Now, it may not seem a great matter to foretell that there will be a Durin VII – there are, after all, six instances of precedence! But specifically foretelling that he will be the last to bear that name is therefore actually quite a big deal. Further, this prophecy is a recent one – it is explicitly stated that it was made upon Dáin’s accession to the throne, not earlier. And there is no mention of any such ‘limitation’ on the number of Durins in any other text concerning the rebirth/return of the Dwarvish Fathers. In other words, this prophecy is reliable, recent, and ultimately ruinous to the Dwarves at the turn of the Fourth Age.

Because though it is not explicitly stated, this prophecy does at least hint toward the failing and end of the Dwarves as a people, too. Like I said, there’s no reason to believe that there cannot be a Durin VIII, no sort of metaphysical rule imposed upon how many times he can return. So, at least one likely conclusion that the Dwarves could draw would be that there will be no Durin VIII, because there will be no Longbeards by such a time…and they might be right to draw that conclusion, given an early version of Appendix A:

And the line of Dain prospered, and the wealth and renown of the kingship was renewed, until there arose again for the last time an heir of that House that bore the name of Durin, and he returned to Moria; and there was light again in deep places, and the ringing of hammers and the harping of harps, until the world grew old and the Dwarves failed and the days of Durin’s race were ended.

The Peoples of Middle Earth, Chapter IX: “The Making of Appendix A : (iv) Durin’s Folk”

Though no such explicit description of the end of the Dwarves appears in the final Appendices, there are enough hints concerning their diminishment as the dominion of Men waxes to assume that they did indeed fail. And, tragically, the Dwarves have foreseen that failure – they know, or at least must be wondering and guessing, that their time is drawing to an end (if that end be hundreds or even thousands of years away) during the War of the Ring.

The Third Age came to its end in the War of the Ring, but the Fourth Age was not held to have begun until Master Elrond departed, and the time was come for the dominion of Men and the decline of all other ‘speaking-peoples’ in Middle-earth.

LOTR, Appendix B, ‘The Tale of Years’

It’s a lot of little details and hooks, but it paints a really tantalising picture for me – the idea that the Dwarves are aware that they, as a race, are doomed to diminish and fail. So much of the Legendarium is concerned with those themes, of course – but it’s not dwelt on with the Dwarves, though arguably theirs is the greatest loss. Men, too, are diminishing, but if they will fail altogether is beyond foresight – and though the Elves will fail in Middle-earth, still their people live in Valinor. The Dwarves have no such consolation – yet, of course, they persist, they continue to do what they can, and (arguably) with less angst than that of Elves and Men.

And that’s the beauty and tragedy of the Dwarves, really – they persist and endure because they were made to be hardy, to be steadfast, by Aulë. Yet they will not endure so long as Men will, because it is the fate of Men to inherit Middle-earth – just as how the Dwarves were first-made of the people of the world in Aulë’s impatience, yet were not permitted to awaken before the Elves, because that was the fate of the Eldar.

This blog isn’t exclusively Dwarf-oriented, of course – but I’ve always had a really soft spot for the Dwarves, and I think this is part of the reason why. Because there’s something beautiful and noble in their tenacity – in a way, they’ve always been doomed to second place, yet they persist, and achieve things of great beauty and worth and merit in their persistence. Even towards the end of the Third Age, as they become aware that their time is drawing to a close, they persist, for no other reason than that it’s right to do so…fighting, as Tom Shippey would put it, the long defeat. Perhaps even (in my eyes at least) encapsulating that long defeat.

They’re not given as much credit as I think they’re due, Tolkien’s Dwarves. And though it takes a bit of extrapolation to get there, I do think there’s something really notable about their prophecy of Durin the Last, and what it reveals of their race. I once (jokingly) argued that there was a hidden story concerning Gimli in LOTR – but actually, there is. And it’s a sad, and noble, and heroic story of triumph and failure – a very Dwarvish story, really.

The world is grey, the mountains old,

The forge’s fire is ashen-cold;

No harp is wrung, no hammer falls:

The darkness dwells in Durin’s halls;

The shadow lies upon his tomb

In Moria, in Khazad-dûm.

But still the sunken stars appear

In dark and windless Mirrormere;

There lies his crown in water deep,

Till Durin wakes again from sleep.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Thanks for reading – feel free to check out anything else you may be interested in on the blog, there’s plenty more to discover! Follow me on Facebook and on Twitter to stay up to date with The Blog of Mazarbul, and if you want to join in the discussion, write a comment below or send an email. Finally, if you really enjoyed the post above, you can support the blog via Paypal, and keep The Blog of Mazarbul running. Thanks for reading, and may your beards never grow thin!